Climate, Famine and Black Death

The climate began deteriorating by about the early 14th century, leading to a period of colder winters and wetter summers, poorer harvests and strains on the resources necessary to sustain the population. The “Great Famine” struck northern Europe between 1315 and 1322, followed by a similar famine on the continent 1330-1. Those whose constitutions had been weakened by these poor conditions may have been particularly vulnerable to the Black Death when it arrived in the British Isles.

The Black Death (named after the color of dead flesh) arrived on the southern shore of England in the summer of 1348 and by that winter had struck in Wales. Although the biological mechanism of the Black Death is still a matter of debate, its fatal effects on the population are infamous and pervasive, especially in urban areas: in many regions, such as Wales, about a third of the population was wiped out, resulting in major upheavals which rippled through society for some time.

Furthermore, the grim reaper was not content with a single stroke, but periodically returned throughout the 14th century, especially in 1362-63 and in 1369. The many victims of the plague came from all social classes and the widespread chaos left in its wake.

Wales

During the 14th century Welsh soldiers were heavily recruited into the military forces of English kings, who sublimated their energies into their own ambitions. Most notable of those who recruited and led them was Edward IV, the eldest son of King Edward III of England, later known as “the Black Prince.” He brought some 7,000 Welsh soldiers to the Battle of Crécy in 1346, where they defeated the French. This service to the English crown against foreign enemies was meant to help increase the loyalty of the Welsh to the English and divert their energy from rebellion.

According to a Life of King Edward II of England written in 1326, however, the Welsh still believed in the prophecies of Merlin which foretold of their liberation from English tyranny; such predictions kept alive the flames of hope and resistance. The famine of 1314-15 was accompanied by a great deal of dissatisfaction of English rule, causing Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, lord of Senghennydd, to lead an attack on Caerffili Castle in 1316. Despite deciding to surrender himself up to prevent the revolt from escalating further, he was summarily and viciously executed at Cardiff Castle.

Welsh economic conditions, already marginalized by the English conquest, were further damaged by famines and plagues, so relations were bound to degenerate as English rulers squeezed resources and manpower out of Wales in order to supply their wars in France and elsewhere. Resentment occasionally boiled over, as when leading Welshmen in the northwest killed Henry Shaldeford, the attorney of the Black Prince, in 1345.

A more energetic effort to revolt against English rule was made by Owain ap Thomas, the grand-nephew of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and last in the line of the royal house of Gwynedd. Owain, given the nickname Owain Lawgoch “Red-hand,” was born in Surrey, England, but somehow made his way to France where he led a company of Welsh soldiers to fight against the English. Although the Welsh poets anticipating his leading an army of French forces to help liberate Wales, his single attempt to do so failed when he was unable to cross the English channel in 1372. Hopes of his role as the Welsh messiah were dashed cruelly in 1378 when he was assassinated by an English spy who intercepted him in Poitou.

Owain Glyndŵr

Even this did not extinguish the Welsh dreams of freedom, however, as demonstrated by the continued activity of Welsh bards who found other messianic figures to praise. The most important of these was Owain Glyndŵr, an heroic and resourceful leader who was descended from the kings of Powys on his father’s side and from the kings of Deheubarth on his mother’s side, and was probably fostered in the house of the Anglo-Welsh judge Sir David Hanmer. He was thus born into aristocracy (probably in the 1350s) and combined learning with military experience gained while fighting in 1384 under Sir Gregory Sais in the Welsh Marches and under the Earl of Arundel while fighting for King Richard II of England in 1387.

Owain may have been provoked into action when King Henry IV, who had taken the throne away from Richard II, refused to intervene in his dispute against a Marcher lord in 1400. When he did instigate the Welsh Revolt, he was able to mobilize a wide spectrum of Welsh society in large numbers, especially in the north and southwest, because of their deep anger and resentment.

An assembly of Welsh leaders met which in 1400 declared him to be “Prince of Wales.” He had a personal seer in his retinue which enhanced his mystique and the praise of poets increased his reputation as the hoped-for deliverer of the Welsh. He and his followers were not able to battle English armies directly, so they relied on guerilla warfare and small hit-and-run raids all over Wales as their main means of harming and depleting English forces. These tactics made his band of warriors hard to capture and emboldened local resistance efforts to emulate his example. His banner, a golden dragon on a white field, drew many to its cause.

Owain and his supporters enjoyed successes over many surprisingly large and important targets in 1401: Conwy castle was captured by a small band of men; Owain led a Welsh army to victory over English troops in mid-Wales and went on to siege Caernarfon that November. In 1402, he captured two English noblemen and held them to ransom.

Some of the Welsh were goaded into action after the English parliament passed a set of Penal Laws against the Welsh in 1402 which restricted them from bearing arms, gathering for public assemblies, holding senior public office or owning property in boroughs. (Although the application of the penal laws was moderated after the Welsh Revolt was over, they stayed on the books until 1624.) By 1403, his revolt had become a national movement which had virtually reclaimed all of Wales.

Owain summoned national parliaments in 1404 at Machynlleth and Harlech, and gathered a number of Welsh intellectuals together to develop a new vision for Wales which would make it a sovereign nation with two universities (one in the north and one in the south) and a national church led by an archbishop at St. David’s. He adopted the symbols of the house of Gwynedd (his seal is above) and called on Irish and Scots leaders to lend their support against their common enemy, the English.

In that same year, he signed the “Tripartite Indenture” with Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, a formal agreement that Owain would rule Wales, Mortimer would rule the south and west of England, and Percy would take the north of England. This bid for power was strengthened when the French, at war with the English king, promised their aid.

The English Crown soon resolved to subdue the Welsh Revolt, which became increasingly vulnerable as the French and Scots withdrew from the alliance. In 1407 the English and French kings signed a treaty, freeing up the attention of King Henry to deal with Wales. Aberystwyth Castle was regained by the English in 1408 and Harlech Castle in 1409. Owain’s wife and two daughters were captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London and his attempt to attack the Shropshire border ended with disaster.

Owain disappeared after 1412; he was never betrayed by his fellow Welshmen, some of whom were tortured and murdered brutally. His whereabouts were shrouded in mystery, and although he probably died about 1416, legends about him, like other Welsh heroes, asserted that he is sleeping in a hidden cave waiting to be awoken from his slumber to lead Wales to freedom.

The loss of the last native Welsh nobleman to claim the title “Prince of Wales” and dare to challenge the English conquest was a hard one for Wales to bear. The abuse of power by the Marcher Lords continued unchecked and their rule was noted for its violence, corruption, and exploitation.

The presence of over-mighty subjects in the Marches and the general breakdown in law and order meant that Wales remained a deeply fragmented society. [...] However much a poet like Tudur Aled might preach the virtues of peace and harmony as ‘the balm of his community’, and however loudly Welsh lawgivers might champion the merits of cymrodedd (compromise) and cyflafaredd (arbitration), the sorry tale of factional feuds, warlordism, personal antagonisms and sheer lawlessness still prevailed.

As the Welsh Revolts receded, urban areas began to rebound and the Welsh themselves began to find ways of integrating into them and sharing their bounty, even in the more anglicized south. Trade networks expanded across Britain and exotic food and drink were imported from the continent to satisfy increasingly sophisticated tastes.

The Tudors

By 1483, Welsh spirits had been restored to the degree that poets once again could pen prophecies expecting the restoration of Welsh freedom. The man favoured by poets of that time was Henry Tudor, who, despite his name, was half English, one-quarter French and one-quarter Welsh.

His father’s father was Owain Tudor of Anglesey, who claimed descent from Cadwaladr the Blessed, who was supposed to have been the last native British king of Britain. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, an angelic messenger relayed a prediction to Cadwaladr that one day the Britons (of whom the Welsh were the sole survivors) would be liberated from Saxon oppression. Henry Tudor had been living in exile in France since 1471 but his uncle Jasper Tudor promoted him as heir to the throne of England via his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, a great-granddaughter of the third son of King Edward III of England.

On 1 August 1485 Henry landed in Pembrokeshire, Wales, with an army of 4,000 men, recruiting support from the Welsh by expressing concern for their downtrodden condition, which won the support of the poets who expected him to be their champion. The military forces he collected in Wales were crucial to his victory at the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August against his Yorkish rival Richard III, from whom he took the crown.

The Welsh were naturally elated that one of their own now claimed the throne of England and Wales. Although Henry – who was deemed Henry VII of England – rewarded his key Welsh allies, he had no interest in or incentive to draw attention to his Welsh ancestry or to address the grievances of the Welsh. After his gained his prize, his ears were deaf to the complaints of his supposed kinsmen.

Class Discussion

Read “Letter to the King of Scotland” by Owain Glyndŵr. What does the origin legend recount and what is its purpose?

Cornwall

In 1337 Edward III of England made Cornwall into a duchy, imposed a new local government on it, and gave it to his son to rule. Cornwall was largely left to its own devices, with little external interference, until the 17th century.

Scotland

Battles with England over Scottish sovereignty rumbled on for decades. The most celebrated hero of these efforts was Robert Bruce (r.1306-29). Although the Bruces were a feudal Anglo-Norman family, Robert’s mother was of the native Gaelic nobility of Carrick, which was then a solidly Gaelic region. His commitment to the Gaelic identity of the Scottish kingdom was manifest in his harnessing the Gaelic symbols of nationhood, such as the reliquary associated with Saint Columba, the Brecbennach, and Saint Fillan’s Bell.

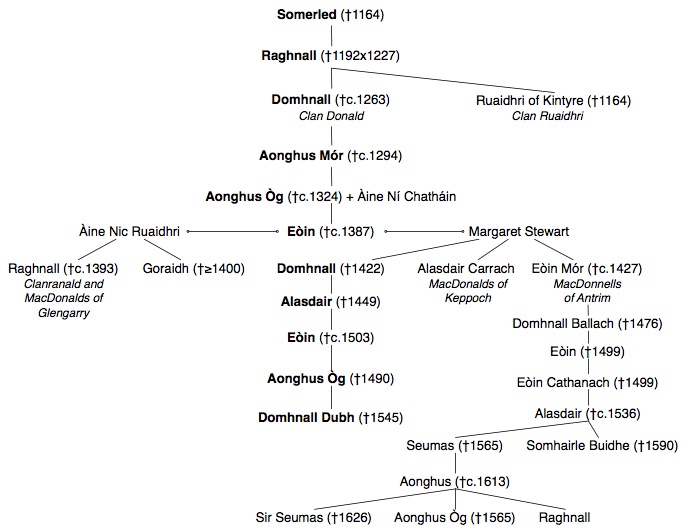

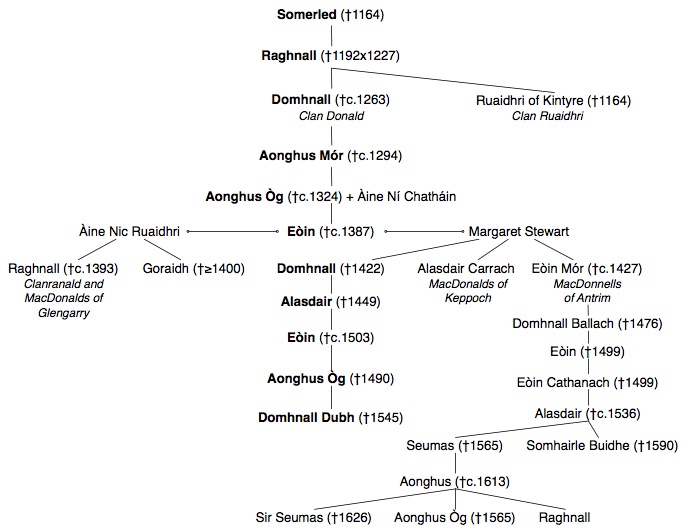

Bruce was installed as King of Scots in 1306 at the traditional site of Scone but soon was forced into exile in the Gaelic west. One of his main supporters during this crisis was Aonghus Òg of Islay, the head of the Clan Donald and the great- great-grandson of Somerled, who certainly fought with Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, when Scotland was freed from the supremacy of Edward I.

Robert Bruce required Scottish lords to relinquish lands that they held in England and he forfeited the lands held by those who had not been loyal to him. Aonghus Òg was rewarded with lands in Lochaber previously held by the Comyns; Duncan Campbell was given lands in Argyll previously held by the MacDougalls. Aonghus’s marriage to the Irish princess Áine Ní Chatháin brought a retinue of warriors and learned men who came as her “dowry” (referred to in Gaelic as tochradh nighean a’ Chathanaich), reinforcing links between Ireland and Scotland.

A document composed c.1364 during discussion about the succession of the Scottish throne demonstrates not only that the Scots were eager to maintain the sovereignty of their kingdom but that they were well aware of how effectively English kings had subjugated their neighbours and that the conceit of ethnic superiority had wide resonance in English culture:

now [that] Wales has been united to England, [...] the prelates of Wales are held in such despite in England, that they are open to the contempt and abuse of the whole people. [...]

Again that the English themselves treat the Welsh altogether, and the Irish as far as they can, so inhumanely and so like slaves that now the name and nobility of the Welsh has altogether vanished, since there is no secular lord or prelate of that race or people, and they do the same to the Irish as far as they are able, cunningly, in their way, and it is to be presumed that they would treat us more inhumanely and cruelly, whom they perceive as hitherto opposing them more seriously, and from whom they will scarcely thinking themselves safe as long as one of us survives, because of long-rooted enmity.

Class Discussion

Read the Declaration of Arbroath. What origin legend is used by the authors to explain the foundation of the Scottish nation? What does this imply about Scottish identity at this time? Why is this used to support the argument for Scottish sovereignty?

Highland and Lowland

The acculturation of personal identities went both ways in Scotland as elsewhere: Anglo-Normans assimilated in areas where Gaelic culture remained strong. Many of the large clans of the Highlands, such as the Grants, the Menzies, the Chisholms, the Murrays, the Frasers, and the Stewarts, were founded by Anglo-Normans who married into Gaelic communities and had to assimilate to local culture to be accepted by their dependents.

Other than those places that saw wholesale displacement and replacement of people, change throughout Scotland would likely have seemed gradual. The consequences, however, were such that Lowland Scotland was being assimilated into Anglophone culture and becoming estranged from its Gaelic origins. By the late fourteenth century, Scotland became polarized into two cultural and geographical zones — Highland and Lowland — whose inhabitants viewed each other with suspicion and hostility.

The irony of these stereotypes was already apparent in 1390 when the host of the “Wolf of Badenoch” attacked and burnt Elgin Cathedral: they were described as “wyld, wikkit, heland men,” despite the fact that the Wolf was the son of Robert II, Scotland’s first Stewart king, and caused as much destruction to Highland communities as Lowland.

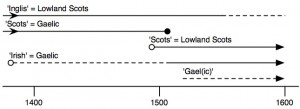

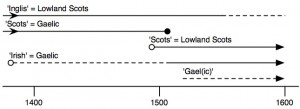

As we’ve already seen, the term “Scot” originally referred to a Gaelic speaker, whether living in Scotland or Ireland, and his language. The form of English spoken in the Lowlands was originally referred to as “Inglis,” a name which continued into the seventeenth century.

Shifts in perceptions of identity caused new terms to appear and old terms to be reassigned new usages in the speech of the Lowlands. As the Gaelic-speaking Scots were closely associated with the Irish, on account of the language they spoke as well as their culture and legendary origins, the term “Irish” (especially in the form “Erse”) began to be applied to them in the 1380s. Although “Scotice” was used for Gaelic as late as 1505, Gaelic was generally referred to as “Irish” thereafter.

From the 1520s Lowland writers such as Mair and Boece also made occasional use of terms derived from Gaelic’s name for itself. The first known use of the term “Scot” to mean the Germanic language of the Lowlands appeared in 1494 and became the dominant term in the sixteenth century.

Lords of the Isles

Eòin (aka “John”) inherited the Clan Donald leadership in 1325 and assumed the title Dominus Insularum (Latin for “Lord of the Isles”) by 1336. He was granted the island of Lewis and Harris by King David II in 1343. His first wife, Àine, was the female heir of Clan Ruairi, whose territories of Knoydart, Moidart, Uist, and Rum came into his possession through her in 1346.

In 1350 Eòin left Àine and married Margaret Stewart, daughter of Robert Stewart. In 1376 he received Knapdale and Kintyre from his father-in-law, who had become King Robert II. Eòin and Clan Donald, through marriage and political involvement, were now firmly ensconced in the upper echelons of the Scottish kingdom.

The Lordship of the Isles recreated, in effect, a Gaelic Scotland in miniature, an infrastructure for Gaelic culture after the Scottish court and Lowlands had become estranged from it. Not only did this subkingdom extend, in its prime, to nearly the entire west coast of Scotland and into the north of Ireland, but its armies could rival those commanded by the Crown itself.

The Lordship was most important in its role in maintaining a stable and peaceful order under which traditional culture could flourish. The rejuvenation of Iona, the choice of Columba as patron saint, and its inaugural rites all reflect a pan-Gaelic ethos. The Lordship provided patronage for hereditary classes of literati, lawmen, musicians, artisans and medical doctors, often importing them directly from Ireland, reinvigorating the Gaelic intelligentsia in Scotland, and establishing families of learned professionals which lasted in some cases into the eighteenth century. The success of the Lordship is physically demonstrated by the proliferation of noble residences without defensive fortifications and the restoration of monastic sites.

Domhnall inherited the Lordship from his father in about 1387. In the 1390s his younger brother Eòin Mór married Margery Bisset, heiress of the Glens of Antrim, establishing Clann Eòin Mhóir (aka “the MacDonnells of Antrim” or “Clan Donald South” in English) in the north-east of Ireland. Both Scottish and English kings attempted to exploit this link between Scottish and Irish Gaeldom in their efforts to dominate the British Isles. Kings Richard II and Henry IV acknowledged the legitimacy of Clann Eòin Mhóir’s feudal claims in Antrim, seeing them as a possible tool for restoring English rule as well as a back-door into Scotland.

Eòin inherited the Lordship from his father Alasdair in 1449 but was a poor leader. He married Elizabeth Livingston, daughter of Lord James Livingston, whose family was close to the Douglas Earls of Avondale. In 1452, King James II of Scotland murdered Earl William Douglas, sending his brother James into exile in England.

In 1462 King Edward IV of England planned to invade Scotland and made a pact with Eòin, his cousin Domhnall Ballach of Antrim, Domhnall Ballach’s son Eòin and the exiled James Douglas to divide and rule Scotland between them as subjects of the English crown. The Ardtornish-Westminster Treaty came to naught, but when King James III finally learnt of it in 1475, he demoted Eòin to a lord of Parliament and forfeited him of the territories of Ross, Knapdale and Kintyre.

Eòin’s son Aonghus Òg rallied a portion of Clan Donald around him, in defiance of his father and King James’s reduction of their status. Although Aonghus and his men managed to challenge the King’s authority and troops, he was assassinated in 1490. After a raid was made in Ross to reassert lost Clan Donald authority, James IV declared the entire Lordship forfeit in 1493. Deteriorating conditions grew worse, with the power vacuum unleashing the latent rivalries between clans, heralding the era known as Gaelic as Linn nan Creach “The Era of Plundering and Chaos.”

Class Discussion

How is the Gaelic world depicted in terms of geography and culture in Ceannas Gaoidheal do Chlainn Cholla (Headship of the Gaels for Colla’s Descendants)? How is Eòin’s right to rule legitimated?

Ireland

The territory ruled by the king of England via his vassals, the Anglo-Irish barons – the Lordship of Ireland – was at its greatest extant at the beginning of the 14th century. No Gaelic chieftain (the idea of independent Irish kings had been abolished) held land independently, but as the tenant of an Anglo-Irish earl or baron, or as the vassal of the king of England.

King Edward I of England (†1307) used Ireland primarily as a resource to exploit to fund his campaigns to conquer Wales, France, and Scotland. Internal feuds between Anglo-Irish barons were costly and disruptive and some landlords preferred to return to their estates in England rather than remain in the troubled colony. Widespread mismanagement and the redirection of resources outside Ireland led to dissatisfaction and unrest.

Robert the Bruce, king of Scotland, attempted to expand the theatre of the Scottish War of Independence against England into Ireland by appealing to the native Irish chiefs on the basis of their common Gaelic identity. He also had many family connections to the Anglo-Irish barons in Ireland.

His brother Edward had formed an alliance with Domhnall Ó Néill of Tyrone and landed with a Scottish army in 1315. He assumed the title “King of Ireland” and engaged in a disastrous three-year war in which many Gaelic leaders were killed and lands destroyed. The reduction in land productivity coincided with the general famine in northern Europe 1315-17. A generation later, the Black Death ravaged the population. In the face of insurmountable challenges, many English colonists returned home.

For the rest of the fourteenth century messages sent to England from the Anglo-Irish parliament complain insistently of decaying defences and incompetent administration in the hands of the great absentees, and prophesy the imminent ruin of the colony through reconquest by the Irish chiefs and rebellion by ‘degenerate’ or Gaelicized Englishmen. (Simms, “The Norman Invasion”

King Edward III of England (r.1327-77) concluded that the colony would only be economically profitable if it could be conquered again, subduing both the renegade Anglo-Irish rulers and the native Gaelic chiefs. He ordered absentee landlords to return to Ireland or pay for the security of their lands. Derelict lands were to be planted with new English colonists. Several major expeditions were sent from England to reinforce the colonies between the 1360s and the 1390s, but landowners were unwilling to commit their own resources to the efforts.

The “Irish problem” seemed intractable, capable of soaking up economic and military resources that needed to be diverted elsewhere. Landlords unwilling to return to Ireland or pay for defending their lands sold their estates, leading to decreased investment and interest in Irish affairs. Many of the English peasantry left the colony as well.

The decline of English hegemony in Ireland gave new hope to the Irish Gaelic chieftains of regaining lost lands and freedoms. In some areas, Gaelic rulers reasserted their control, but having all been reduced to the same status encouraged bitter rivalries that led to some of the worst violence of the era. Some large-scale consolidation of Gaelic lords and alliances between them were forged during the 15th century, as when Níall Garbh Ó Domhnaill took over Ulster in 1403 in defiance of its Anglo-Irish landlords. The native Gaelic lords, however, could not compete with the Anglo-Irish lords, especially because the latter held the more productive agricultural lands and controlled larger populations.

The authority of the king’s administration was reduced to a ring around Dublin known as “the Pale.” An earthen embankment was built around it in the late 15th century to protect its colonial inhabitants from the hostile forces around them. Even the Pale took on Gaelic practices, such as the billeting of soldiers on tenantry.

The 15th century became a period of relative stability as the Anglo-Irish adjusted themselves to Ireland, and the Irish accommodated themselves to the Anglo-Irish. There was little to differentiate the Gaelic Irish chiefs from Anglo-Irish lords: they all lived in the same stone tower-houses, employed the same mercenary troops, and were all praised by the same Gaelic literati competing for their patronage. From the late thirteenth century onwards, Irish leaders recruited heavily from the warriors of the Scottish Highlands and Islands, the gall-óglaigh (anglicized as “gallo(w)glas”).

The (Anglo-Irish) FitzGerald Earls of Kildare dominated Irish politics of the 15th century, becoming the de facto rulers of the island. They had held sway over the Irish chiefs of Meath since the 14th century and they wielded considerable influence over other areas, especially when they were able to occupy the office of Lord Deputy of Ireland (the king’s representative and the head of the Irish executive).

Having allied themselves against the rising Tudor kings of England cost the Earls of Kildare at the end of the 15th century. The king changed the nature of the Irish executive so that the terms of chief offices were no longer life appointments and their powers were curtailed and subject to the approval of the king. Kildare himself was dismissed in 1492 and imprisoned, but the agitation of his Irish allies won his freedom and return to (the newly limited powers of) his office as Lord Deputy in 1496.

Brittany

Duke Frañsez II of Brittany (1433-88) allied himself with the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I in 1487 in order to press his claims of independence from the French kings. He was defeated that year at the Battle of Saint-Aubin-de-Cormier and forced to sign the Treaty of Verger, acknowledging his subordination to the French kings and French claims to Brittany.

He died shortly thereafter and French king Charles VIII married his daughter Anne in 1491. This brought the independent line of Breton rulers to an end.