Wales

By the time of Henry Tudor’s death in 1509, Wales had been integrated further into the English state at the expense of cultural autonomy. The Marcher Lords continued to abuse their powers without much accountability, and the governance of Wales as a whole was marred by an inadequate enforcement of law and authority.

The next king of England, his son Henry VIII, broke his allegiance to the church of Rome in a series of measures from 1532 to 1534 and made himself the head of the (Anglican) Church, setting the English Reformation into motion. Henry began to dissolve church properties and annex them to his own.

The Welsh did not instigate an internal reformation of the church due to any frustration or disapproval of the status quo; it was, rather, another measure imposed by the English king for his own political aims. All 47 monasteries in Wales were dissolved and many holy relics were destroyed by the king’s agents. Despite much bitterness, the Welsh did not demonstrate any overt resistance to these actions.

Still, there was a large chasm between pledging loyalty to the king as head of church and state, as required by law, and actually integrating the full implications of Protestantism into Welsh life and belief. The Reformation in Wales is thus best seen as a protracted series of changes that began in 1536 but continued into the late eighteenth century.

In 1534, fears that France and Spain might form an alliance and lead a crusade against heretics, including King Henry VIII. Rowland Lee, the bishop of Lichfield, expected that the invasion force would land on the Welsh coast and went to great lengths to overhaul the military garrisons around Wales and keep the populace cowed into submission. Although, in fact, effective large-scale leadership amongst the local élite was quite limited – even those descended from the old Marcher Lords had dwindled in number – the political tensions provided the excuse for tightening the noose around Wales and the Welsh.

Union with England

Assimilating Wales into the English state was an aspect of the larger enterprise of unifying the realms claimed by the English Crown: the imposition of a single set of political, cultural, economic and linguistic norms across the kingdom. The English expressed great hostility to Welsh culture and language, and the authorities saw it as their calling to reduce Wales to “civility” and obedience. The English bishop of St Davids, William Barlow, for example, petitioned that an English school be established in the diocese in which “Welsh rudeness would soon be framed to English civility and their corrupt capacities easily reformed with godly intelligence.”

Thomas Cromwell was the leader of efforts to anglicize Wales and “unify” it with England; he saw the country as a potential threat, given that England’s enemies could land on its extensive shoreline and the Marcher Lords could be defiant to the authority of the English king. Cromwell set parliamentary statutes into motion in the 1530s to achieve these ends, particularly the Act of Union (1536).

The integration of Wales into England appealed to many of the Welsh gentry who saw opportunities for their own advancement by aligning themselves with the English Crown. Indeed, the English authorities attempted to ensure the success of the unification of England and Wales by winning the loyalty of the Welsh gentry.

Although not all proved willing and obedient subjects, enough of them were invested in the Tudor dynasty and eager the earn the rewards offered by filling the ranks of administrative office that long-term integration was secured. By the mid-17th century, many of these landed families had come to extend their power and wealth by demonstrating their ability to act as agents of the English Crown, albeit by distancing themselves from the Welsh language and culture, and their lower-status Welsh compatriots.

The 1536 Act of Union had other unanticipated effects, however: the removal of distinctions between “Welsh” Wales and the old Anglo-Norman regions of the Marcher Lords helped to reunify Wales cultural and linguistically, allowing the Welsh to regain a sense of national territory. Most towns developed a stronger Welsh character and the Welsh language made further inroads, even though a few of the urban areas retained their sense of Englishness. The Welsh term iaith means both “territory” and “language,” reflecting this strong sense of connection between these two concepts in Welsh identity.

Scotland

Clan Donald’s adversaries gained from the forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles. Archibald Campbell, the second Earl of Argyll, was appointed lieutenant of the former territory of the Lords of the Isles in 1500, and from 1514 to 1633 the office of Justice General (the chief judge in the Scottish criminal court) was inherited by successive Campbells of Argyll. Gordon of Huntly’s estates were extended into the upper Spey Valley and into Lochaber in the 1500s, where he came into frequent dispute with Clan Chattan and the Mackintoshes, who had held their lands under Clan Donald. Meanwhile, disaffected Hebrideans began migrating to Antrim, spilling into neighbouring regions and consolidating the control of Clann Eòin Mhóir.

The powers invested in agents of the Scottish Crown in the Highlands were blatantly abused, either with the tacit approval or neglect of king and his council. The Crown freely exercised its powers of eviction, thereby adding to social disruption and the number of “broken” (landless) men resorting to mercenary activity. The way in which the central government executed its system of justice in the Highlands encouraged the perpetuation of enmities and feuds: afflicted parties were rewarded with “Letters of Fire and Sword,” allowing them to exact vengeance for damages done rather than seeking effective redress or resolution of underlying issues.

Nor were there effective civil institutions to administer and enforce law equitably. Agents such as Campbell of Argyll could provoke a criminal response amongst rival clans and then use his position as Justice General to punish them and reward himself with their territory. In short, the “lawlessness” of the Highlands was as much a matter of inept government policies as the inherent nature of the Gaelic society itself.

Colonization

During the sixteenth century the Scottish Crown became more organized, intrusive and demanding, seeking new ways to exert its control and to extract taxes and loyalty directly from subjects. King James VI (1566 – 1625) fashioned a monarchy even more powerful than that of his forefathers. He explicitly stated his divine right over both church and state, and devised new rituals for the Scottish Parliament and Lords which represented his position over them. To fund his grand schemes, James sought greater income from his realm and became convinced that the Highlands contained untapped sources of wealth.

King James’s book Basilikon Doron (1599) expressed his disdain of the Scottish Gaels and his desire that the isles of Scotland be planted with “colonies among them of answerable inland subjects, that within short time may reform and civilize the best inclined among them: rooting out or transporting the barbarous and stubborn sort, and planting civility in their rooms.”

In 1598 a company of ten Lowlanders – the so-called “Fife Adventurers” – were given a grant to colonize Lewis, subjugate its inhabitants and create a fishing centre in Stornoway (on the island of Lewis). Apartheid was part of the scheme: “Na marriage or uther particular freindschip to be any of the societie, without consent of the haill, with any Hyland man.” The plan was seen as useful for the subjugation of Ireland as well and the colonization of Ulster (discussed below) drove a wedge between Irish and Scottish Gaeldom.

King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England upon the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603. While the MacLeods of Lewis resisted several attempts of the Fife Adventurers to extirpate them, the threat of overwhelming force from a king who could now command the resources of three kingdoms (Scotland, Ireland and England) loomed over others. In August 1608, Lord Ochiltree (Andrew Stewart) kidnapped leading members of the Hebridean élite and held them in the Lowlands while they negotiated with the Commission for the Isles on the terms for their release.

In the early summer of 1609, Andrew Knox, Bishop of the Isles, took the results to King James in London and was commissioned for a new expedition to further the accords. Two important documents were produced in Iona in late August 1609, now often called the “Statutes of Iona.”

There is little reason to doubt that the Hebridean élite were involved in their wording and intent. King James expected that subjugation and colonization would be necessary for the reformation of the isles; Bishop Knox sought a compromise which would allow the élite to remain in place, as obedient subjects of the king and agents of the central government who would transform society from the inside. The Statutes of Iona reflect the interests of native Gaelic leaders to retain power and privilege in their territories. They focus on social and economic reform, with both chieftains and king to profit from the proceeds.

On 28 September 1609, the day on which Bishop Knox presented the documents to the Council, an embargo on the sale of cattle and horses between the Hebrides and Argyll — which the chiefs said had prevented them from being able to pay their rents — was lifted. The Statutes worked well for the next several years, with clan chiefs appearing regularly before the Council and paying rents.

Thus, by 1616, the mechanisms intended to assimilate the Gaelic élite were in place, even if they did not complete their task until after the Jacobite Rising of 1745-6. Between being educated through the medium of the English language in the Lowlands, frequent and extended sojourns outside of their home territories, and mounting debt, Gaelic chieftains increasingly compromised the social contract of clanship.

Ireland

By the beginning of the 16th century, Ireland had become fractured into power blocs dominated by highly militarized chiefs of both Anglo-Irish and Gaelic origin (often a combination of the two). This political fragmentation had been facilitated by the devolution of royal authority into the hands of semi-independent officers in Ireland as the kings of England guarded their position on the throne from rivals or carried out campaigns on the continent of Europe. Down to 1534, the most powerful rulers in Ireland were the FitzGerald Earls of Kildare and their rivals, the Butlers of Ormond.

Sitting uneasily alongside these warring factions were the colonists of the Pale, who remained loyal to English law and customs and looked to the English Crown for protection, often in vain. Although they were quick to offer their military services to the king’s lieutenant in defense of the colony against the bitter retaliation of the Irish, their relations and trust were more strongly invested in the lords who provided for their personal protection than in the distant monarch in London.

Given these differences, the colonists of the Pale did not fully surrender to the authority of the Earls of Kildare. The English Crown, however, seldom intervened in Irish affairs unless they were so volatile as to threaten England or its interests in Europe, and never committed itself in any serious and sustained way to find a permanent resolution to the divided communities and opposing cultures.

The Franciscan order of Observant Friars came in the 15th century from continental Europe to help maintain and develop the church in the Gaelic areas in Ireland. By contrast, the king directly appointed church leaders in those areas under English control. Not only did the Observant Friars act in defense of churches and their communities in Gaelic areas, they objected to the extension of the English Reformation in Ireland and mustered support for the Earl of Kildare in opposition to the Crown, portraying the struggle as a religious crusade.

This polarization spread to many of the “Old English” (as the descendants of the Anglo-Norman settlers came to be known), who took their sons out of English universities and put them into the Catholic universities of the continent, where they would not be indoctrinated by Protestant heretics. This new generation of Old English leaders were converted to the cause of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and often played a crucial role in maintaining the allegiances of the Old English community. This went as far as campaigning to withdraw their support en masse from Henry VIII.

This thus reduced the support of the king from the contingent which had previously been most consistently loyal him. Their withdrawal of religious allegiance make them ineligible for employment in government during the reign of Queen Elizabeth and her successors, who required submission in religious and secular authority. As their offices lapsed, they were replaced by Englishmen born in England who were willing to take the oaths of total submission, adding to the ill-will and resentment of the Old English élite to the Crown.

The older settled community of native Irish and Gaelicized Anglo-Irish thus formed a religious coalition which agreed upon the importance of separating political allegiance from religious allegiance, while the Crown insisted upon deference in both religious and secular authority, as demonstrated by homage to the Church of England (the Anglican Church). This worked to strengthen the allegiance of the native Gaels and Old English to the Catholic church and to see the Anglican Church as a symbol of despotism. The Gaels recognized the distinction between the Old English and the New English with the ethnonyms seanGhaill and nuaGhaill, respectively.

FitzGerald Revolts

The Earls of Kildare had long threatened to connive with Gaelic allies to make Ireland mutinous if the Crown ever unseated them. Thomas Lord Offaly, son of the ninth Earl of Kildare, made a show of defiance to Henry VIII in 1534, declaring him to be a heretic whose church reform and marital status were invalid in Ireland, and proclaiming himself to be the defender of the pope and emperor. This must have enflamed the ire of Henry VIII, who answered with an overwhelming show of force. The king sent an army of 2,300 professional troops against the FitzGeralds, successfully defeating them, forfeiting their lands, and executing all of the male members of the family (apart from an infant half-brother).

The Irish parliament was convened in 1536 and measures were hastily passed to bring the Irish church into conformity with England, under great duress. This aided in the appointment of Englishmen into high religious office in Ireland.

The removal of the FitzGeralds did remove a key stabilizing factor in Ireland and provided Gaelic lords with a pretense for insurgence and violence. The government responded with harsh reprisals and the building of military garrisons. After acknowledging their lack of success in resolving tensions, the government attempted a new strategy of accommodation: the sole surviving FitzGerald would be restored to a portion of his inheritance; English army captains would bring colonists into garrisons and supervise them; Gaelic lords willing to comply with the full authority of the king could ask for a settlement under “surrender and regrant,” but others would be dispossessed.

Under this policy, lords were required to act as executors of royal law, desist from military action, collect taxes for the royal purse, and pre-appoint a successor who would be given to an English gentleman for fosterage. These circumstances also led to the creation of a puppet government in Ireland, known as the “Kingdom of Ireland.”

Thomas Earl of Sussex, appointed as governor of Ireland in 1556, continued the policy of surrender and regrant with compliant lords. He oversaw the conquest and colonization of the “Laois-Offaly” plantation 1557-8 and periodically between 1561 and 1564 attempted to capture Séan Ó Néill of Tyrone. Ó Néill flaunted his disregard for the conditions of surrender and regrant, opting for his successor to be chosen by traditional Gaelic custom.

Newly appointed colonial officials and provincial councils, imported directly from England, were harshly critical and demeaning of Irish society, appalled by the state of Protestant reform in Ireland. In 1579, James FitzGerald of Munster, who had been in exile on the continent, returned with a small military force to Ireland. While not repudiating the right of the English Crown over Ireland, he denounced Queen Elizabeth as a Protestant heretic.

In three surviving Gaelic letters by FitzGerald, he described the goal of his campaign as “sinne ag cosnadh ár gcreideamh 7 ár ndúthaighe” (“we are defending our faith and our native land”). The rhetoric of his appeal was based on a common attachment to a church and land shared by both Gaelic and Old English communities. FitzGerald drew the enthusiasm of many in Munster and even in the Pale, but when the Earl of Desmond (in Munster) and his brother joined the rising, a major insurrection was born.

The Queen’s expedition of 8,000 soldiers defeated the rising and responded with a severity not practiced previously in executing rebels and destroying their property. The lands of the Earl of Desmond and his allies were forfeit and put into the hands of English landlords and planned for the plantation of 20,000 colonists. Although only 4,000 arrived by the mid-1590s, this event set new rigorous and harsh standards of conduct for government forces and requirements for absolute loyalty to the Crown.

As the Queen was preoccupied by wars with Spain, English officials in Ireland abused their powers to usurp property, often expecting to provoke a reaction from the local population that could be punished severely by government forces and instigate further colonization. This technique was used during the governorship of Sir William FitzWilliam 1588-94 for the piecemeal colonization of lands in Connacht and southern Ulster.

Risings and Conquest

By now, Ulster was the greatest stronghold of Gaelic culture and political resistance remaining in Ireland. Aodh Mór “Great Hugh” Ó Néill, a claimant to the title of Tyrone, had spent his youth as a client of English “adventurers” (military-backed officials aiming to colonize for their personal gain) attempting to subdue Ulster, which they had planned on subdivide and apportion in safely contained allotments to a mixture of English settlers and Gaelic members of the Ó Néill dynasty.

During his apprenticeship, Aodh Mór learnt all of the techniques of modern warfare and used them against the English to rise to power. Ó Néill took the title of “Earl of Tyrone” in 1585 and tried to expel English officials from Ulster in 1592, opposing the subdivision of territory. When Turlough Ó Néill died in 1595, Aodh Mór assumed the title “Ó Néill of Ulster.”

As his defiance of English authority mounted, he raised an army and equipped them with modern weaponry, increasing their numbers by extending the call to the peasantry (rather than restricting warfare to the professional warriors and mercenaries). He declared himself the champion of the Counter-Reformation and appealed to other disgruntled Irish lords. Aodh Mór also appealed to the Old English community by including them within his definition of the Irish people, as in his letter to James Fitzpiers in 1598:

And forasmuch as it is lawful to die in the quarrel and defence of the native soil, and that we Irishmen are exiled and made bond slaves and servitors to a strange and foreign prince, have neither joy nor felicity in anything, remaining still in captivity.

King Phillip III of Spain sent 4,000 troops to assist Ó Néill which landed in 1601 at Kinsale (in the south of Ireland). Queen Elizabeth’s massive fleet and army of 20,000 soldiers defeated the combined Irish and Spanish forces after a siege of several months that ended at the Battle of Kinsale in 1602. This was the greatest challenge ever to English supremacy in Ireland and it brought the most severe punishment ever meted out to the Irish. As Catholic landowners were seen as the greatest source of threat to English hegemony, it was argued that there should be a complete forfeiture of Catholic lands; the influence of Gaelic and Catholic ideas was to be removed by ensuring the extension of English common law to all of Ireland.

A more extensive and systematic set of forfeitures and grants of subdivided lands was made, especially in Ulster, to loyal Protestant subjects. Previous landholders managed to retain estates only by a conspicuous show of cultural conformity to English notions of “Improvement” (domesticating “wild” land and creating excess product for export in a cash economy) and civility, and by demonstrating marked loyalty to the English language and Protestant church. Indeed, it cannot be ignored that the colonial project in Ireland had long had the extermination of the Irish language and culture at its heart:

Anglicisation was neither incidental to the conduct of conquest nor a mere spin off from it. Language was intimately bound up with the ideologies that legitimised colonisation and shaped its unfolding. (Palmer, Language and Conquest)

The conspiracy by English Catholics in 1605 to assassinate King James VI/I – the Gunpowder Plot – ensured a hardening of the official policy against Catholicism, especially in Ireland. James and his administration had experience subduing the Gaelic chieftains in Scotland and believed that working with compliant native Irish chiefs, after diminishing their landholdings and power, would be the most effective policy for keeping Ulster subdued.

In 1607, however, their fortunes dwindling and their power compromised, the most powerful Gaelic lords in Ireland – Aodh Ó Néill, Ruaidhri Ó Domhnaill of Tír Chonaill and a host of about 90 other leaders – retreated on a boat for Spain in hopes of finding support to invade Ireland with the help of Catholic allies. This departure of the native élite of Ireland is remembered as The Flight of the Earls. As Spain’s fleet had been greatly reduced just before this and they did not wish to re-engage England in further warfare, these hopes were in vain.

The lands of the exiled Earls were forfeited due to their treason and made ready for colonization. Although this was to include some divisions for a limited number of loyal Irish leaders, this too was scrapped after the unsuccessful rising of Cathair Ó Dochartaigh of Inis Eóghain in 1608. More native landowners were now stripped of their lands, which were made open for settlement by loyal Protestant subjects. Some of these formed the group that were later called the “Scots-Irish” after emigrating to the United States.

Class Discussion

How does the poem “Where have the Gaels gone?” express the breaking of social norms and the violation of cultural patterns after the conquest of Ireland? What is culturally significant about the images and symbols used? What is unusual about the ethnic groups named as enemies of the Gaels in §8 and §26?

International Politics and Religion

Some of the Welsh intelligentsia attempted to elevate the prestige of Welsh and its culture through its connections with the Tudor kings. This was essentially a defensive strategy reacting against the colonizing forces of English culture, but it articulated new ideas about identity and politics with deep-reaching implications. By the mid-16th century, some scholars reclaimed the historical identity of Welsh as the original language of the entire island of Britain and rejecting the label “Welsh” as a misnomer.

Welsh religious texts of 1567 urged the Welsh people to commemorate and take pride in their role as the ancient Britons; the high literary standards of these texts reinforced the linguistic capacity and eloquence of the language itself. They argued that the Reformation should be accepted as the reclamation of the spiritual legacy of the Britons of old, rather than a resignation to the supremacy of English authority.

These radical interpretations of religion encouraged Welsh historians and antiquarians to defend their title as the ancient Britons and to depict their integration into England under the Tudor kings as the positive fulfillment of glorious Welsh destiny, rather than an experience of defeat and conquest. Anglesey, the motherland of the Tudors, was celebrated as the stronghold of the druids and the home of the kings of Gwynedd.

Welsh scholars resident in London helped to underscore the idea of a British – as opposed to strictly English – identity and polity. In books that he published between 1567 and 1580, Dr John Dee argued that Queen Elizabeth was heir to a domain in Britain bequeathed to her by her ancestor King Arthur and in North America by the Welsh mariner Prince Madoc, who supposedly sailed the Atlantic in about the 11th century. Dee was the first to articulate the idea of a British Empire which was extended its invitation of supremacy to even the Scots. His ideas helped to develop the Tudor ideology of empire and gave the Welsh a much needed ego boost during an era of English imperial expansion.

Similar ideas had been proposed by the anglophones of Scotland: cultural diffusion is facilitated by a common language and cultural developments in England were closely connected to those in Lowland Scotland of this period. Just as the similarities in language and culture formed the basis of a common affinity between the Scottish and Irish Gaels, so does it seem that Lowland Scots and the English saw themselves as sharing increasing mutual interests, one that contrasted with the Gaels. This was especially so after the Reformation in Scotland (1560).

John Mair advocated the creation of “one sole Monarchy” to “be called Britain.” Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, argued for the union of the English and Scottish crowns in 1547 because the two peoples were “so like in manner, form, language, and all conditions.” Scottish commissioners in London advocated the marriage of James Lord Hamilton and Queen Elizabeth in 1560, since Hamilton was

no straunger, but in a maner your owne countrey man, seing the Ile [i.e., Britain] is a comon countrey to us both, one that speaketh your owne language, one of the same religion. Neither yet neade youe feare any alteracion in the lawes, seing the lawes of Scotland wer taken out of England and therefor booth ther realmes are ruled by one fashion.

Such arguments, of course, entirely ignored the existence of the Celtic peoples, their distinctive languages and cultures: they were, for the purposes of those in power, non-persons. Still, in 1603, when King James VI of Scotland became heir to the crowns of Scotland, England and Ireland, the Gaelic intelligentsia were hopeful that he would prove a more merciful and benevolent ruler. They were to be greatly disappointed.

Class Discussion

What are King James’s qualifications to be king, according to “Trí coróna i gcairt Shéamais”? How does the poet describe King James ethnically? What does he imply about the historical relationships between Ireland, Scotland and England?

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

A national court for the reformed church in Scotland, called “the General Assembly,” was established in 1560. Where conversion to Protestantism in Gaelic areas occurred, it was largely due to the personal choice of clan chiefs. A few, like Campbell of Argyll, were early converts who lent the crucial support to make the operation of Protestantism in the Highlands possible.

Although James VI had been subtly promoting the Episcopalian form of Protestantism throughout his new United Kingdom, his son and successor Charles I was far more aggressive. By this time the Presbyterian form of church government – elected by congregations and accountable to them – had a firm hold in Lowland Scotland.

In 1638, the National Covenant was signed by leaders agreeing to defend the king himself but to oppose his pro-Episcopalian policies. A Covenanting (promoting the National Covenant) army marched into England and forced the king (based in London) to accept the Scottish Parliament’s abolition of Episcopalianism and the right of the Parliament to challenge the king’s authority. A series of conflicts ensued across Britain and Ireland, referred to most accurately as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Thomas Wentworth, governor of Ireland since 1633, was planning a new wave of dispossession of the Catholic landowners, who were driven by desperation to defend their positions in 1641. Probably inspired by the example of the Scottish Covenanters, the Gaels of Ulster attacked British colonists, aiming to build a “Catholic Confederacy” which could demand religious rights. The smouldering resentment of the tenantry was particularly responsible for fueling the violence, which spread throughout the country. Alasdair mac Colla Chiotaich, a Scottish Gael whose father had been driven into exile in Ireland by the Campbells, joined the insurgence.

The Scottish Covenanters entered into a Solemn League and Covenant with the English republicans in 1643 to oppose the resurgence of Catholicism in Ireland. Ulster forces joined the king’s Scottish Royalists when Alasdair mac Colla led an army from Ireland to Scotland. Under the leadership of Alasdair and James Graham, Marquis of Montrose, the Royalists won battles and terrorized Campbell lands for over a year. When their army was finally defeated, King Charles gave himself up to Scottish Covenanters. They handed him over to the English Parliament when he rejected their demand to make Presbyterianism the religion of England and was executed in 1649.

Oliver Cromwell spared no mercy in imposing his authority and the Protestant religion. He was keen to avenge what was supposed to have been a massacre of Protestants in Ireland and to cleanse the country of Catholic priests by butchering them. In Gaelic Scotland, military garrisons at Fort William and Inverness were built. The sustained conflict between Covenanters and Royalists escalated the intensity and scale of warfare in Scottish Gaeldom. It sowed bitter division between clans as they were drawn inexorably into British politics and forced to choose sides. The news of these violent clashes reinforced the stereotype of Highlanders as rebellious, bloodthirsty savages.

Wales avoided becoming a battlefield during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, although it was bled of many men and resources to pay for the wars. Wales was deeply shocked and saddened by the execution of Charles; during the reign of the Cromwellian regime, Wales was plagued by poor government, as strong men abused their power and the lack of accountability. Welsh poets lamented the upheaval of their society by aliens and men of non-noble ancestry.

The Restoration and Jacobitism

When Charles II was restored to the monarchy in 1660, the Welsh gentry were returned to their old privileges and powers, dominating a small and cowed population who were pressured to “vote” according to the wishes of landlords whenever elections were held. Economic debt and family problems allowed a shrinking number of wealthy families to monopolize a growing majority of the land and power in Wales, who grew increasingly estranged from the Welsh-speaking population.

In Scotland, the eighth Earl (and first Marquess) of Argyll, an ardent Covenanter, was beheaded for treason. The majority of Highland clans had been loyal to the king and were disappointed that the restored regime did not reward them for their loyalty but instead returned its support to the house of Argyll, who continued with their territorial expansion. In 1662, the Scottish Parliament restored bishops to the national (Episcopal) church and the authority of the Crown over them. Charles II, who had no interest in Scotland, suppressed the dissension of committed Presbyterians.

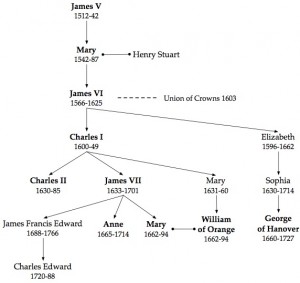

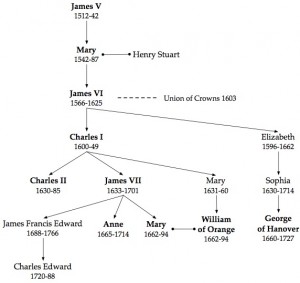

When Charles II died in 1685, his Roman Catholic brother James VII succeeded him. James fled to France in 1689 to escape growing hostility to Catholicism; those who continued to support his claim to the throne (and those of his descendants) were called “Jacobites.”

James’s son-in-law Prince William of Orange took the throne through his marriage to James’ daughter Mary. As part of the 1690 revolution settlement, the Presbyterian Church became the national Church of Scotland (albeit tied to the political interests of the London government). Ministers in Scotland were required to demonstrate their loyalty by praying publicly and explicitly for William and Mary, and in 1693 ministers were additionally required to take an oath of assurance which acknowledged the right of William and Mary to the Crown. Most bishops were unwilling to take these pledges, however, and instead maintained their loyalty to the Stewart kings, proving effective propagandists for the Jacobite cause in the eighteenth century.

Jacobitism rallied the efforts of Scottish and Irish Gaels, as well as English and Welsh Catholics, until its final collapse after the failed Jacobite Rising of 1745-6.

Beyond Britain

This era saw an acceleration of the integration of Wales not only into England but into the British Empire abroad. A larger population, greater mobility (via new modes of transport and improved roads), and economic interdependence drove the Welsh ever closer into the anglocentric sphere of activity:

The tempo of socio-economic change increased as the population began to grow and as Wales became sucked into a capitalist Atlantic economy in which the London market, overseas trade, war, and slave-trading predominated. (Jenkins, A Concise History)

The Welsh were soon engaged in imperial projects outside of Britain itself: Sir William Vaughan of Llangyndeyrn founded a colony in Newfoundland in 1617 and Welsh Quakers began to emigrate to Pennsylvania in the 1680s. Those who came were inevitably embroiled in the same range of contradictory and exploitative pursuits and activities as other European settlers.

The Act for the Better Propagation of the Gospel in Wales was passed by the Westminster Parliament in 1650, during the reign of Oliver Cromwell, to allow clergy in Wales to be removed and replaced by reformers who strove to wipe out folk traditions that were considered “unorthodox” by the strict religious prescriptions of English Puritanism.

The introduction of Puritanism in Wales led to the translation of some Puritan religious tracts from English into Welsh, such as Pilgrim’s Progress. On the other hand, some saw religious, cultural, and linguistic reform as connected and believed that Wales could not progress unless the English language and culture were imposed on the population. A series of schools were established in Wales in the 1650s to teach English. The idea that literacy and education could only happen through the use of the English language, to the exclusion of Welsh and its development, further marginalized the language in the late 17th century. The Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge was founded by the Anglican church in 1699 to run English schools in Wales.

Despite many pressures, the Welsh were tenacious about their language. Even into the eighteenth century, up to 90% of the Welsh population spoke no other language than Welsh, although English terms and phrases were beginning to penetrate Welsh life.

Treaty of Union (Scotland and England)

The Scottish parliament was suspended in 1707 and all members of the Scottish parliament were called to the Westminster Parliament in London. This act – the Treaty of Union between Scotland and England – was wildly unpopular in Scotland and believed to have been the result of bribes and intimidation.

The (Re-)Discovery of the Celts

This historical section ends at the same point in which we began our exploration of Celtic civilization from the start: with the discovery (or invention, depending on your point of view) of a group of peoples in ancient Europe called “Celts.” As has been frequently noted in this textbook, the idea of the past had important political weight and social consequences: rulers were validated by their ancestry, the pedigree of nations and dynasties added credibility to arguments about sovereignty, the legends of saintly foundations reflected the authority of religious institutions, and so on. The past has always been a way of explaining and justifying the present.

The new science of investigating the past, antiquarianism, flourished during the Renaissance. One of the most important antiquarians of the late 17th and early 18th century was Edward Lhuyd (1660-1709), a Welsh scholar who became curator at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. He carried out fieldwork in every Celtic region of the British Isles and Brittany in c.1697, meeting with the members of the learned orders, transcribing vocabulary and oral traditions in the Celtic languages, and collecting whatever ancient manuscripts he could find.

In 1707 he published the first volume of Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland; his death prevented any further material from appearing. Amongst other achievements, Lhuyd laid the foundations for Celtic linguistics, observing the split between P-Celtic and Q-Celtic languages, and arguing for the origin of P-Celtic in Gaul and Q-Celtic in the Iberian peninsula.

Besides his own research, his volume also contained texts written in Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh by learned men from these respective communities, some of which commend Lhuyd for his efforts in restoring the prestige of the Celtic languages.

Thus, while the Celtic peoples had been politically conquered and culturally suppressed by English and French empires, Lhuyd provided a new intellectual framework for scholars of Celtic cultures which has been influential in the reassertion of political power and cultural rights in the twentieth century.

Class Discussion

What does “Air Teachd On Spain” assert about the history of Gaelic in Scotland and Ireland? What does the author hope that the effect of Lhuyd’s work will be for the future of Gaelic?