Contents

Kin-groups

The kin-group continued to be the basic social institution of most societies into this era, with slavery and fosterage being commonly practiced as before. Some differences had probably started emerging between Goidelic and Brythonic customs, however. Unlike Gaelic practice, for example, Welsh foster-children could inherit land from their foster-parents. In both cases, the bonds lasted for life, for foster-children were to help support their foster-parents in their old age.

Kings and Kingdoms

This era clearly was a formative one for the development of kingship in the Insular Celtic world. Although those regions with contact with the Roman world were particularly likely to be stimulated in this evolution of the accumulation of power and authority, this was not always the case (Brittany probably being the most in contact and least developed) and there is a common core of Celtic terms and concepts which recur across these kingdoms.

Kingship had, by necessity, a very strong military dimension: kings had to be effective warlords, securing territories for their people and acquiring goods and lands with which they awarded their loyal followers.

All early medieval rulers needed to be military leaders, which is one reason why the rulership of minors and women was extremely rare. The formation of kingdoms in post-Roman Britain was founded on the ability of their leaders to exploit the Roman failure to maintain the borders of Britain and the seas around it. (Yorke, “Kings”)

As a general rule, kingship in the ancient Celtic world, as in much of the rest of the ancient world, was a highly local and ritualized affair. Celtic kings were resistant to having their realms absorbed into the domains of other rulers and the harsh terrain of many of the Celtic medieval communities which were difficult for travel and communication aided in the prolonged independence of many of these rulers.

Despite this, overlordship – lesser kings who were the subject of another, more powerful king – was recognized and practiced by this era. Subject kings had to pay tribute to their overlord, provide military services to him, and give him (and his retinue) hospitality. The overlord in turn protected the subject king and his people but, at least in theory, did not have any authority or power inside of any kingdoms not his own. These arrangements of subject and overlord usually dissolved as soon as either one of them died, leaving the successors to make new arrangements.

Class Discussion

How is overlordship visible in the account of St. Columba in the Pictish court in Adomnán, Vita sancti Columbae §2.42?

Christianity

Whereas the pagan religions of the ancient expect the existence a multiplicity of gods and ritual behaviour, according to place, occasion and personal preference, the god of Christianity is a jealous god whose followers do not embrace any such diversity.

The unique force of Christianity, and its distinctive feature in the period of conversion, was that it denied the character of a god to all other divine powers; it destroyed belief in the old gods while it created belief in the one Christian God. By contrast with pre-Christian cults, which allowed equal rights for all to believe anything about any number of deities and to pay equal respect to all of them as long as none was hostile or aggressive to other beliefs, the Christian God showed no such tolerance but was constantly at war with all rivals.

The earliest evidence indicates that druids were of the élite class and were intimately involved in the exercise of power in the Celtic world. The introduction of Christianity posed a direct threat to their monopoly on power where they still existed (Ireland and parts of Scotland). Thus, Christianity and druidism were fiercely opposed to one another from their first encounter.

Christianity had different messages for different points of the social spectrum. Those who were the most weak and vulnerable in society, especially women and the lower classes, would have welcomed its message of compassion and equality (something noted by opponents of Christianity). The church could make the most leverage out of the conversion of élites, even if commitment to orthodoxy was superficial initially, for this brought patronage (especially access to land), respectability, and the nominal allegiance of their followers. Reforming the complex fabric of secular culture – people’s actual habits, practices, and values – was a much more difficult and protracted affair.

However it worked, it worked well: the number of Christians went from about half a million in the 2nd century to about five million by the end of the 5th century, with growth accelerating towards the end of that period.

Christianity was imbued with many aspects of Roman civilization – not least the Latin language itself – and offered advantages to the élite based on these imperial associations: networks with the rest of the Romanized world, international prestige, and the new technologies of literacy.

During their own lifetimes, the early church leaders (some of whom would be later memorialized as saints) were generally uncompromising reformers of secular society, confronting practices and values which they saw as incompatible with Christianity. Later, when paganism was a spent force, they could be depicted in a soft light as gentle and amiable compromisers. This is a common pattern we can see in the Celtic world and elsewhere, even in the medieval period: things that were repressed in the past could be romanticized nostalgically once they no longer posed a threat and the hard edge could be taken off the portrayal of earlier Christian reformers.

On the other hand, Christianity inevitably takes on features of local culture wherever it goes and must represent itself in terms that its host culture can understand (especially when such features do not contradict the essentials of Christianity and conversion is a matter of choice and not force). “The culture engaged in becoming dominant, in this case the culture of the early European Christian Church, had both to make concessions and invent attractions if its aims were to be fulfilled.” In a letter to the Pope c.604 the Irish missionary Columbanus, based in Luxeuil, asserted the “the one hundred and fifty authorities of the council of Constantinople, who determined that churches of God established among pagan barbarians should live according to their own laws as they had been taught by their fathers.” This was one of a number of precedents allowing local custom to survive the transition to Christianity, especially after explicitly pagan elements were expurgated.

Class Discussion

What strategies of conversion appear in the traditions recorded about Saint Patrick in the Tíreachan’s Collectanea §26? How does this passage reflect some awareness of pagan tradition? How do the daughters expect the Christian god’s status to be manifest?

In what ways do the Statutes of the Synod of the Bishops attempt to control the actions and movements of the clergy in the church in Ireland? How do they attempt to monopolize power and authority for Christianity and degrade pagans?

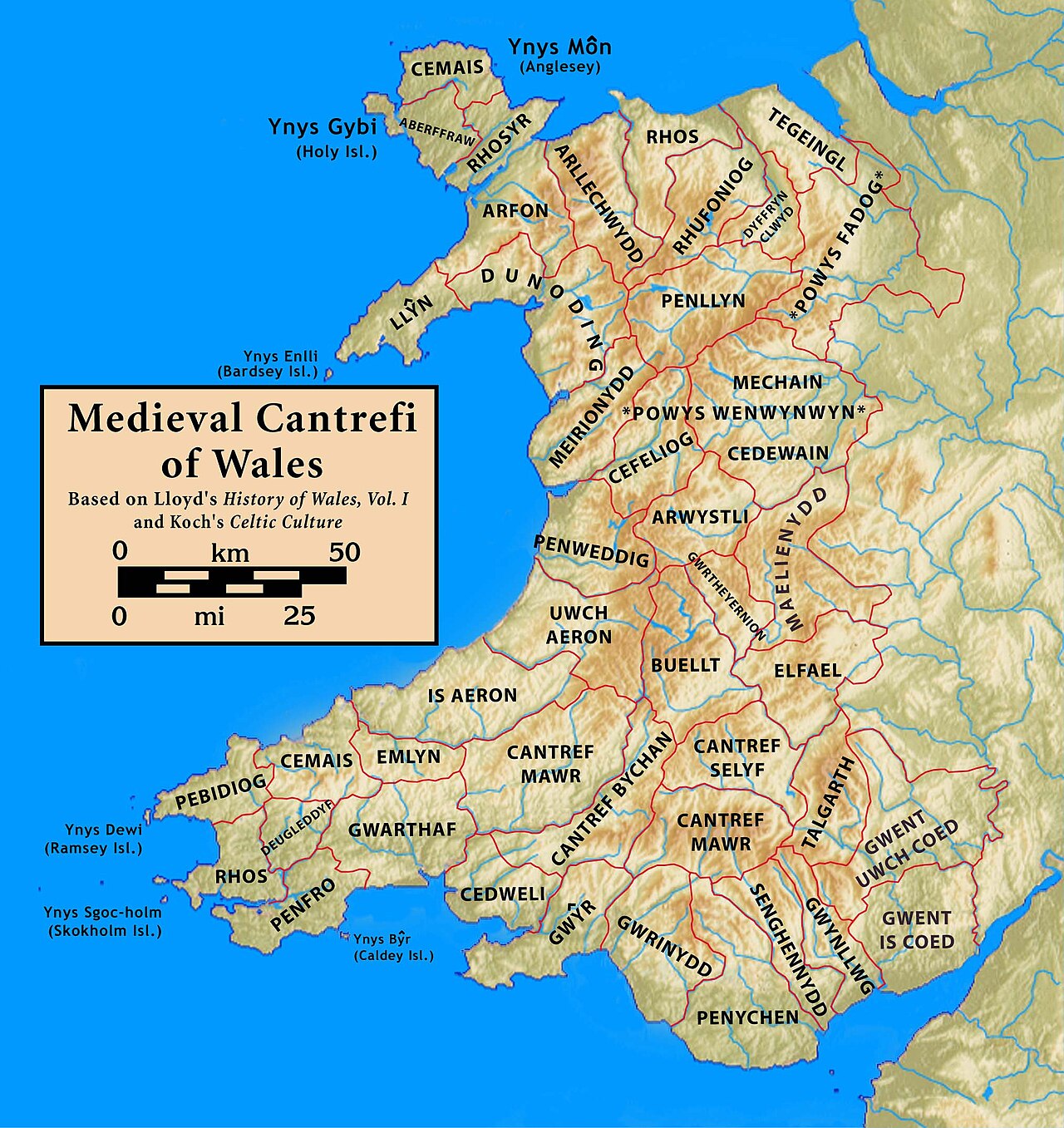

Britons

The tref “homestead, estate” was the basic unit of Brythonic local life. One hundred trefs was called a cantref. A cantref was essentially an independent kingdom: each had its own ruler, royal residence (llys), and court for dispensing justice when the nobles were gathered. Each cantref was also divided into two or three administrative units, each called a cwmwd (pl. cymydau, often called “commote” in English). Each cwmwd was to have a maerdref “mayoral farm” where the king and his retinue would stay when they visited the cwmwd. The tenants on the farm were responsible for the upkeep of the buildings and for the production of food on the estate.

That this system is derived from earlier Celtic patterns, and not just an innovation of Welsh or Brythonic society, is suggested by the fact that an equivalent system is recorded in early Gaelic Scotland, where the term cét treb corresponds exactly to cantref. Although there are early references to some of the cantrefs of Wales, no complete list of them survives until the 15th century.

The surviving Welsh law texts have conflicting definitions of the llys but it seems to have contained nine buildings constructed by unfree servants, including a royal hall, bed chamber, kitchen and toilet. Most of these were separate, free-standing buildings.

Place name and archaeological evidence suggests that settlement in early Cornwall, like Wales, consisted of estates (tref). Groupings of these estates (called “multiple estates”) had their own religious centres and noble court (llys), and there was probably also the larger division of the cantref.

Unsurprisingly, similar practices and patterns seem to have been dominant in Brittany. The peninsula was fragmented into a number of independent kingdoms until the early ninth century.

Our earliest records imply the existence of the war-band (teulu, “comitatus”) accompanying Brythonic leaders. Gildas’s condemnation of Maelgwn (in On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain §33) describes the “young lions” that helped him overthrow his uncle, and the early Brittonic poem Y Gododdin contains elaborate descriptions of the entertainment of the war-band in the hall of the ruler before they departed for war and glory.

Names are one important way in which a commitment to Christianity was expressed in medieval societies. Names from the Old Testament (such as Selyf from Solomon, Sawel from Samuel, and Iago from Jacob) seem to have been popular in the sixth century amongst the British élite, at least in Wales.

The British church (that is, the Christian church inherited and run by native Britons within and for their own communities) must have helped to foster a sense of British identity and cultural cohesion across Brittonic territory. Gildas, one of the few Britons whose voice reaches us from the sixth century, writes of Britain as the territory of a single people, even if it was ruled in discrete kingdoms. The structure and operation of the British Church also facilitated this ethnic solidarity: synods were convened whenever important matters were to be resolved and ecclesiastical scholars participated in such decisions along with bishops. The ethnic significance of the British Church might also be inferred from the allegiance of the Britons in Armorica to their own religious institutions and leaders and their resistance to the efforts of other church centres to claim authority over them.

The career of Macliau illustrates that the church in Brittany could be used to enhance and reinforce secular power. After escaping from the machinations of his brother and rival, Canao, Macliau became the bishop of Vannes. He then went on to become king of Vannes when Canao died c.570.

Although the wanderings of Irish monks on the continent are well known, the perambulations of Christian Britons, who accompanied and even preceded their Irish equivalents, are less well advertised. Besides the many British clergymen who accompanied or came to work among their kin in Brittany, there were even churches for Britons living in Galicia (in north-west Spain) with their own British bishop in the 560s and 570s.

Gaeldom

Leadership

The basic political unit of early Ireland was called the tuath (pl. tuatha). Every tuath was an independent, self-governing entity with its own king (rí) and political, legal, and religious apparatus. As one proverb stated, “A tuath without a scholar, church, poet or king (who negotiates contracts with other tuaths) is not a tuath.” There were probably between 100 and 150 tuatha in Ireland in this period.

Early Irish kings could only exercise their powers within their own tuath. There were hierarchical arrangement of kingship: an overking (ruiri) was king over 3 or 4 kings; the king of overkings (rí ruireach) usually governed at the level of the province. Subject kings paid a tribute to their overlord, but he was not allowed (according to the letter of the law) to interfere directly in the internal affairs of any but his own tuath. Each king could create treaties of friendship with other kings (cairde), or alliances (cor) pledging loyalty on behalf of people.

According to the early Irish law tract “The Five Paths to Judgment,” there were several requirements for kingship. He must:

- be the son and grandson of a king;

- be free of criminal charges;

- not be guilty of theft;

- be physically fit and handsome;

- possess three estates, each with 20 cows and 20 sheep.

Not only did a candidate have to meet these requirements, but the current king could be deposed if he broke any of them. The expulsion of kings who break one of these rules is a common theme in early Gaelic literature and the historical record. Once put in office, an additional estate within the tuath was granted to him to give him the resources to carry out his duties, including the upkeep of his main officials. Land had to be parceled out to the poet, judge, medic, historian, and other members of his retinue.

The king had to ensure that his residence was a place of protection, free from wanton violence. The king could take people into his protection: aristocrats often targeted their rivals for assassination. Even churchmen were not above this kind of foul play. The king had to defend outsiders (non-members of his tuath) while they were in his realm, guaranteeing passage unharmed by those in his own kingdom.

Another crucial concept in the exercise of power in the Gaelic world (which has echoes in Welsh tradition) is that of fír flathemon “the ruler’s truth.” This belief, which had legal, political and religious connotations, asserted that the success of a king’s reign and kingdom – even the soil and climate – depended on his ability to maintain truth. The origins of this belief clearly lie in the sacred, pre-Christian role of the king and kingship, and his relationship with the divine powers, even if it was easily absorbed into Christian codes of conduct.

By the 7th century Irish scholars began to compose manuals for kings instructing them how to be a good and effective ruler. These textbooks, whose genre is called in Latin Specula Principum “Mirror of Princes,” became very important texts in medieval Europe and it is clear that these early Gaelic tracts had a strong influence on the development of the genre on the European continent.

According to his biographer Adomnán, Columba presided over the inauguration of Áedán mac Gabráin. If this claim is true and not just church propaganda, it would be the first Christian ordination of a king in Europe. In any case, it indicates an early recognition of the ties between religious and secular authority. Áedán’s intention may have been to create ties to Columba’s kindred in Ireland; Adomnán, on the other hand, was promoting the ideals of Christian kingship and the right of the church to be involved in the affairs of state. While there were many other missionaries in Scotland during the Age of the Saints, few were as influential as Columba and his successors. The figure of Columba continued to play a role in the inauguration of Scottish kings until the thirteenth century.

Class Discussion

What does Críth Gablach “Branched Purchase” § 105, 119-21, 123, 129 say about the rights and responsibilities of rulers, and about the relationship between ríg “king” and tuath “kingdom”?

Fian Bands

When the son of a nobleman came of age at fourteen or seventeen, he was presented with a spear (gae) and shield (scíath), representing his coming of age as a warrior. In fact, the common Gaelic term for warrior is a compound of these two terms (gaiscech). It might have taken several more years before this son could inherit land and settle down on it; in the interim period, he joined a band of other young, unsettled warriors, called a díberg or fían (usually translated as “brigands” in modern English). These two terms appear interchangeably in early sources, with members of such bands referred to collectively as maic báis “sons of death.”

Bands of brigands were made up of two kinds of members: élites (mostly male) who had not yet become members of the settled community, and men for whom brigandage was a chosen occupation. Gangs of warrior-hunters lived outside of the geographical bounds and social norms of conventional society, often preying on the settled community and, later, monasteries. The díberg and fían appear to be orders derived from older Indo-European “wolf cults” in which warriors fostered a close symbolic association with wolves. Terms such as mac-tíre could be equally applied to warriors and wolves, and brigands were said to assume the appearance or behaviour of wolves.

The church saw such practices as violent and aberrant, especially as they threatened the members and property of the church itself. It thus classed druids, satirists and brigands together as enemies of the church and attempted to minimize their access to legal redress and economic resources. The early lives of the saints portray them getting the upper hand on brigands and sometimes even converting them to the new faith. A scenario of this nature can be found in Muirchú’s Vita sancti Patricii §1.23, where a brigand accosts St. Patrick but is converted to become a missionary on the Isle of Man.

Hostels

Professional hostel keepers were supported by kings in order to provide food and shelter for those traveling, who by definition would be of the élite class. According to the tale Bruidhean Da Choca “Da Choca’s Hostel,” hostels were set up at crossroads (“the meeting of four roads”); guests were assigned food according to their rank and were allowed to take the meat from one thrust of the fleshfork into the cauldron which kept meat boiling.

Christian Conversion

Linguistic evidence suggests that the way in which Gaels adopted and adapted Christianity into their society may have been fairly unusual for this period. In many societies undergoing conversion to Christianity, there is a sudden and widespread appearance of names from the Bible amongst the new believers. To the contrary in Gaeldom, most of the early Christian élite kept their names and naming patterns. This suggests that Christianity did not disrupt some fundamental sense of their connection to their pagan ancestors and the identity that enjoyed before conversion and that the process of Christianization was gradual.

Furthermore, many native Gaelic words were used to express concepts and practices within the church, rather than requiring a sudden and complete importation of Latin terminology. Words like dia “God,” cretem “belief,” noíb “sacred,” and crábud “piety” were Gaelic words predating Christianity used in the early church and are still in use today. Although the 7-day week (originating in the Jewish calendar) was brought with Christianity, the previous time reckoning system, based on the lunar calendar and consisting of 3-, 5-, 10- and 15-day periods of time, survived into the early period of the church.

The Tullahennel brooch (above) was discovered in 2009 when a woman in North Kerry, Ireland, was clearing out the ashes in her peat fire and found the brooch in her fireplace grill (the brooch had been embedded in the peat she burnt). The brooch seems to date from c. 600 CE (judging by its style). Although it is a typical brooch worn by the élite of the period, it is particularly interesting in that it contains explicit Christian symbols: the Greek symbols Chi and Ro, the first two letters of “Christ.” Wearing such a brooch would have both asserted the wearer’s noble status and his Christian identity.

Architecture

After the departure of Roman forces, most of the people in Britain had essentially reverted to the settlement patterns and domestic architecture of the Iron Age. Houses, like other buildings of the early period, including churches, were generally constructed of timber. The walls were constructed of a double-layer of wattle and daub. The sharp ends of the wattles had to be pointed inwards; in early Irish law, visitors could sue their hosts if they were injured by them! Houses seem to generally have had two doorways on opposite sides of the walls, closed with wickerwork doors. An Irish king’s residence would have a protective stone wall around the perimeter, built by the king’s clients.

Two forms of defensive settlement sites emerged and proliferated during this period in Ireland: the ringfort (ráth) and crannog (artificial island).

The ringfort (see above) was enclosed by a circular dry-stone wall two metres or more high; this was usually made more imposing and difficult to assail by one or more ditches dug around its outer wall. Although about 80% of ringforts are between 20 and 50 metres in diameter, with a single encircling ditch, a few are up to 110 metres in diameter and are protected by two or three enclosing ditches. About 45,000 original ringforts have been identified in Ireland; remains of several thousand still of them can still be seen in the countryside. Muirchú’s Vita sancti Patricii (§1.25) contains an anecdote mentioning the building of a ringfort.

Reconstructed crannog on Loch Tay

There is also a long history of crannogs in both Scotland and Ireland. As there are debates between archaeologists about the exact definition of a crannog, there are conflicting ideas about the time or place in which this type of settlement originated; for the purposes of this discussion, we can consider them to be islands created with a layer of timber beams rammed into a lakebed and built up further with other materials (rocks, brushwood, debris, etc).

The importance of water and watery places as gateways into the Otherworld, where offerings could be made, probably helped to stimulate the creation of the crannog. Indeed, people intentionally chose to create crannogs rather than to occupy similar natural features.

Some scholars believe that crannogs were invented in Scotland and imported later into Ireland. Although there is some evidence of crannogs (or crannog-like structures) as early as the Neolithic in Scotland, the majority of timber tested gives dates of 1,000 BCE to 500 CE. This, of course, is the period in which some scholars place the Celticization of the British Isles, the Late Bronze Age through the Iron Age. About 370 crannogs have been identified to date in Scotland (see map below), but it is certain that there are many more which have not yet been located. Crannogs are primarily found in the west of Scotland, especially in Argyll and the south-west.

Over 2,000 crannogs have been identified in Ireland (see map below), most of them probably associated with high social rank. Although the building of these defensive sites stopped after the 10th century, they continued to be used and occupied as late as the 18th century (in both Ireland and Scotland).

Two or three houses could be built in a ringfort or crannog, enough space to house an extended family and slaves.35 The size of a house (and defensive structure) was directly related to the status of its owner, although the homes of kings and chieftains were made of the same materials and by the same techniques as those of the ordinary (free) population; indeed, élite homes are difficult to trace in the archaeological record. Virtually no buildings in this era were meant to be permanent structures, but were periodically rebuilt from local materials.

The dominance of these settlement types (ringforts and crannogs) in the early medieval period must be directly related to the growing power of the élite: these sites were undoubtedly designed to enable them to be defended against attackers, who hoped to get some of the accumulating wealth of the owners (especially in form of cattle) which they were collecting from their clients and dependents. Many of these defensive sites were built near fields cultivated for agriculture. These sites were not just defensive in nature, but also displayed the new power and status of the élite. Excavations conducted at a small selection of ring-forts and crannogs have revealed imported luxury goods and metal-working sites.

The geographical distribution of housing within any particular tuath also seems to correlated to status in early medieval Ireland: the middle-ranks probably occupied the inland area of the territory, while the highest ranks were close to the boundaries and were surrounded by the low- status dependents, who provided agricultural labour and helped to protect the territory against incoming enemies.

Class Discussion

What does Vita sanctae Brigitae Chapter 30.2 tell us about how large construction projects were accomplished and the work allocated?

References

Bannerman, “The King’s Poet.”

Carey, A Single Ray.

Crawford, “Settlement.”

Fleming, “Lords.”

Flint, The Rise of Magic.

Henderson, “Taking the waters.”

Jones, “Llys.”

Koch, Celtic Culture.

— “Why was Welsh.”

McCone, Pagan Past.

Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland.

Preston-Jones and Rose, “Medieval Cornwall.”

Simms, “Gaelic Military History.”

Smith, Province.

Stafford, “Kings.”

Thornton, “Communities and Kinship.”

West, “Aspects of díberg.”

Yorke, “Kings.”