The Age of Warrior Kings

While there are few surviving documents from this era, people and events were so momentous and influential as to leave their mark on history to the present, especially through the power of literature. Among the Britons was King Arthur and Urien; amongst the Gaels of northern Britain was Áedán mac Gabráin; among the Irish was Níall Nóigíallach. These warrior-kings fought enemies and earned the praise of their poets, some of whom also left their mark on the literature of these respective cultures.

Southern Britain

The Roman army needed a steady stream of fresh soldiers to fuel its constant military expansion and was taking in large numbers of soldiers of Germanic origin during the 4th century in western regions. It was also not unusual for the Roman Empire to settle “barbarians” (people from outside the empire) onto conquered lands. Therefore, we can expect that there were Anglo-Saxons in Britain well before the Roman withdrawal.

Besides such official settlement, Germanic peoples were raiding and invading westwards into Britain and southwards into Roman territory in the third century. Roman frontiers were breached by a “barbarian conspiracy” in 367 in which Picts entered Britain from the north, Scotti from the west and Saxons from the east, and Franks and Saxons entered Gaul from the north. The Life of Saint Germanus states that when the cleric visited Britain in 429, British armies were already fighting Saxons in the island.

It has been deduced that the Britons enjoyed a major victory over the Saxons at this time and created a treaty with them which required them to aid in defending Britain against other invaders (Scots, Picts, and other Saxons). This treaty probably held until the Saxons inflicted a major military defeat on the Britons c.441, as recorded in The Gallic Chronicle. Although the Britons sent a letter to the Roman general Aetius in Gaul for help in recovering from this conquest, the Romans were busy dealing with the Germanic hordes invading the rest of Europe. It seems that the Britons had to fall back on their own native leaders.

The map above indicates the density of Anglo-Saxon burials in the 5th century, demonstrating that the Germanic peoples made their first strongholds in the best agricultural lands in Britain, in the south-east.

The Germanic peoples called those who occupied the Roman provinces walha “stranger, foreigner,” just as the Romans had called those who lived outside of it “barbarians.” This term was applied to the Britons in Britain, as well as those in Gaul. This is the origin of the name “Welsh” and “Wales” in English; it was also added to the suffix of the territorial name “Cornwall.” By the 7th century, the Britons referred to themselves with the term Cymry (from Cambrogi), meaning “people of the (same) land.”

Native Leadership

By the time that Roman forces were withdrawn from Britain (c.410 CE), many of the native subjects, especially in the south and east, appear to have switched to speaking Latin, albeit with a Brittonic accent. Despite the strong influences and assimilating pressures of the Roman Empire, Celtic languages and cultures did survive, to various degrees, in southern Britain, even in the highly Romanized east. Brittonic speech became readopted by much of the population. What appears to be 6th-century Brittonic poetry suggests that the Britons saw themselves as Christians and members of the Roman world, in contrast to the Germanic invaders; this sense of solidarity and opposition against a foreign, pagan people may even have sped the process of Christianization.

Two important northern Brittonic kingdoms in the 6th century seem to be directly descended from Iron Age ethnic groups mentioned from early Roman sources: the Uotadini (later called “Gododdin”) and the Maiatai (later called “Maithi,” who may have merged with the Domnoni).

It seems that the Uotadini were very receptive to Roman influences and collaborated with imperial officials to dominate the north during Roman occupation. There is also early evidence of Christianity in this region. The withdrawal of Roman forces seems to have diminished their power. Surviving poetry of the Gododdin, which seems to date from the late-6th/early-7th century, reads like the swan-song of a once-proud kingdom; the major body of verse, attributed to Aneirin and usually called Yr Gododdin, is about a major battle this tribe lost near the end of the 6th century at Catraeth (possibly modern Catterick, North Yorkshire), which had disastrous consequences for them.

The Maiatai, mentioned by Cassius Dio in 197 CE, were probably centred on the Manau plain just north of the eastern end of the Antonine Wall. By the beginning of the 6th century, they probably claimed the strip of territory just north of the wall, including parts of Strathearn, and had a power centre at Alt Clud (later called Dumbarton) on the west end of the Wall. (Although most of their territory was north of the wall, they seem to be better classified as Brittonic than Pictish given their interaction with the Roman Empire and their later identification as Brittonic.) By the late 6th century, the eastern portion of their territory was being threatened by the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata and by the kingdom of Bernicia.

Bernicia itself is an interesting example of early shifts in identity and power. It seems as though it was originally a Brittonic kingdom named Brynaich but Anglo-Saxon warrior-aristocrats quickly infiltrated and took over its élite layer of society. There were several other northern Brittonic kingdoms that coalesced or re-emerged after the Roman withdrawal and which are mentioned in early Celtic poetry, especially Elmet (in modern Yorkshire), Rheged (in modern Cumbria), and Strathclyde (Ystrad Clud). Of these, only Strathclyde endured the Germanic invasions past the 8th century (although the exact territory it claimed changed).

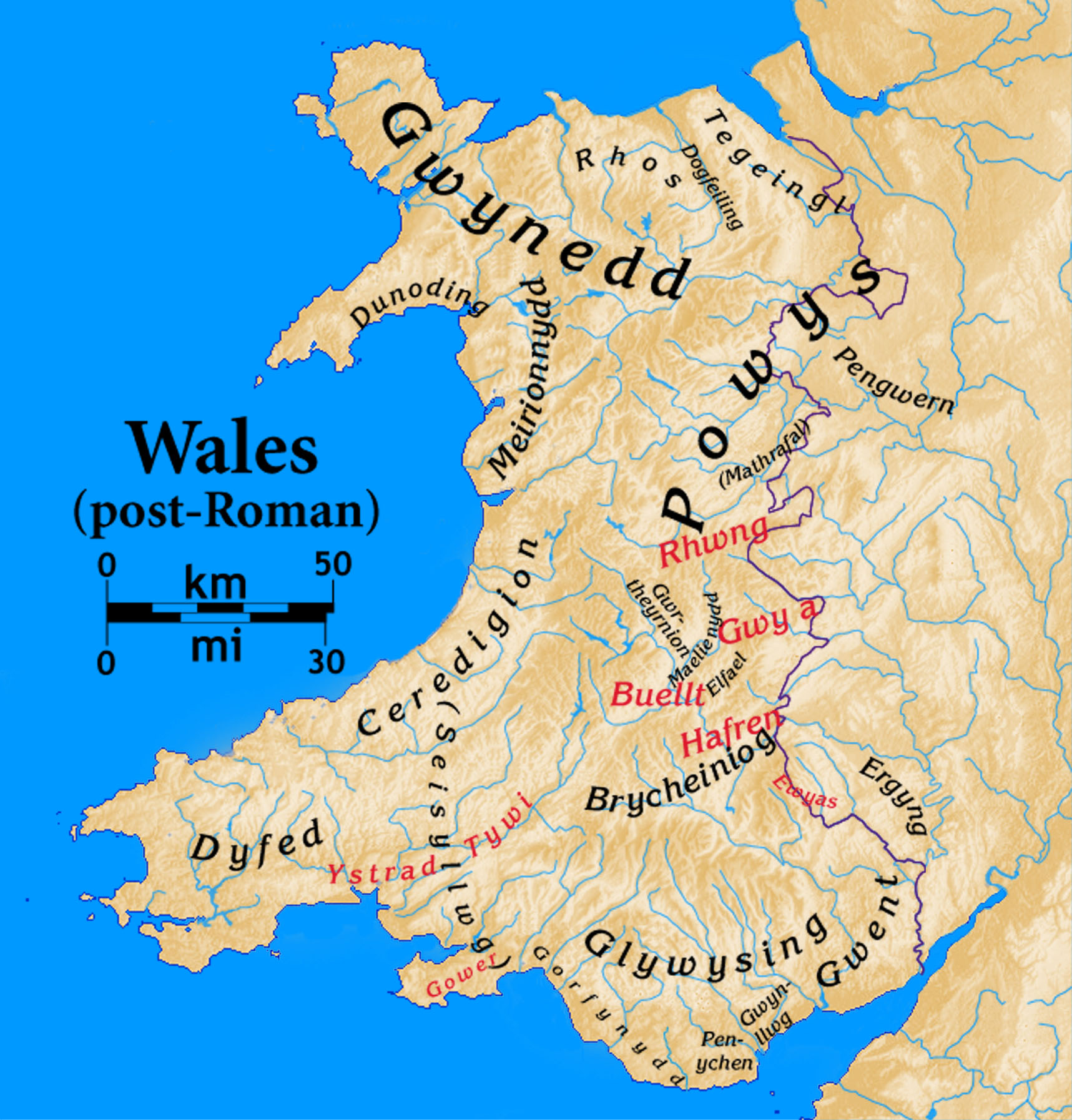

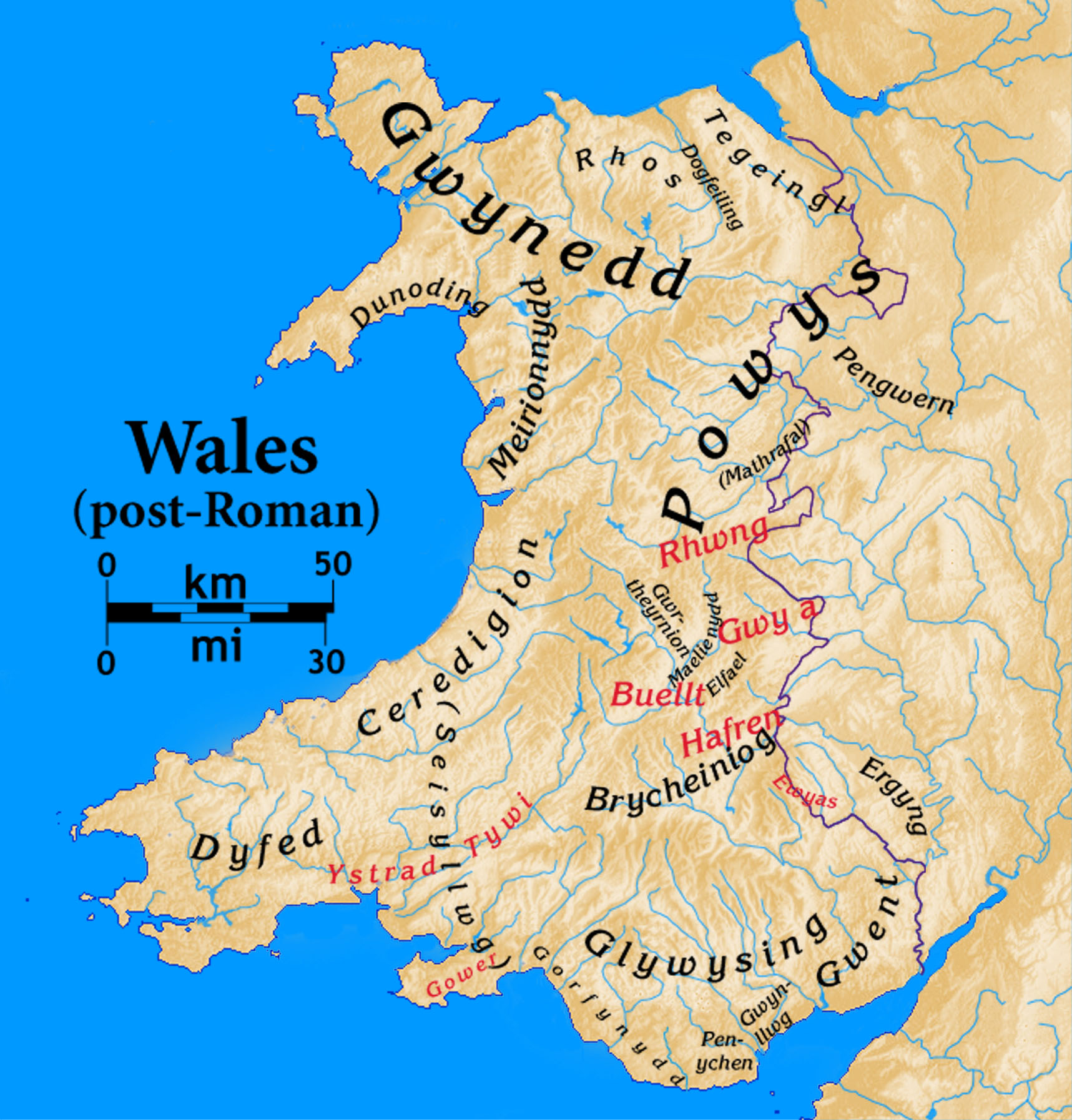

The Brittonic kingdoms in Wales, however, proved much more durable and several of them are visible in the records of the 6th century. The kingdom of Dyfed emerged from the Roman civitas of the Demetae. The rulers of Gwynedd seem to have been particularly strong; according to later tradition, the dynasty was founded by Cunedda, who, with his eight sons, led some members of the Gododdin to north-west Wales in the 5th century and expelled the Irish then inhabiting Gwynedd.

The Isle of Man seems to have been inhabited by Brittonic peoples at the beginning of this period, but the only textual record that we have is the genealogy of a dynasty from Man which survived in Wales, along with the genealogies of other Brittonic kings.

Rulers and Leadership

The Britons of the west seem to have been better equipped to organize and resist the Germanic threat than those in the east. Gildas names Ambrosius Aurelianus as the man who led British forces to a major victory against Saxons in the late 5th century.

Guorthigirn [Old Welsh “Overlord” Latinized Vortigern, Modern Welsh Gwrtheyrn], whose name is well known in later Arthurian literature, was one of the major British leaders of this early period. He was born in the fourth century, probably a native of eastern central Wales. Given that his name (or perhaps it is just a title) is Brittonic rather than Latin exemplifies a resurgence of the Brittonic languages and/or the necessity of appealing to the majority of the local population, who must have still been Brittonic-speaking. The medieval dynasty of Powys claimed him as an ancestor.

There were a number of British élite who supported the the Pelagian heresy in Britain and Saint Germanus was sent to Britain to refute them in 429. Although we do not know if Guorthigirn was among this group of supporters, Gildas condemns him in De Excidio Britanniae, where he (and others) are blamed for allowing the Saxons to come to Britain.

Guorthigirn’s son Gwerthefyr [Old Welsh “Summit-King” Latin Vortipor] led British forces in the 5th century, especially against the Jutes of Kent. Historia Brittonum §43 records three major battles in which he was involved, dying after the third, in which the Saxons were beaten back to their ships. He is remembered in Welsh tradition as one of the great protectors of Britain against the Anglo-Saxon invaders.

The British kingdoms and their rulers were not just fighting Germanic invasions, they were rivals to one another, and the self-inflicted destruction unleashed by this conflict is a common theme in early Brittonic poetry.

One of the heroic and tragic figures from this time period is Urien, probably a king of Rheged in the 6th century. According to later sources, Urien led a coalition of four British kings in a closely-matched war against Anglo-Saxon king Theodric of Bernicia. At a key point in the conflict (c.573), Theodric retreated to the island of Lindisfarne. Just before Urien could deliver the final blow to Theodric, he was assassinated by a hitman (probably Llofan Llaw Ddifro) hired by his jealous rival, Morgan (aka Morcant). A poem about Urien describes how his head was carried away by his cousin (probably the poet Llywarch Hen) as his body was consumed by ravens. This tale illustrated the damage done by the lack of unity amongst British leaders, but is doubtlessly simplified and missing crucial details.

South Wales seems to have been a region where Christianity was fostered and saints were trained who went on to travel elsewhere. Saint Dyfrig († c.550) was supposed to have converted much of the south-west of Wales, trained saints Teilo, Samson, and Illtud, and become bishop of the kingdom of Ergyng in south-east Wales (modern western Heredsfordshire). Illtud and Samson went on to Brittany, the latter founding a monastery and bishopric at Dol.

Saint David (aka Dewi, † c. 589) was a native of the south-west. He is one of the few saints to feature in early Irish religious tradition, which is not surprising given the Irish communities settled in that part of Wales in that time period. David went on to establish at church named after him and to become the abbot-bishop there. Although his cult was initially focused in the south-west, it later became a touchstone of Welsh national identity.

The bubonic plague erupted from Egypt engulfed all of continental Europe in the 540s and probably ravaged the British Isles in the 550s and 560s. This must have added to the woes of Britons in the 6th century. In the Battle of Deorham (aka Dyrham) in 577, the West Saxons defeated the western Britons near Bristol, effectively cutting off the Celtic kingdoms of Wales off from those of Dumnonia (in the southwest).

Class Discussion

How does our earliest surviving Celtic source, Gildas, De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae §23, 25, describe the Anglo-Saxon invasion? How does he depict them and the circumstances which enabled them to muscle in on British territory? What does he say happened to the native Britons as a result?

Brittany

The circumstances of the migrations from island of Britain into the Armorican peninsula – when and why they happened – are still poorly understood and the cause of great debate. There may have been a number of factors which induced the migration: plague, pressure from Anglo-Saxon or Irish invasions, and recruitment by the Roman empire to quell rebellion or defend from Germanic invasions have all been mentioned as potential reasons.

Linguistic evidence, including personal and place names, shows that a great number of Britons settled in the region, even east of the River Vilaine (which the Franks recognized as the official dividing line between themselves and Britons). Although the degree to which Gaulish survived in the region and mixed with the British language brought by immigrants is also debated, the fact that the language was closely related to Cornish and gave its name to the peninsula by 567 underscores the origin of the majority of inhabitants.

A letter written by the bishops of Tours, Rennes and Angers criticizing churchmen over the manner of their religious service to their fellow Britons attests to their presence in Armorica 509 x 521. Further evidence suggests (but cannot be confirmed conclusively) that King Conomorus (later called Cynfawr) of the British kingdom of Dumnonia also ruled in Brittany sometime in the period 511 x 558. He seems to have killed and replaced the local leader, Jonas, until the latter’s son Idwal was able to wrest power back for himself in the mid-6th century.

The Franks who came to dominate Gaul also claimed authority over the Armorican peninsula in the 6th century. Although the Bretons were not politically united, Waroch, ruler of the Veneti civitas (modern Vannes), was a central figure in Breton resistance to Frankish aggression. Waroch’s Breton forces lost a battle against the Frankish army in 578, and as a result he accepted a subordinate position under the Frankish overlordship of Chilperic. He gave his son as a hostage and agreed to pay an annual tribute in exchange for holding the city of Vannes.

Waroch, however, “set a pattern of refusal to comply with the demands of Frankish kings” and led several attacks on Rennes and Nantes in which the Bretons hauled away the grape harvests.

Even though the Franks triumphed militarily against Breton forces in battles, they could not maintain effective control over the territory and people. The area of Brittany now known as Morbihan was named Bro Weroc “Weroc’s country” after him.

Class Discussion

What does “The Legend of St Goueznou” claim about the causes for and leaders of the migration from Britain to Brittany? How does it explain the change of language and religion in Brittany?

Ireland

Irish society and culture was dramatically transformed during the period from the 5th to the 8th centuries: the Gaelic language underwent a number of phonological and morphological changes, old social structures were challenged and changed, and new leaders emerged who imposed their rule on others and ousted old rulers and kingdoms.

Many different factors may have played into these changes: famines, plagues and environmental disasters were noted in the records of this era (some of which are recorded in the Irish annals); the new Christian élite were replacing the druidic orders; and the Irish élite were being influenced by new ideas about social structures and political power via contact with the Roman and Christian world.

The older Irish order was one oriented around “tribal kingdoms” whose names tend to end in suffixes -raige “people of” or begin with elements Dál “the portion of” or Corcu “seed.” Examples include Artraige “Bear-people,” Osraige “Deer-people,” Ciarriage “Dark-people,” Dál Cormaic “the portion of Cormac,” and Corcu Modruad “Seed of My Druid.”

Some tribal names seem to have commemorated the tribal god, later turned into a founder figure and referred to in the formula common in the early tales: “I swear by the god by whom my people swear.” Tribal kingdom names sometimes survived in place names or genealogical tracts, and were occasionally taken over by the new leaders, but the actual social units were displaced by the new dynastic kingdoms just as our window into Irish history opens.

The older social order was replaced by one oriented around and for the benefit of dynastic lineages. The change in society is reflected in naming practices: whereas our earliest sources, the ogam inscriptions, mark a person’s identity by his tribal affiliation (by using the Gaelic term moccu or maqi mucoi), new designations were based on direct descent from a founder figure expressed with Gaelic terms such as Cenél “kindred,” Síl “seed; offspring,” and Uí “grandsons.”

Social transformations probably had the greatest impact on the élite of society, as the old leaders were replaced by the new, who took over their followers. In some cases, it may have led to the actual physical displacement of certain to less fertile marginal lands, which may be reflected in early traditions about the migrations of Irish tribes and the subjugation of many old tribal groups whose names end in -raige or begin with Dál by the new dynastic regime.

Of the emerging dynasties, arguably the most important of these was the Uí Néill, who claimed descent from Níall Nóigíallach “of the Nine Hostages.” This founder figure was supposed to have lived in the mid-5th century and originated amongst the Connachta (a kin-group who gave their name to the province of Connaught). The eastward expansion of the northern Uí Néill may have been one of the factors in the downfall of the Ulaid (the original inhabitants of Ulster who gave the province its name); the Dál Fiatach were the more powerful of the few branches of the Ulaid remaining by the early historical period.

Also vying for power in Ulster were the Cruithin peoples (of British origin), of whom the leading branch was the Dál nAraidi. According to early annals, the Battle of Móin Dairi Lothair was fought in 563 when an aspiring Cruithin heir asked for help from the northern Uí Néill in order to overcome his rival cousins; the Uí Néill probably gained much from the internal conflict.

The Airgialla “Eastern Hostages,” a group of (nine ?) tribes who had previously been subjects of the Ulaid, switched their allegiances to Níall and his descendants as the latter rose in power (it may be that the nine hostages who made Níall famous were given to him by the nine members of the Airgialla).

The concentration of power in the north, the tenacity of the Ulaid, and the long reach of the Irish is illustrated by the reign of king Baétán mac Cairill (r.572-81) of the Dál Fiatach, the most powerful Irish king of his time. He collected hostages from Munster and forced tribute from the rest of Ireland and the Gaelic settlement of Dál Riata in Scotland; he expelled his enemies from the Isle of Man; he forced Scottish Dál Riata to recognize his superiority.

In order to counter this power, Aédán mac Gabráin of the Corcu Réti / Dál Riata made an alliance with the Uí Néill, using Colum Cille as an intermediary at the Convention of Druim Cett in 575. This alliance seems to have survived for some fifty years.

Leinster may have been the most powerful province in this early era. The Uí Garrchon, the leading branch of the Dál Messin Corb, blocked the eastward expansion of the southern branch of the Uí Néill in the north of Leinster until the late 5th century. Their later movement southwards into Wicklow suggests that they were eventually displaced by the Uí Néill. Their neighbours, the Uí Failgi of Leinster, probably also declined after being defeated by the Uí Néill in 516.

Changes in Irish society seem to have sparked a period of great expansion and self-confidence: Irish leaders and their immigrant communities could be found in Scotland, Wales, Cornwall in the 5th century; Irish kings were dominant in parts of south-west Wales from about the 3rd to the 10th century; the Llyn peninsula was named for the Laigin (who also gave their name to Leinster); Irish kin-groups played an increasingly dominant role in Argyll and elsewhere in Scotland from the 5th century onwards.

The locations of stones inscribed with ogam in southern Britain seem to correspond closely to the areas of Irish settlement, especially those associated with the people known as the Déisi.

Migration was not only associated with military power and political expansion: so successful was the church and its associated educational system that by the end of the 6th century Irish clergy began to travel to the continent, bringing their erudition and missionary zeal with them. One of the first of these was Columbanus, who left Ireland by the year 590 and founded monasteries in Luxeuil (France) and Bobbio (Italy).

Class Discussion

Examine the evidence in The Annals of Ulster for the years 431 through 528. Why should we be cautious about the reliability of the early entries in these annals?

Northern Britain

The area of Britain north of Hadrian’s Wall, roughly corresponding to the modern country of Scotland, was home to people who might be productively divided into two or three major ethnic groups: Picts, Britons, and Gaels.

Pictland

There was probably a complex patchwork of diverse ethnic groups, all of Brittonic origin, living in the northern regions of Britain (and surrounding islands) before the Roman invasion. These were probably societies with simple social structures, and minimal class stratification or state development. The Romans preferred to negotiate with small numbers of discrete political units and authorities when they gave gifts and made treaties, and this may have facilitated the confederation of previously independent self-reliant farming communities during the Roman period.

We can be assured that Pictland was for all practical purposes a Celtic, Brittonic zone, given the evidence of personal and place names. Even the argument of a special Pictish matriarchal system which made them different from Celts has been undermined.

Roman writers as early as Tacitus refer to Pictland as “Caledonia,” apparently after one of the most important tribes there, but this name did not survive into the early medieval period as an ethnonym. That it must have been used by Celtic people themselves is evident in several place names that survive in the central Highlands, such as Dunkeld (< Dún Chaillean “the fort of Caledon”) and Schiehallion (< Sìth Chaillean “the fairy-mound of Caledon”).

There is one important “Pictish” (that is, non-Romanized Brittonic) kingdom mentioned in Roman sources that appears to be an Iron Age ethnic group who survived into the Early Historic period: the Verturiones. They were mentioned, along with the Di-Calidones, as conspirators of the Barbarian Conspiracy of 367. They seem to have been originally based around the Moray Firth and the territory just south of it. This kingdom was referred to as “Fortriu” in Gaelic sources; all of the textual documents that survive about this kingdom and its history are written either in Latin or Gaelic, even though there literate Picts, some of whom must have written in Pictish.

Burghead, the promontory fort on the Moray coast, was probably one of their most important centres of power: there are signs of occupation from the 4th century; it allowed access to marine transport; it was the centre of a bull cult for which many engraved stones have been found.

The southern Picts were probably initially Christianized by movement northwards from the northern Brittonic zone in the 5th century. A northern Pictish church can be seen operating in the Portmahomack in Easter Ross by the mid-6th century, thus predating any missionary work that might have been sent from Iona. Although the Columban monastery of Iona seems to have trained Pictish clerics who ran early monasteries in Pictland, they were probably operated independently of its authority at this time.

Gaelic Argyll

The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata emerged in the 6th century under the Corcu Réti dynasty, joining Antrim (in the north of Ireland) to Gaelic settlements in Argyll. A tradition recorded in the 10th century claimed that Fergus mac Erc and his sons were the first Gaels to settle in Scotland after leaving Ireland c. AD 500, ruling a Gaelic population which was divided into three tribal- territories: the Cenél nOengusa in Islay, the Cenél nGabráin in Kintyre, Gigha, Jura, Arran, and Cowal, and the Cenél Loairn in Lorne, Mull, Tiree, Coll and Ardnamurchan. Until recently this legend of Gaelic origins in Scotland has been taken by most historians as literal truth.

There is cause to doubt the claim that Gaelic only arrived in Scotland with these Irish colonists at this time, however; it is more likely that Gaels had been in Argyll for a considerable time longer. The chain of islands in Argyll form an archipelago between Scotland and Ireland; the modern political boundaries that we impose around Scotland and Ireland now were probably insignificant then and no serious obstacle to travel. The archaeological evidence argues for a continuity of material culture in Argyll before and after records of the kings of Dál Riata, and no evidence of typically “Irish” features suddenly appearing in the archaeological record.

The legend of this late colonization may have been promoted later in order to allow the Gaels of Scotland to share in the high cultural achievements of Ireland in the early medieval period and help to legitimate the Cenél nGabráin’s rise to power in Dál Riata. What may be more important in explaining the spread of Gaelic language and political power across the Irish sea are the Cruithin, the people who were originally Britanni but who had become Gaelic-speakers in Ireland (mostly in Ulster, but elsewhere in Ireland as well).

One of the early strongholds of the Gaelic settlements was Dunadd in Argyll, whose earliest phase of settlement is in the 4th or 5th century. Far from being a remote outpost in a backwater, excavations have shown it to be at the hub of an international trading route bringing luxury items from France and the Mediterranean. Metalworking was done there by the early 7th century. Gaelic, Pictish, and Anglo-Saxon nobility and their artisans mingled at Dunadd, making it one of the primary crucibles for the creation of the “Insular” art style.

Colum Cille, better known as “Columba” from the Latin form of his name, was a member of the Uí Néill; his noble origins allowed him to play a powerful role in the church and in secular society. Columba and a group of his followers left Ulster and settled on the island of Iona in 563, perhaps having been granted it by King Conall of the Uí Néill. Iona’s location allowed access to Gaelic, Pictish, and Brittonic kingdoms; indeed, the clerics of Iona were to play prominent religious and political roles throughout the British Isles and beyond in the next several centuries.

Áedán mac Gabráin became the leader of the Corcu Réti and king of Dál Riata in 574, holding sway over a wide sea-connected territory in northern Ireland and Argyll. His main royal fortress was probably at Dunaverty (at the tip of Kintyre). In 578 he defeated rivals who challenged his rule in a battle in Kintyre.

The death in 583 of his Irish rival Baétán mac Cairill of the Dál Fiatach, who had dominated politics in the northern Irish sphere, may have allowed him to extend his reach: Áedán waged sea-based warfare (perhaps just raiding) in Orkney; he led forces into the plain of Manau (at the eastern end of the Antonine Wall) c. 584; and probably flexed his muscles at Alt Clut in 592. His interests in the territory of the Maiatai may have come from his British wife. His wide-ranging impact is evident in the fact that he was remembered in Irish, Scottish, Welsh and Anglo-Saxon tradition. After AD 1000, all Scottish kings claimed descent from him.