Literacy In Continental Europe

The concept and practice of literacy is believed to have been first invented (for the peoples of Eurasia) in ancient Egypt. The idea was borrowed and developed by various other peoples who created their own writing systems to represent their own languages when they had a function for it, usually to support the record-keeping needs of growing bureaucracies. The Phoenician (aka Proto-Canaanite) alphabet, in use by about 1050 BCE and representing only consonants, seems to be the ancestor of Greek, Aramaic, and ancient Hebrew scripts, and thus is the ancestor of all writing systems now used in Europe. Thus, even the Greeks, Romans, and Jews acquired literacy from other peoples. The first Celtic community to adopt literacy – the Lepontii of Cisalpine Gaul (see next section) – did so at about the same time as the Romans themselves: the early sixth century BCE.

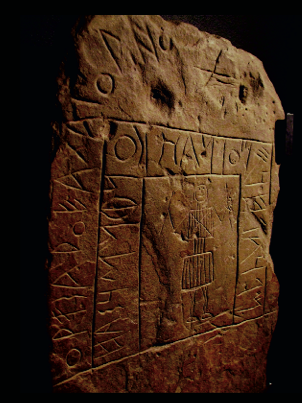

Celtic inscriptions occur on stones (shrines, burial stones, territorial markers), on coins, on curse tablets, and on calendars. Some of these inscriptions, which have only recently begun to be understood, provide exciting insights into Celtic life and history.

The adoption and development of literacy did not happen at one time and place for all Celts, but in highly localized circumstances, depending on the socio-economic developments within and specific to that Celtic community as well as the external influences and borrowings. In an age when we take literacy for granted, it is worth stressing that people – particularly the élite – had to be motivated to learn how to read and write by some function or perceived need that literacy provided. This might include social leaders seeking to enhance their prestige by creating monuments inscribed with their names, craftsmen and artists identifying their creations by inscribing their names, householders marking their possessions with their names, political leaders creating legally binding records of contracts or transactions, or religious leaders impressing their followers and the gods with their ability to create a permanent memorial of words associated with religious ceremony or spiritual power.

Early Literacy in Iberia

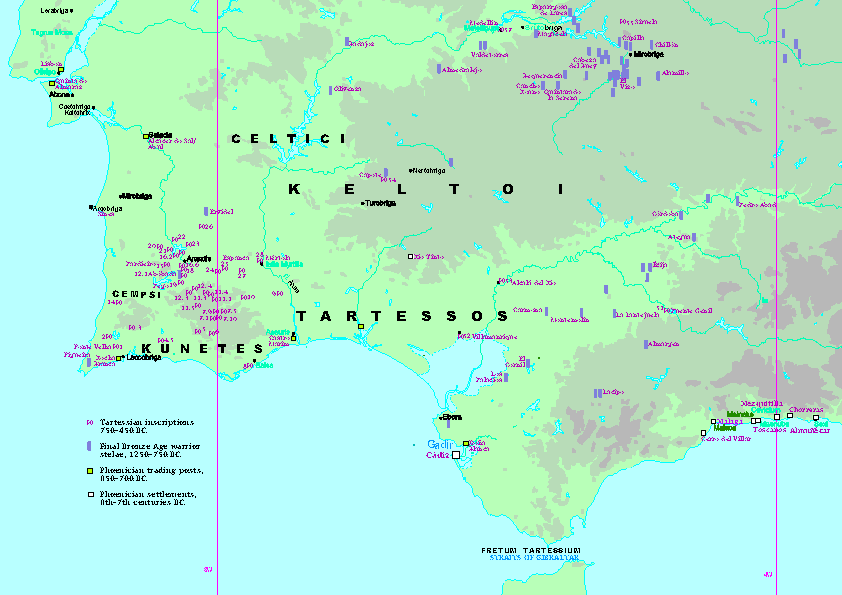

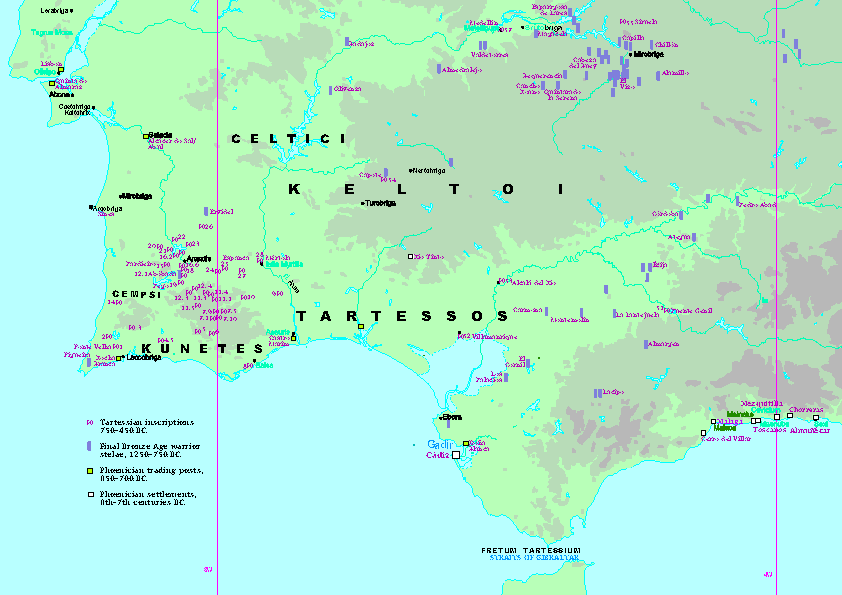

Writing was introduced into the far west of Europe when the Phoenician colony of Gadir (modern Cádiz) was established in south-western Iberia early in the first millennium BCE. The native peoples of Iberia eventually adapted the Phoenician script for their own languages, no later than the late fifth century BCE.

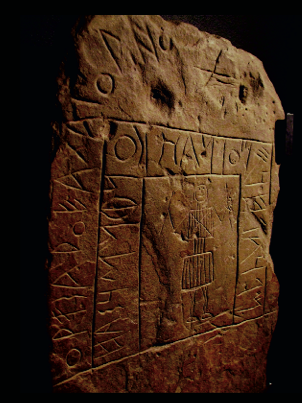

There is also a language called “Tartessian” in inscriptions near the Phoenician colony written in Phoenician script dating back to the eighth century BCE.Several scholars have noted features of Tartessian which are also characteristics of early Celtic, or have identified Celtic names or elements in these inscriptions. John Koch has recently claimed Tartessian to be Celtic in entirety, although this theory is still hotly debated.

Lepontic

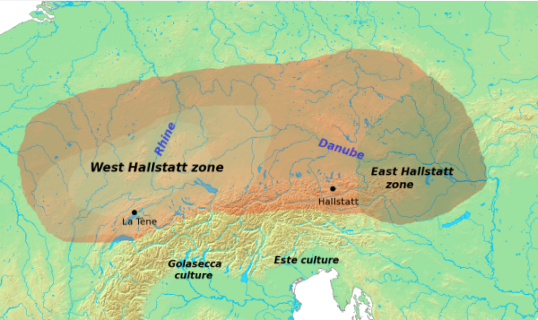

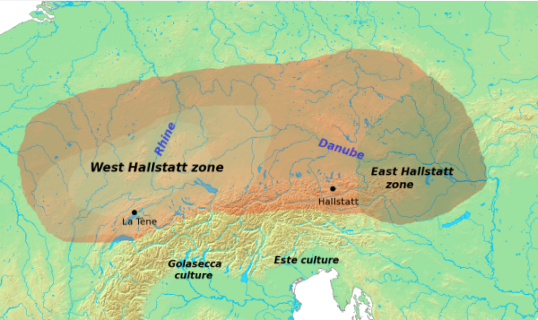

In the eighth century BCE the Etruscan culture of northern Italy adopted the writing system of the Euboean Greeks. As Etruscan civilization flourished under its aristocratic leaders, exercising its military and economic might, it in turn influenced other communities within its orbit. Not only did the Romans borrow the Etruscan alphabet for their own use, but so did the Celtic community now called the “Lepontii” (the “Golasecca culture” in archaeological terms) living near and in the foothills of the Alps and the lakes of Lombardy.

Many of the 140 Lepontic inscriptions currently identified were engraved on funeral stones or other monuments likely meant to enhance the social prestige of local élite or confirm their possession of territory; a few record personal names on ceramics and sixteen are on coins.

One of the oldest inscriptions, dated 580x550 BCE, is the personal name of a Celtic male carved into a funeral monument at Castelletto Ticino.

The Vergiate inscription was written on a funeral stone c.490 BCE in the far north of Italy, closely resembling Etruscan styles. Dr Joseph Eska has called this “the oldest Celtic poem,” suggesting that we can interpret this inscription as: “For B., D. enclosed/set up the burial precinct; he erected the Pala-stone.”

One of the most curious, and earliest, Lepontic inscription is an engraved boar’s tusk far west from where we would expect to find it: in Gaul. An interpretation of the brief inscription suggests that it was dedicated to the gods Esus and Taranis.

Iberian Script in S-W Gaul

Iberian merchants introduced their language and writing system into the south-western region of Gaul later associated with the province of Languedoc by the fourth century BCE, and a few Celtic personal names, indicating ownership of items, already appear in the area in the fourth century BCE. Although the evidence indicates that wealthy Celts were doing business with these Iberian merchants and even able to write in Iberian, it does not appear that the Celts of this region adapted Iberian script for writing their own language.

Greek Script in Gaul

The Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marsaille) was established on the southern coast of Gaul c.600 BCE, thus introducing the Greek language and script into Gaulish territory. Despite the long period of contact with Greek civilization the first evidence of Gauls writing in Greek using the Greek script only appears in the third century BCE and of Gauls adapting the Greek script for writing in Gaulish in the second century BCE. The use of this “Gallo-Greek” script quickly spread thereafter through many parts of Gaul in many variations and was used for a wide variety of purposes, including legal transactions, ownership graffiti, artist identification, and funeral memorials. The earliest example of this adoption may be the Montagnac Column.

The inscription on the Vaison-la-Romaine Stone dates from before the Roman invasion and commemorates a Celtic leader dedicating a sacred site to the goddess Belesama.

It certainly appears that growing Celtic communities were taking on the apparatus of urban civilization, including literacy. Julius Caesar stated a census was taken by Celtic tribes before they embarked on a large-scale migration and that his scouts found these documents (§1.29):

In the camp of the Helvetii, lists were found, drawn up in Greek characters, and were brought to Caesar, in which an estimate had been drawn up, name by name, of the number which had gone forth from their country of those who were able to bear arms; and likewise the boys, the old men, and the women, separately.

It is interesting that a similar sort of census, relating to military capacity, was drawn up by the Scottish Dál Riata in about the 7th century.

Celtiberian

The Celtiberians began issuing coins that bore Celtic names as early as the third century BCE. They did not begin to adopt the Iberian script widely until the second century BCE, however, about the same time as the Romans began to conquer the region. There are several types of inscriptions in Celtiberian, including religious dedications, ownership graffiti, and contracts commonly called “hospitality tesserae” between cities and individuals or groups. The longest of these inscriptions – on the Botorrita I tablet – is about 200 words long.

Another vital resource for Celtiberian literacy, and the language itself, is the Botorrita III tablet, discovered in 1992. It contains a list of nearly 250 names in four columns, both men and women.

There is a set of inscriptions, some in Iberian and some in Hispano-Celtic, on the limestone wall of a very high mountain site at Peñalba de Villastar (Aragon of modern Spain), which was probably a sacred ritual site dedicated to the god Lug. These inscriptions are generally believed to date from the second century CE and written in Roman letters. One recent translation takes it to mean: “To the mountain dweller as well as ... to the Lugus of the Araians, we have come together through the fields. For the mountain-dweller and horse-god, for Lugus, the head of the community has put up a covering, (also) for the thiasus a covering.”

An interesting outlier in the Celtiberian corpus is the inscription on the island of Ibiza. It is the only example found thus far of a Celtiberian memorial stone.

Celtic Coinage and Literacy

Celts probably first came in contact with coinage when they were paid as mercenaries in the Mediterranean. In the 3rd century BCE Celtic nations as far west as Armorica began to mint their own coins, first in imitation of foreign (especially Greek and Roman) coins but later of their own design.

Caravos, leader of Celtic Tyle (in modern eastern Bulgaria), issued silver tetradrachms and bronze coins as early as the 3rd century BCE which carried his name.

Widespread adoption of Celtic names on coinage, however, did not become widespread until the 1st century BCE, when it appears both east and west. Inscribed coins in Gaul were issued in pre-conquest Gaul at Villeneuve-Saint-Germain, for example, and Dumnorix issued coins with his name while attempting to unite Gaul against the Romans. The Boii of Pannonia and the eastern-central Gauls also began to use Latin script in this era to write the names of the rulers or kingdoms on their coins.

Galatian coin inscriptions were short-lived and represent the brief assertion of autonomy before Roman conquest. The only known silver Galatian coins are those issued during the reigns of Brogitarix and his son Amyntas.

Celtic Literacy in Britain

Evidence for literacy in Celtic languages in Britain includes inscriptions on coins. As we might expect, contact with and domination of the Roman Empire (and the empire as a channel for the spread of Christianity) was a real watershed in the history of literacy on the island.

Pre-Roman Literacy

A few of the most powerful kings of southern Britain were beginning to issue their own coins in the decades before the Roman invasion of 43 CE, as evidenced by a hoard of coins found in the year 2000 in southeast Leicestershire (called “The Hallaton Treasure”).

A gold quarter stater dating from the decades before the Roman invasion contains the words “Camu” on one side, signifying the mint at Camulodunum, modern Colchester in Essex, and “Cuno” on the other, signifying king Cunobelin, who reigned from c.9 CE to c.40 CE. This coin was minted during his reign. While the horse associated with the king signifies his royalty, the stalk of grain associated with the place probably signifies the agriculture wealth underlying the region’s economy in general.

The coins minted by the Iceni show Roman influence even before Claudian invasion of 43 CE – probably due to links established during Julius Caesar’s initial expedition into Britain – but the coins of the Corieltauvi (to the north-west of the Iceni) appear to be earlier than those of the Iceni and do not show direct Roman influence. The Catuvellauni were also issuing coins with inscriptions on them before the Roman invasion of Britain, the first of which seem to have been minted by king Tasciovanus. In 2012, a set of 10 gold coins were found in Leicestershire which were originally minted in northern Gaul 60 x 50 BCE, indicating that there were active links between Celtic Britain and Gaul before the Roman conquest. Such connections may have been responsible for introducing social and economic innovations such as the use of coinage into Britain.

Coinage issued by Celtic rulers in Britain has been surprisingly important in recovering names not otherwise recorded by historical documents. Coins found between 1997 and 2010 contained four names – Sam, Solidus, Touto, and Anarevito – that were previously unknown.

Roman-Era Literacy in Celtic Languages

There may well have been a limited degree of literacy in the Old Brythonic language amongst some of the Romano-British élite during Roman rule: this is suggested by a large number of Celtic names appearing in inscriptions and curse tablets from Roman Britain, as well as two inscriptions written on curse tablets at Bath in some form of Gallo-Brythonic using Latin script.

There are differing opinions about the success of Roman education and Latin literacy in Roman Britain, however. Some scholars point to the surviving texts of such churchmen as Patrick, Pelagius, Faustus and Gildas to demonstrate that their training was effective enough to enable them to write well and even earn the commendation of their peers. The Celt-Iberian poet Marcus Valerius Martialis bragged that there was a British audience for his Latin poems and in the second century the poet Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis celebrated the Romanization of the west by declaring that “eloquent Gaul has taught the Britons to be lawyers” (clearly referring to ability to plead cases in Latin). Excavations in 1973 at one of the military outpost along the northern border of Roman control reveals a set of wooden slates upon which soldiers wrote around the year 100 CE, usually called the “Vindolanda Tablets.” These were written in Roman cursive by a large number of different hands, demonstrating the spread of Latin literacy.

On the other hand, the number of texts and authors known from Roman Britain is fairly small. In most other Roman provinces wealthy citizens would erect monuments with Latin dedications declaring their good works publicly, but this does not seem to have become common in Britain: is this because so few people were literate in Latin? Does this indicate that the emphasis on literacy was low, or that the Celtic languages remained relatively strong? The majority of Latin inscriptions were produced by and for the militarized zones which might also emphasize a distinction between the local, settled population and the military population, many of whom were recruited from elsewhere in the empire and whose only common medium of communication was Latin.

Celtic Literacy in Ireland

The greatest stroke of genius amongst the Celts as far as literacy is concerned was the invention of ogam by speakers of Goidelic (i.e., “Irish” or “Gaelic”), although it is not yet clear whether ogam was invented in Britain or Ireland.

The ogam alphabet was inspired by exposure to the Latin alphabet, but was created specifically for the writing of short Gaelic inscriptions. It may have been devised by Irish colonists in western Britain during the Roman occupation, but it has also been suggested that the Irish kings of Brega (in Leinster, the eastern province of Ireland) may have devised it in imitation of the Roman practice of erecting stones with inscriptions which commemorated important leaders and the lands claimed by them. The ogam stones of Brega follow territorial boundaries very closely and coincide with evidence of contact with the Roman Empire. An ogam inscription near Slane seems to commemorate the historical leader Mac Cairthinn mac Coelboth, who was active in Brega in the late 5th or early 6th century.

There are a number of Gaelic-Latin bilingual inscriptions in western Britain, in ogam and Roman scripts. This suggests that the ogam was asserted to be a high-register script and Gaelic a language on a par with Latin. Probably the most interesting of these is the so-called “Vortipor(ius) Stone”, which may or may not refer to King Vortiporius of Dyfed. The Gaelic-Latin Knoc y Doonee Stone on the Isle of Man commemorates a man with a name showing Brittonic influence although his father’s name is Goidelic.

The earliest inscriptions are written along the edge of an object. Even early ogam stones often show contact with Christianity, such as the addition of an inscribed cross, such as the memorial stone at Drumconwell.

Although until the 1990s conservative estimates placed the era of the creation of ogham to the 4th-5th centuries CE, more recent scholarship has argued that the date should be pushed back to the 2nd to 4th centuries. An earlier date is supported by archaeological research in 1998-2000 at the Romano-British settlement of Silchester, far east of most contemporary Irish colonies in Britain. An ogham inscription on a small column from a building there indicates that it was part of the home of an Irish immigrant. The column was put into a well in the late fourth or fifth century, so the use of ogham must have been well established by this time.

The debt owed to Latin is obscured by an entirely different writing technique – a series of strokes in different directions – as well as native terminology for the alphabet and aspects of inscription and literacy. In fact, one tradition states that the ogham alphabet was named after and attributed to the native god Ogma, who was clearly related to the Gaulish god Ogmios described by Lucian. This demonstrates the degree to which the Gaels were able to fashion a solution to literacy on their own terms and within their own traditions, without having to borrow wholesale from Roman culture. Indeed, ogam seems to have retained a close association with paganism, in opposition to the Latin-based script and literacy advocated by the Christian church.