Welsh Literature

The practice of professional Welsh poetry was in decline throughout the 16th century; this is not surprising, given that it became impossible for professional Welsh poets to find patrons who could give them adequate payment for their art. The native gentry, who had provide the patronage to the poets which allowed their craft to survive were becoming increasingly anglicized and spending a growing proportion of their income on luxury items which displayed their wealth and status, leaving them with less money and a lesser inclination to support the production and performance of poetry, especially after they were no longer able to understand the Welsh language.

This was a slow but inexorable decline that spanned several generations. The basic techniques and styles of the Welsh poetic tradition were inherited by amateur poets, however, allowing some continuity of the literary style to the present day.

The ideals of Renaissance Humanism spread from France to England and thence to Wales by the 1540s. Some Welsh scholars were eager to employ the benefits of new scholarship and technology on behalf of their language and culture lest they be left behind other peoples. Welsh churchmen also made the case to English authorities that translating texts into Welsh for the benefit of the majority who did not understand the English language would thwart the enemies of the king from any possible attempts to restore Catholicism to an “ignorant” populace.

Yny lhyvyr hwnn, a volume of religious texts, was the first book to be printed in Welsh in 1546. In 1547 the Welsh Protestant radical William Salesbury began publishing a more varied selection of materials reflecting the broad interests of humanist scholars, including a collection of Welsh proverbs, a Welsh-English dictionary, and texts on science and law. Salesbury aimed to develop the linguistic resources and registers of Welsh so as to accommodate a translation of the Bible into Welsh and to express the new learning of the Renaissance. Other scholars aided these efforts to enrich and expand the Welsh language by producing grammars and introducing texts modeled on Greek and Latin scholarship.

Congruent with the aims of the Protestant Reformation to make the scriptures accessible to the masses by translating them into their own vernacular languages, the English parliament passed a bill in 1563 to commission a translation of the Bible into Welsh. The New Testament was ready in 1567 but it took longer for the entire text of the Bible to be completed. Although there were several different parties involved, with differing approaches, it was the edition revised by William Morgan which made it into print in 1588. The language of this edition was written to a very high literary standard, bearing the influence of the style of the poets. This classic of Welsh literature thus helped to create a new literary standard and to form a bridge between the medieval literary tradition and later prose texts.

The New Literary Order

The Welsh humanists, despite acknowledging the bardic order as the legitimate heirs of an ancient literary tradition, were painfully aware of the poets’ adherence to conservative practices formed during a bygone age. Some wanted to enable the poetic order to renew and reform itself according to newer social and intellectual developments and rid it of the functions and stylistic conventions with clashed with the sense and sensibilities of the new age: truth and realism were to be foremost; hyperbole was to be reigned in; bards were not to seek profit for themselves by fabricating genealogies and false claims on behalf of their patrons; the latest ideas from the liberal arts and sciences were to be incorporated, as well as the rhetorical techniques of Classical literature.

The “new” free metre that emerged with the decline of the bardic order was probably the survival of an old vernacular style and genre that the old professional poets considered beneath them and unworthy of their notice. There are, therefore, very few surviving remnants of this kind of poetry from earlier periods.

Although the new free-metre poets did not use the conservative, high-register language of the old poets, their use of language is not without a degree of conscious refinement and art. Much verse is not specific to a particular dialect of Welsh but aims to be nationally accessible. Early examples of free-metre verse display a similar constraint and conventionality of expression as the older professional bardic poems, demonstrating a degree of continuity from old to new. This song-poetry was clearly still meant to be performed orally, usually sung to the tunes of popular folk songs or caroles. The popular rhymesters who performed them were known in Welsh as y glêr: the Welsh word clêr corresponds directly to an equivalent order in Gaelic Scotland known as an cliar.

Edmwnd Prys exemplifies the transition between the old literary order and the new. A highly-educated member of the clergy, he published a translation of the psalms into Welsh in 1621 and he contributed to the Welsh translation of the Bible. Rather than using the formal metres and poetic register for these verses, his version of the psalms uses vernacular forms to make them accessible to the general population.

Irish Literature

The importance of the Lebor Gabála as a body of traditional history has been noted above: all of the poets validated their patrons by reference to their descent from one of the ancestor figures in this book. It is significant in this period when the native Gaels and the Old English are emphasizing their common cause, and common claim to the land of Ireland, that some Gaelic poets were actively engaged in working the Old English into this framework of the ancient peoples who had invaded and settled in Ireland, reassessing the wisdom of maintaining the old stance of Gall against Gael.

Arguably the best and most prolific Irish poet of the 16th century, Tadhg Dall Ó hÚiginn, composed the poem “Fearann cloidhimh críoch Bhanbh” (“The land of Ireland is sword-land”) for Seán MacWilliam de Burgo (aka “Burke”) sometime between 1571 and 1580. In this poem, aimed at naturalizing the Old English amongst the peoples of Ireland, Tadhg recounts the conventional waves of invasions and adds the Old English. About the Burkes specifically, he states that they

were here to stay and determined to maintain control of their land like any other Gaelic family and accordingly deserving of respect (‘oireachta dan cóir creideamh’). The de Burgos were not to be induced to leave the island, for their right of residence was predicated on long and venerable occupation of land in Ireland (‘dul uatha ag Éirinn ní fhuil’). (Caball, Poets and Politics)

This is an important reminder that tradition is not a static, fixed entity with one meaning and purpose, but can be constantly reinterpreted and re-employed to serve the needs of the present. Even though the body of tradition embodied by Lebor Gabála was composed to serve the needs of the Gaelic community, and served to remind them of their rights in Ireland in contrast to the Vikings and other intruders, the conceptual structure of the work was flexible enough to allow new peoples and circumstances to be adapted to it.

Poets and Patrons

A number of factors conspired in the inexorable downward spiral of the old professional poetic order in Ireland during the course of the 17th century. First, the Gaelic poets, being the indigenous intelligentsia and defenders of native culture, were long seen as a threat to English colonial efforts and organizers of resistance to it, causing them to be targeted by agents of the English. Second, the poets owed their employment (and ability to acquire their training) to élite Gaelic (or Gaelicized) patrons. Hardly any powerful Gaelic lords remained after the Flight of the Earls and those who did were stripped of their estates and wealth with the implementation of the Penal Laws. Finally, as the English colonial power and common law replaced the traditional Gaelic social order, the primary social function of the poets – the legitimization of leadership – became redundant and meaningless.

The succession of James VI to the throne of England as James I provided some new hope to the Irish poetic order. Not only did James VI have proper Gaelic ancestry, but it was optimistically expected that Scottish involvement in Ireland would temper English hegemony and oppression. Between 1603 and 1607, the poets do seem to have enjoyed a boost of morale, as evidenced in the self-confidence of compositions of this period.

Several Irish élite exiled on the continent of Europe continued to be interested in Gaelic literature and historical traditions and provided some patronage for learned scholars to the mid-17th century. As colonial processes continued to unravel the social fabric in Ireland, however, centres of Gaelic learning dissolved and the last generation of formally trained poets lost their patrons, audiences and purpose. The poems composed by the old literati after the Flight of the Earls in 1607 conclude with sadness that the profession has come to an end, disdaining the crude versification of common rhymesters.

Regardless, the professional secular poets quickly fell as a social class from the top of the pecking order to the bottom. Those who wished to continue their literary efforts in some form were forced to adjust to the compromised state of Irish society by seeking out different patrons and audiences and simplifying the metres and languages that they used to make their poetry more accessible to a less educated audience. Despite this decline in status, many scholars give a positive assessment to the creative endeavours of the Gaelic literati of the 17th century who were taken out of the poet-patron relationship to address larger social issues and broader public audiences.

Class Discussion

How does “Tairnig éigse fhuinn Gaoidheal” describe the extinction of the poetic order? Why is this a national cultural catastrophe? How does the poet invoke the symbols of the past?

Counter-Reformation and Dreams of Liberation

The learned tradition did, however, find an important refuge in Counter-Reformation circles on the continent of Europe, especially at the Irish Franciscan college of Saint Anthony in Louvain, in the Spanish-occupied Netherlands. Several influential clerics worked here into the mid-17th century who had been trained in Irish poetic colleges or came from literary dynasties turned their energies towards creating high-register literature in Irish which reinforced the connection between the Catholic faith and the national Gaelic culture of Ireland.

In 1611 Giolla Brighde (aka Bonaventura) Ó hEódhusa printed An Teagasg Críosdaidhe, the first Roman Catholic manual ever published in the Irish language. Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire printed Sgáthán an Chrábhaidh in 1616 to further the work of the Counter-Reformation by directly defending Irish tradition and mocking Luther and Calvin.

The most celebrated and important Irish scholar of this period was Seathrún Céitinn (anglicized as “Geoffrey Keating”), born to an Old English family in Tipperary. He was one of 30 Irish students to leave Ireland in 1603 for the Irish College at the University of Bordeaux. After completing his doctoral degree he returned to Ireland c.1610 and received a position in Tipperary, where he completed three seminal works on Catholic theology and Irish history, most notably Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (The History of Ireland), completed c.1634.

One of the most important innovations of this era was the formulation of the aisling “vision, dream” poetic genre, usually attributed to Aogán Ó Rathaille during the Jacobite movement of the later 17th century. An aisling poem generally begins with the poet seeing a vision of a beautiful maiden who has been molested and abused by foreign scoundrels; her identity as the land of Ireland is revealed; she expresses her hope that the Stewart king – her rightful spouse – will return to Ireland, defeat and expel the alien marauders, and restore her to her former glory (and the Gaels of Ireland with her). The aisling was clearly built upon the ancient Celtic motif of the sovereignty of the land being personified as a woman who acted as spouse of the rightful king.

The themes of religious persecution and cultural conquest which pervaded the work of vernacular poets continued to influence public opinion in Irish-speaking areas.

The emphasis, time and again, in the poetry is on forced dispossession of the indigenous elites and colonisation of their land by foreigners – a fairly obvious, basic definition – and one underlined by the reiterated hope or prophecy in the poetry right down to the Famine [...] side by side with rejection of the culture of the new colonists and the colonial state went cultural assimilation and ambivalence. (Dunne, “Voices”)

Class Discussion

How does the text of Foras Feasa ar Éirinn reflect the Gaelic literati’s awareness of anglocentric propaganda? How did they attempt to counter it?

Scottish Gaelic Literature

The order of professional, learned poets (filidh) in Scottish Gaeldom were under the same pressures as their peers in Ireland for the same reasons; however, given that the Gaelic aristocracy survived in the Scottish Highlands and Isles for almost a century and a half longer than in Ireland, and a few of these had the interest and means to provide some patronage for literary activities, the learned tradition survived in Gaelic Scotland until the early 18th century. In fact, there are references to Irish poets flocking to the Highlands after the Flight of the Earls, searching for new patrons.

Scotland as a whole had been less dependent than Ireland on the formally educated poets practicing syllabic poetry (dán díreach) in Classical Gaelic who had been educated in bardic colleges. Given that this monopoly did not have such an exclusive stranglehold in Scotland, there was a wider range of poets practicing poetry for patrons of a high rank using forms of poetry not found in Ireland and simpler, more vernacular forms of Gaelic. The terms “semi-bardic” and “semi- classical” have been used to describe poetry modeled on the syllabic metres using vernacular rather than Classical Gaelic and “imperfect” rhyme. People with lesser levels of bardic training and proficiency (including aristocratic amateurs) were composing verse on subjects and for purposes other than those usually within the official remit of the filidh.

The most important Gaelic manuscript surviving from medieval Scotland is the Book of the Dean of Lismore. The variety of material in it – poetry and prose, religious and secular, in Gaelic, Scots and Latin – demonstrates the humanistic training and wide interests of the learned men who gathered and transcribed it. This manuscript includes Gaelic poems from all over Scotland and Ireland, some of them surviving in no other source. This source also provides evidence that many high-born Gaels – male and female – composed high-quality poetry according to the metrical rules of the professionally educated poets, even though they were not poets by trade.

The most prominent of the poetic dynasties in Scottish Gaeldom was the line of MacMhuirich poets established by Muireadhach Albanach Ó Dálaigh (referred to in a previous unit). One branch of his descendants became the court poets of the Lords of the Isles; after the dissolution of the Lordship, they were employed by the branch of Clan Donald known as the “Clanranald” and were given land on the Hebridean island of South Uist. Cathal (fl. 1625) and his son Niall (c.1637-1726) were highly accomplished poets of the old learned tradition. Although some earlier members of the family received training in Ireland, by this later period they were probably passing on literary skills from father to son. The last of the family capable of writing in the old style was probably Lachlann MacMhuirich, whose last literary effort has been dated to 1749.

One of the most significant surviving works created by the MacMhuirich lineage has come to be called in English the Red Book of Clanranald; it was written in Classical Gaelic on a paper manuscript by Niall MacMhuirich. This Red Book begins by recounting the origin legend of Míl of Spain coming to Ireland, so as to give the MacDonalds proper Gaelic ancestry. It then proceeds with the history of Somerled and the rise of the Clan Donald and Lordship of the Isles, and continues with the account of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

War and Religion

The increasing military role of Scottish Gaels in British political affairs reinforced the heroic ethos of Gaelic poetry, and rapid changes and tensions in the Highlands gave plenty of cause for social commentary. Royalist movements — Jacobitism in particular — mobilized Gaelic forces of traditionalism, with poets performing a lead part in the promotion of particular perspectives and campaigns, especially MacDonalds, MacKenzies, MacLeans, and MacLeods. Jacobite poets harnessed Gaelic literature of all genres and registers to a remarkable extent, attesting to the resilience and adaptability of oral tradition, and its ability to operate across the geographical span and class divides of the Highlands.

As in Ireland, religious institutions gained in importance as an employer of the educated literati as the sources of patronage amongst the native aristocracy declined. Churchmen in the Episcopal and Presbyterian church in Scotland had many opportunities to apply their literacy and literary skills in the administration of the church, giving sermons to congregations, translating church texts into Gaelic, and providing the interface between state bureaucracy and the parish. Members of the MacMhuirich poetic dynasty, as well as others, can be seen amongst churchmen throughout this period and the political role of religion offered these members of the intelligentsia opportunities to harness tradition in defense of their religious and political viewpoints.

Maighstir Seathan (anglicized as “Reverend John”) MacLean of Mull is one of the semi-learned poets of the late 17th century who found work in the church. He was a friend of the Reverend John Beaton, minister of Kilninian of Mull, one of the last professional Gaelic historians in Scotland. Maighstir Seathan obtained information about Scottish traditions and literature from Beaton on behalf of the antiquarian Robert Wodrow, librarian at Glasgow University, and composed a poem printed in the volume by Edward Lhuyd.

The output of clan bards who acted in some professional capacity, sometimes identified with the title an t-Aos-Dàna (which had previously been used as a collective term for all of the “people of the arts”), survives from the 17th century. These poets composed in vernacular Scottish Gaelic using the stressed iorram metre (often referred to as “strophic metre”). Unlike the highly personalized poems of the filidh, the clan poet addressed the larger concerns of the fine “clan élite” and relations between clans.

Even poets of inferior rank using demotic Gaelic, however, were influenced by the style and precedents of the filidh. Songs performed in the chieftain’s hall entered oral tradition to be recorded in the eighteenth century, and while Gaelic society remained stratified, oral transmission of these texts remained primarily within a small circle of relations.

In a dynasty where the Gaelic literati were fully supported, the poet and historian held distinct offices into the 17th century. Alexander Campbell drew upon the memories of older seanchaidhs when he wrote his history of the Campbells of Craignish c. 1717. He notes that the end of the MacEòghain poetic dynasty was heralded by the introduction of new media for clan history and political legitimacy:

Every considerable family in the Highlands had their Bards & Shenachies. The Bard was the Family poet, & the Shenachie their prose wryter, but very oft the Bard supply’d the place of both. These Offices were heretable, & had a pension, commonly a piece of land annexed to that Office. Their work was to hand down to posterity the valorous actions, Conquests, batles, skirmishes, marriages, relations of the predicessors, by repeating & singing the same at births, baptisms, marriages, feasts and funeralls, so that no people since the Curse of the Almighty dissipated the Jews took such care to keep their Tribes, Cadets and branches, so well & so distinctly separate. [Athairne MacEòghain], who lived in Earl Archibald Gruamach’s time, & had for his pension the Lands of Kilchoan in Netherlorne, and his son [Niall mac Athairne mhic Eòghain] were the heretable Genealogists of the Family of Argyll. This [Niall] dyed about the year 1650, and was the last of them. Printing of Hystorie becomeing then more frequent, the necessity of maintaining these Annalists began to wear off.

The professional order of the filidh was an exclusively male institution, so the looser organization of poetic practice in Scotland also allowed women to have a greater voice in literature than in Ireland. In fact, many of the most influential poets in this period were women and some of their poems had just as much as much political argumentation as their male counterparts. On the other hand, there is also evidence that there were attempts to silence or suppress some female poets because they exerted themselves too assertively.

Class Discussion

How does “Air Teachd On Spain” reflect the actual history of Gaelic learning and its influence in Europe? What origin legend(s) does he draw upon?

Gaelic Music

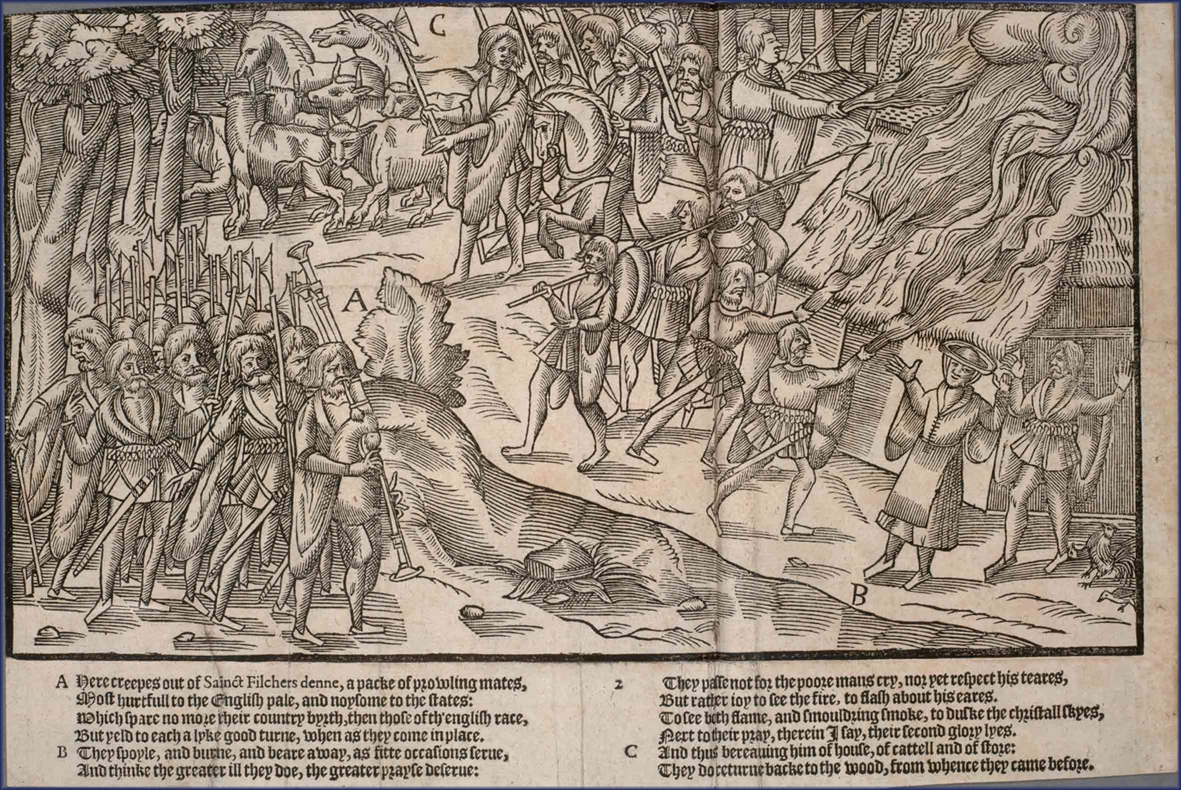

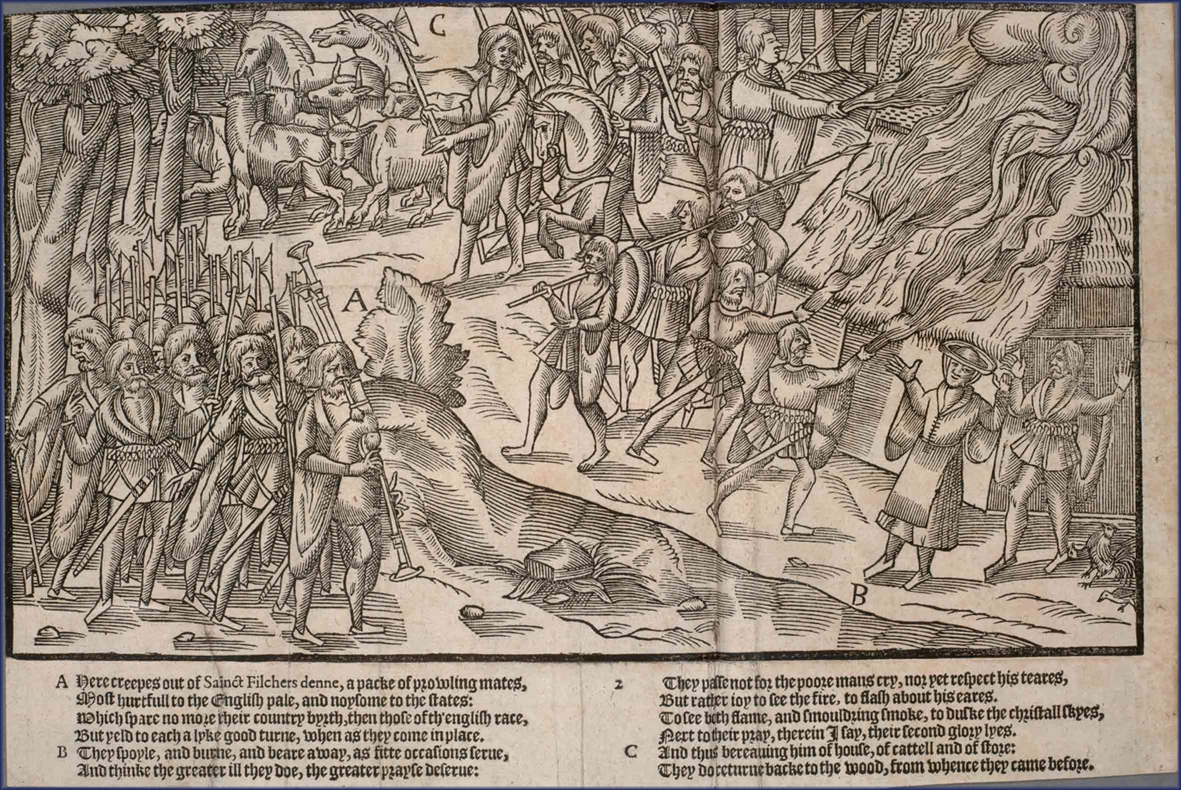

By the beginning of this period the bagpipe was in use in Gaelic Scotland and Ireland, developing more of a musical tradition and mutating into many different forms as time went on. The earliest illustrations of what we would now call the “Great Highland Bagpipe” were made not in Scotland but in Ireland, such as the well-known woodcut by John Derricke c.1578 depicting a troop of warriors led by a bagpiper (see below).

A portrait of four Irish people at the English court in the mid-sixteenth century by Lucas de Heere also includes the bagpipes.

The early bagpipe, however, was not represented, and apparently not perceived, by the Highland élite as a musical instrument per se, as was the clàrsach, but rather as an implement of warfare used to lead soldiers, intimidate enemies, and send battle signals. These were precisely the functions of the contemporary trumpet, used throughout medieval Europe to make announcements and invoke particular moods for events. Like the trumpet, the bagpipe carried the banner of the aristocrat with whom the player was associated.

Unlike the clàrsach, the bagpipe does not appear in any Classical Gaelic verse. The early bagpipe faced a well-entrenched monopoly of the clàrsach and the file in Gaelic society, many of whom saw it an unwelcome upstart. Advocates of the bagpipe helped to make it accepted as a musical instrument worthy of the patronage of the élite by adapting some of the institutional trappings of the schools of the filidh and clàrsairean, utilizing some of the same teaching methods, playing and composing in established genres, and using Gaelic poetry itself to assert a niche for the bagpipe. The prestige of the bagpipe in general was no doubt enhanced by its functions in battle during a time when the intensity of warfare was escalating.

Like the file, professional bagpipers became the full-time employees of chieftains, granted lands rent-free near their estates and were responsible for performing at the chieftain’s request, as the tract A Collection of Highland Rites and Customs (c.1685) recorded: “Pipers are held in great Request so that they are train’d up at the Expence of Grandees and have a portion of Land assignd and are design’d such a man’s piper.” Like the filidh and clàrsairean, professional bagpipers prided themselves on their social rank and expected to be treated accordingly. There are also indications that a number of the tunes that became adopted into the bagpipe tradition had originally been played on the clàrsach.