Expanding Kingdoms

Having established stable kingdoms and powerful institutions – especially the Christian church – power centres continued to expand their influence and consolidate their control over the territories and populations around them.

Christianity

Surviving evidence indicates that by the ninth century the formal institutions of paganism — the druids in particular — had been marginalized throughout the Gaelic world, with the élite eager to participate in the mainstream of European Christendom and its perceived benefits. Féilire Oengusso, a poetic calendar probably composed in the ninth century commemorating saints’ days, contrasted the decay of pagan monuments and ancient royal sites with the flourishing state of the Christian church:

The [Christian] Faith has increased,

it will endure until Doomsday,

the guilty pagans are borne away,

their settlements abandoned. [...]

The ancient fortresses of the pagans

to which title had been gained by long habitation,

are empty and without worship

like the place where Lugaid dwelt. [...]

Though it was far-flung and splendid,

paganism has been destroyed:

the kingdom of God the Father

has filled heaven, earth, and sea. (Carey, King of Mysteries)

This is, however, something of a propaganda piece which exaggerates this triumph. In fact, the ancient sites and monuments (such as the Hill of Tara) which this poem claims to have declined continued to be symbolically important in public demonstrations of political power and even retained associations with Otherworldly power, sometimes even being used in rituals of augury and magic. Nonetheless, the church did its best to insert itself into the workings of society and the exercise of power.

From the late seventh century onwards, the Columban church (centred on Iona) played a central role in the efforts of the rulers of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu to create a single, unified Pictish dynasty. The penetration of Gaels into the upper echelons of political and religious institutions accelerated the Gaelicization of the Picts. Abernethy, probably the episcopal centre of the Pictish kings, was claimed to have been dedicated to St Brigit. Atholl, the power base of the Pictish kingdom, seems to have been teeming with Irish churchmen by the early 8th century; it contains an early concentration of Gaelic church names and stone sculpture of Ionan style.

Despite the modern popularity of the idea of “Celtic Christianity,” it should be emphasized that there was no homogenous system of belief or practice, and no unified church organization, unique to the Celts and shared by them all. There were particular churches who had power and influences over others – networks emanating from certain centres, such as the Columban churches. However, there was a great deal of local variation in early Christianity, and Rome was never able to completely impose its standards and rules on all churches.

During the 8th century, Gaelic churchmen compiled and edited a collection of the canon laws and synodal decrees which had been issued during the previous centuries of the church. This collection of Latin texts, known as Collectio canonum Hiberensis, was taken by Gaelic churchmen to the churches and monasteries of the continent, where it was read and used by churchmen who were also in the process of formalizing and standardizing the regulation of European churches.

Class Discussion

What does Adomnán,Vita sancti Columbae §3.5 say about how the Columban church attempted to legitimate or delegitimate certain rulers? Why do you think they would have favoured certain men over others?

Easter Controversy

A great deal of variation existed in the evolving practices and traditions in the various branches of Christianity, but the “apolistic” philosophy of the Roman church asserted that it had the authority to impose its own standards upon disparate dioceses (an authority that was resisted in local issues of practice in many locations).

Easter – the day commemorating the resurrection of Jesus and the victory of light over darkness – was arguably the most important holiday of the Christian calendar. Although there were at least three different means of calculating the date for Easter, the Council of Nicaea agreed in 325 upon a “standard” means, which came to be called the “Roman computus.” The British and Irish churches had developed their own independent computus, however, possibly derived from the church of Gaul. Columba himself seems to have written texts that either elaborated or justified this computus.

Pope Gregory sent Saint Augustine († 604) to Britain in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons and enforce Roman standards of church practices. Augustine met with bishops and other representatives of the British church in 603 to insist that they recognize him as their spiritual overlord and that they abandon a number of their church customs and adopt Roman standards. Amongst the Augustine’s complaints was that they wore the Celtic tonsure and used a non- approved method of calculating the date for Easter. They sent him away, defying Rome’s call to change their religious customs. (Augustine went on to become the first bishop of Canterbury and is commonly referred to as the “Apostle to the English.”)

In the 630s, some southern Irish synods agreed to adopt the Roman computus, but the Columban churches (recognizing the authority of Iona) retained the older method, as did the British church. A sense of the self-confidence of Gaelic clerics in their method of calculating the date for Easter is conveyed in a letter to Pope Gregory written by Columbanus c.602 while he enjoyed the patronage of the Merovingian kingdom of Burgundy:

Given all your learning – indeed the streams of your holy wisdom radiate over the earth with great brightness, as in olden days – why do you favour a dark Easter? I am surprised, I must confess, that you have not removed this Gaulish mistake a long time ago, as if it were a wart; unless perhaps I am to think – I can hardly believe it – that you have not corrected it because it has met with approval in your eyes. [...] You must know that our teachers, the former scholars of Ireland, the mathematicians most skilled in computing the calendar, have not accepted Victorius – he has earned ridicule or tolerance rather than authority.

In 635 Saint Áedán was sent from Iona to Lindisfarne, the seat of the Northumbrian bishop, bringing other Gaelic monks with him to do missionary work amongst the Anglo-Saxons. This ushered in an era of Ionian influence in Northumbria. Amongst the practices brought with the Ionians was the “Celtic” computus. Rome must have known that its computus was still not universally accepted in 640, for on the eve of his succession to the papacy that year, John IV sent a letter to Gaelic churchmen in which he urged conformity to Roman standards.

Queen Eanfled of Northumbria had been raised in Kent, where the Roman computus was standard. She exercised great influence over her husband. According to Bede, attempting to observe two different Easter rituals (when the computi produced different dates, which did not always happen) caused tensions in the Northumbrian court. These conflicts came to a head in 664, when the Synod of Whitby was held to decide upon the question of which Easter computus to use in the Northumbrian church (as well as whether monks should continue wearing the “Celtic” tonsure or adopt the Roman one). King Oswiu (who had been educated by Gaels) was to preside over the matter, with Colmán (the 3rd Ionian bishop of Northumbria) arguing for the Celtic computus and Wilfrid for the Roman. Oswiu judged in favour of the Roman method. This marked the decline of Columban authority in Northumbria.

Although some in the British church seem to have converted to the Roman method of calculating Easter in 700, others did not until 768. Iona adopted the Roman computus in 716, and the Pictish church may have done so at the same time.

Class Discussion

Read Bede, The History of the English Church §3.25. How can we see Bede’s partiality to the English parties involved? What arguments are put forth on behalf of each computus?

Brittonic Kingdoms

During the 7th century all of the ethnic groups within Britain – Britons, Picts, Gaels, Anglo- Saxons – were fully interacting with one another in military, religious and cultural arenas. However, the overwhelming pattern was of Anglo-Saxon gains and the loss of Celtic territories. According to Bede, King Æthelfrith of Bernicia (r.593-c.616) enjoyed many victories over his British rivals: “For he conquered more territories from the Britons, either making them tributary, or driving the inhabitants clean out, and planting English in their places, than any other king or tribune.”

The ruler of Scottish Dál Riada, Áedán mac Gabráin, dismayed by this rapid expansion (and probably interested in this territory himself), led a force, including members of the northern Uí Néill of Ireland, at the Battle of Degsastan c.603 to contain Æthelfrith. Áedán’s army was defeated, however, and Dál Riatan kings were curtailed from campaigning into English territory for another couple of generations. Shortly thereafter, Æthelfrith also took control of the kingdom of Deira by expelling its king, Edwin. The union of these two (increasingly English) kingdoms, Bernicia and Deira, formed the larger unit of Northumbria (it is not certain exactly when this union was completed).

During the course of the 7th century, many of the smaller kingdoms in Wales were absorbed by larger and more aggressive ones. The kingdom of Glywysing was one such formation. The kings of Gwynedd proved important players in British politics of this era. If the conventional identification of Cadwallon “King of the Britons” with King Cadwallon of Gwynedd (r. 625-34) is correct, his career demonstrates British kings’ ability to carry out far-reaching military campaigns. In retaliation for a raid on Anglesey perpetrated by King Edwin of Northumbria in 629, Cadwallon joined King Penda of the Saxon kingdom of Mercia in battle against Edwin. Edwin was killed and defeated in 633 and Cadwallon spent a year ruling over Northumbria. He is thus remembered in Welsh tradition as a saviour figure.

Over the next century, the English kings of Bernicia and Deira effectively conquered and absorbed some northern Brittonic kingdoms. The last recorded king of Elmet was Ceretic, in the 620s. When prince Oswald returned from exile amongst the Gaels to regain the throne of Bernicia in 634, he defeated Cadwallon at Hexham. He laid siege to the Gododdin stronghold around Edinburgh 638 x 40. His brother Oswiu took over the Bernician throne after his death in 642 and continued consolidating Bernician control of the north, making use of allies amongst the Gaelic dynasty the Corcu Réti in Argyll and churchmen in Iona, as well as his nephew Talorcan, ruler of southern Pictland. Former Gododdin territories were in Bernician control by 655, allowing Oswiu to control travel between Argyll and Bernicia. He was said to have conquered further British territory in the north towards the end of his reign (670), which may have included parts of Rheged.

Despite the decline of other British kingdoms, Alt Clut enjoyed a resurgence of power in the northwest during the later 7th century: “It is difficult to ignore the evidence that the dominant military power in Atlantic Scotland in the 670s and 680s was a British one, Alt Clut being foremost among the suspects.” Gaelic forces in Lorn (Argyll) were defeated on their home turf by British warriors fighting in 677; in 681, British warriors attacked the royal fort of the Uí Choelbad dynasty of the Irish Cruithin at Ráith Mór and assassinated their king; in 681, British forces sieged the Dál Riatan stronghold of Dunadd. The king of Alt Clut probably called upon the help of his near kin, the king of Pictish Fortriu, in some of these ventures.

The Celtic kingdom of Dumnonia in the south west may have been a Roman administrative unit before reasserting its native leadership. It seems to have had an early and well developed tradition of kingship. When the West Saxon abbot Aldhelm wrote to King Gerent of Dumnonia c.693 x 7, he was clearly addressing a sovereign ruler who expected to be treated with respect. Aldhelm was trying to convince Gerent that the church in Dumnonia, over whom the king is assumed to have authority, should fall into line with the rest of the Catholic Church by abandoning their Celtic tonsure and Easter computus.

Germanic invasions took out more than half of Dumnonia’s territory in just over half a century: by West Saxon king Cenwealh at the River Parrett in 658 and West Saxon king Ine in 710 at the River Tamar. The anglicized eastern portion of Dumnonia came to be known as Devon (from Dumnonia) while the western Celtic portion came to be known in English as Cornwall. The victory of the West Saxons against a combined army of Cornishmen and Vikings at the Battle of Hingston Down in 838 marked the decline of Cornwall’s political fortunes.

It has been suggested that the power of English kings in this era relates directly to their supremacy over their Celtic neighbours, for all of the major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – Northumbria, Mercia, and Wessex – had Brittonic peoples on their “frontiers.” Being able to extract tribute from subject British peoples, or to take it from them in raids, gave ready wealth to English kings that they could use to pay for larger personal retinues, increased military forces, better weaponry, and more gifts to enhance their prestige.

Brittany

Celtic influences seemed to prevail in the early Breton church in the north and west: monastic establishments were dominant and monks wore the Celtic-style tonsure. On the other hand, Gallo- Roman church standards prevailed in Rennes, Vannes and Nantes.

Iudic-hael son of Iud-hael may have been king of Breton Dumnonia between 600 and 640. He probably led raids into Frankish territory in the east, and as a result was summoned by the Frankish king Dagobert I in 635 to pay compensation for damages, threatening military retaliation.

Iudic-hael attended the conference, although he refused to sit at the same table as Dagobert. Iudic-hael probably accepted a subordinate relationship under the Merovingian line of Frankish kings. He later retired to a monastery and was canonized as a Breton saint. As the Merovingians declined after 691, Brittany reasserted its independence.

As ever, political and social life in Brittany was complicated by the dominance of Frankish kings in the growing Frankish empire. After quelling a general revolt in 831, Emperor Louis (son of Charlemagne) called a general assembly to assign titles and duties to vassals throughout the territories he claimed. Louis made Nomenoë duke of Brittany, in return for recognizing his overlordship, and rewarded him with title to Vannes. Although leadership within Brittany was already growing increasingly centralized by the early ninth century, this external initiative solidified the idea of Brittany as single political unit, at least in theory.

Ireland

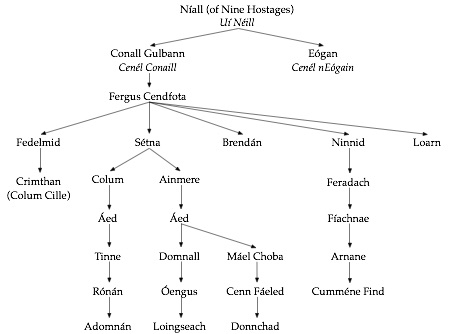

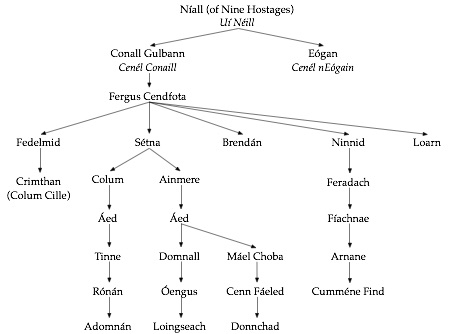

The (northern branch of the) Uí Néill emerged as the most powerful dynasty in the north of Ireland by the end of the 6th century. Still, the Ulaid (under Dál Fiatach leadership), the Cruithin (under the Dál nAraide) and Dál Riata (under branches of the Corcu Réti) continued to jostle for control.

After the death of Áedán mac Gabráin of the Corcu Réti in 609, Dál Fiatach king Fíachnae “Longshanks” (†628) consolidated his power in Ulster and reigned for 38 years, during which he was often the most powerful king in Ireland.

His son was killed in Kintyre (Scotland) while waging war against British warriors; Fíachnae may have even attacked the Bernician capital of Bamburgh on the eastern coast of Britain. After the Battle of Mag Roth in 639 in which the northern Uí Néill defeated King Congal Cáech “One-eyed” of the Dál nAraidi (Cruithin), who had been allied with Corcu Réti leader Domnall Brecc, domination of the north returned to the Dál Fiatach kings. They were defeated at the Battle of Belfast in 688 by the Dál nAraidi, however, and the Ulaid never regained their power.

Two dynasties dominated Leinster by the end of this era, the Uí Dúnlainge in the north and the Uí Cennselaig in the south, and they continued to be the major players in Leinster politics into the 11th century. Faélán mac Colmáin († 666), the king of the Uí Dúnlainge, cemented his dynasty’s power through strategic marriage with women of the houses of Fothairt and Déisi, while his brother Áed Dub († 638) must have exploited his religious connections as royal bishop of Kildare and of all Leinster.

Little reliable sources survive for the early history of Munster. The people known as the Eóganachta seem to have coalesced at an early period and displaced previous groups. Their cohesion did not endure, however, and they split into western and eastern branches. The eastern branch was based at Cashel, and at the height of their fortunes their king Cathal mac Finguine (†742) was not only king of the province of Munster but laid claim to the high-kingship of Ireland. After his death, however, the western branch gained an edge over their eastern relations, but both were under pressure from the Uí Néill.

The early history of Connacht is even more obscured by the dearth of materials. The Uí Néill were a offshoot of the Connachta and continued to exert their influence in the province. By the mid-7th century, the most powerful group was the Uí Briúin and by the end of the century they were not only the dominant power in the west but were exercising their influence in other provinces as well. They consolidated their hold in the first quarter of the 8th century and took control of the central plains of Connacht, holding court at the ancient capital of Cruachain. The only struggles over supremacy thereafter were between rival branches of the family.

In the mid-7th century the Cambrai Homily expressed the concept of three different kinds of martyrdom: the red martyrdom of actual death at the hands of pagans, the green martyrdom of physical hardship in service of God, and the white martyrdom of exile. A steady stream of educated churchmen left Ireland (and Gaelic Scotland) during the 7th and 8th centuries for the continent of Europe, founding important centres of learning and evangelism, and earning for the Gaels the reputation of scholarship and Christian zeal. The Viking attacks probably accelerated this trend of emigration of Gaelic missionaries to the continent.

Gaelic scholars were influential in the court of Charlemagne (r. 768-814), where they were joined by Italian and English scholars. Some of the manuscripts produced on the continent by Gaelic scholars feature glosses written in Old Gaelic and illustrations in the famous “Insular/ Celtic art style,” such as the St Gall codex, written at the monastery of St Gall (in modern Switzerland) c. 750.

Northern Britain

In the territory roughly corresponding to modern Scotland, there were still three major indigenous ethnic groups vying for power in political entities: Picts, concentrated in the north and north-east, other Brittonic peoples (covered previously), concentrated in the south, and Gaels, concentrated in the south-west, especially Argyll, but extending their cultural influence throughout.

Picts

As previously discussed, King Oswiu of Bernicia and Northumbria (r.643-71) became the most powerful English king of his time period, extending his power into southern Pictland in the 660s and forcing Pictish kings to recognize him as overlord. Drest son of Donuel had probably been king of Fortriu since 664; he was defeated and expelled from his kingdom while trying to expel Bernician control of Fortriu after the death of Oswiu at the Battle of Two Rivers in 671.

The new Northumbrian king Ecgfrith was probably aided in this battle by his Pictish cousin, Bridei son of Beli, who was installed as the next king of Fortriu. Bridei’s ancestors, however, seem to have been Britons, for his father had been king of Alt Clut. His reign ushered in an era of prosperity for the kingdom of Fortriu and he was the first king to be recorded as rex Fortrenn “king of Fortriu” in the chronicles. He attacked Orkney in 681 and annexed the southern Pictish zone for Fortriu 680 x 5, probably with the use of military force.

The kingdom of Fortriu seems to have had control of the kingdom of Atholl (in the central Highlands) by the 8th century to maintain its hold over southern Pictland. The name Atholl may derive from Brythonic words meaning “pass of the north,” underlining the importance of the region in travel between north and south Pictish regions.

The authority of the Columban church had been established early in Atholl, maybe even during the lifetime of Columba himself. As he consolidated his kingdom politically, Bridei son of Beli created a unified Pictish church infrastructure which claimed authority over all of Pictland. Bridei strategically decided that Iona should be the seat of the Pictish church; given that Northumbrian king Aldfrith had been a monk at Iona, the church could give Bridei leverage to discourage Aldfrith from impinging upon Pictish territory.

Not only this, but the connection with both Iona and Northumbrian must have given Bridei help in developing his ideology and practical understanding of building a kingdom. The operation of a single Pictish church helped to underscore the concept of a single Pictish ethnic group, united under a single religious leadership, as it was under the secular leadership of Bridei until his death in 692.

Fortriu was further consolidated by Bridei son of Der-Ilei, who seized the throne in 696 x 7 from Tarain (who had only held it for some 4 years). Bridei’s mother, Der-Ilei, was Pictish but his father was a Gael of the Cenél Comgaill. It may be that he hoped that his Gaelic credentials could help him push Fortriu’s powers westward, over the ridge of mountains called Drumalbane that had traditionally divided Picts from Gaels. Bridei did manage to extend Fortriu’s control over a vast range, from the east coast to the west, from the north Atlantic down to the Firth of Forth, even if he was essentially overking of a number of smaller kingdoms.

By the year 700 Pictish kings regarded Iona as being the seat of the Pictish church and indeed, as being within territory over which they claimed sovereignty in ancient times. The administrative responsibilities for the leader of Iona became too much for one man to carry with the rapid expansion of Pictland, and in 707 x 8 two administrative offices were created: one for the internal community of Iona itself, and the other for the Pictish churches.

Bridei son of Der-Ilei died in 707 and this arrangement changed dramatically under his successor, Naiton (also known in Gaelic as “Nechtan”). In 717, Naiton ejected Columban clergymen from their offices in the Pictish church and replaced them with local clergy. Despite this, the Pictish church remained influenced by the traditions which had been planted from Iona and the connections to it. The Columban legacy is marked in the form of the place names of Christian establishments all over Scotland (as shown on the above map, generated by the Saints in Scottish Place-Names project). The dissociation between the Pictish church and Iona, however, accelerated the decline of the latter in the early 8th century.

In 728, Onuist son of Vurguist defeated the southern Pictish king Elphin in battle in Moncrieff; from this base in southern Pictland Onuist captured the northern kingdom of Fortriu and reconsolidated Pictland as a whole. He 736 he attacked and captured Dunadd, and the annals refer in 741 to his “smiting of Dál Riata,” allowing him to annex Argyll into Atholl.

Bede (writing c.730) asserts that the Picts had their own distinctive language and related one place name, marking the eastern end of the Antonine Wall, which he was told was Pictish: Peanfahel. This consists of Brythonic penn “head, end” and Gaelic fahel “wall.” This indicates that Gaelic influences were already penetrating the eastern extremes of Pictland by this time. Later on, the Brythonic element penn was replaced by the Gaelic equivalent cenn, producing the modern name “Kinneil” and signifying the absorption of Pictish by Gaelic.

Class Discussion

It has been inferred that Bede relied upon a southern Pictish source composed during the reign of Bridei son of Der-Ilei for some of his knowledge of northern Britain, including claims about the origins of the Gaels and Picts. How does the text in Bede, The History of the English Church §1.1 reflect the contemporary political circumstances of Pictland and its territorial claims? Why might it be claimed that Scythia was the original homeland of the Picts?

Gaels

Although Áedán mac Gabráin left an impressive legacy in Dál Riata for his Corcu Réti kin, most of his work had come undone by the end of the reign of his grandson, Domnall Brecc (†643). After his defeat at the Battle of Glen Mureson (location uncertain) in 640, Domnall had probably had very little power outside of Kintyre. The Corcu Réti did control one of the main trade routes which brought Frankish luxury goods into northern Britain, probably exporting furs and hunting dogs in return.

King Oswald of Bernicia probably offered to aid in the protection of the Corcu Réti c.640 in exchange for the payment of tribute, allowing Northumbria to extend its influence into the Gaelic west.

To oppose this axis, the dynasty of Alt Clut formed an alliance with the Gaelic dynasty of Cenél Comgaill (in modern Cowall).

The leaders of Dál Riata seem to have cultivated Dunadd as their royal centre in the 7th century, including carving a footprint, ogam inscription, and boar in the rock at its peak, where the kings of Dál Riata were inaugurated. This site commands an majestic view of a landscape rich in prehistoric monuments, emphasizing the dynasty’s claims to an ancient and glorious past (we may debate how accurate such claims were, but now as then, the veneer of antiquity was important).

King Oswiu of Bernicia had managed to extend his control northwards over southern Pictland and north-westwards into Dál Riata. This legacy of Bernician hegemony began to be contested soon after Oswiu died in 670 and Ecgfrith came to the throne, with real struggles visible in the 680s. Ecgfrith came north to assert Northumbrian control over Pictland in 685 but suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Dún Nechtain (the location is still debated). This ended the hold that Northumbria had over the Gaelic west.

Nonetheless, the picture we have of Dál Riata in the late 7th and 8th centuries is that of a kingdom in decline. The Cenél nGabráin lost their control of the Gaelic kingdom and the Pictish kings of Fortriu dominated Argyll as overlords. Still, other Gaelic kin-groups such as the Cenél nGartnait were settling further north in Scotland and establishing new religious centres and minor kingdoms, although little textual records survive about these. These areas were soon to be overrun by Vikings, however, curtailing whatever Gaelic principalities were evolving.

Viking Invasions

As names and terms are a common source of confusion, let us begin with them. The term “Norse” is used generically of the Germanic peoples of the North; the first wave of Norse travellers were sometimes also referred to as “Norwegians.” The term “Viking” is used specifically of those whose profession it was to raid by use of war-ships. Latin texts tended to label them initially as “gentiles” (or “pagans”), in contrast to the peoples of the British Isles, who had, by now, been thoroughly Christianized; Gaelic texts also used the term Gall, which originally signified someone from Gaul but later signified a “stranger,” that is, someone from outside of the British Isles.

Gaelic hermits had retreated to northern islands as distant as Shetland, Orkney, the Faroes, and Iceland in an attempt to live an isolated life devoted to God (see Adomnán,Vita sancti Columbae §2.42). The contemporary Irish scholar Dicuil implies that hermits who had gone into exile had been dispersed by the appearance of the Vikings as early as 725:

But just as from the beginning of the world they have always been deserted, so now because of thieves, Northmen, (they are) empty of anchorites, filled with innumerable sheep and diverse kinds, many, very many, of marine birds. Never have we found these islands mentioned in the books of authors.

Indeed, recent archaeological work seems to confirm these early textual records.

Gaelic annals record the raids of the Vikings on exposed coastal monasteries and settlements (although the they may have attacked the northern islands and coast of Scotland even earlier): Lindisfarne in Northumbria in 793, the “devastation of all islands of Britain by the heathens” in 794, and the island of Rathlin (north of Ireland) in 795.

The Gaelic term Laithlind was used in early sources to designate the dwelling place of the Norse (the term eventually took the form Lochlann). Although it was later understood to refer to Scandinavia exclusively, it may be the case that it was used in the 9th and 10th century to refer to those locations in the north of Scotland (including Shetland, Orkney and the Hebrides) where the Vikings had begun to settle as early as the late 8th century.

Until about 840 the general pattern of Viking raids was of sporadic hit-and-run activity: they embarked on their boats during the warm summer months and returned home (to Scandinavia or the northern isles of Scotland) during the rough winters, making raids hard to predict and retaliation impossible. Exposed coastal communities were particularly vulnerable and monasteries, which had become veritable warehouses of wealth, were frequent targets. Iona was attacked in 802, again in 806, when 68 monks were killed, and a third time in 825 when the prior was killed. As a result, the monks fled to other, more secure monasteries located inland, both in Ireland and Scotland.

Occasionally, communities did manage to defeat the Vikings when they appeared, as when the Ulaid defeated the Vikings when they raided somewhere in Ulster in 811 and the Fir Umaill near Clew Bay (county Mayo) in 812. Still, the Vikings appear to hold grudges, for they returned to exact vengeance on the Fir Umaill in 813.

The attacks appear to become more sustained and severe from the 820s. In 821 the Vikings made off with a large number of Irish female captives. In 833 they seem to increase their range, moving from targets in Ireland solely in Leinster and Ulster to the south and east; in that year raids on Lismore (county Waterford) and south Munster are recorded.

The Vikings did not focus their attacks on the British Isles alone, but the greater number of sustained Viking attacks from about 835 may relate to the greater and more coordinated attempts on the European continent to repel the Vikings. By c.800 Charlemagne had ordered for defensive structures to be built and a naval fleet to be stationed around the coast of France to prevent further depredations. His son Louis ordered for further defensive fortifications to be built around the coast of Frisia (from modern northwest Netherlands to Denmark) in 836 and took charge of military action against them personally the next year. These actions may have been successful enough to encourage the Vikings to look for easier pickings in the British Isles.

By 835 time the Danes (a different group of Scandinavians) were trying to colonize England; they were exploring the Bristol Channel (between Wales and Cornwall), apparently looking for potential areas for settlement; they expanded their targets in Ireland and Britain to include secular communities (rather than just the more vulnerable church communities); by 837 they were targeting on the rich prizes to be gained in the Irish midlands. It is also in 837 that the first Norse name was recorded in Gaelic sources: Saxoilbh [Norse Saxólfr], the leader of one group of Vikings. This indicates that the Gaels were having more interaction and knowledge of their affairs, which greatly improved their ability to defuse the Norse threat in coming decades.