Celts, Art and “Celtic Art”

It is important to emphasize from the outset that there is no singular style or form for “Celtic art.” Just as different dialects and branches of Celtic languages evolved in different geographical and cultural contexts over space and time, so did different forms and varieties of artistic expression.

The most widely known form of Celtic art is the branches formally branded “La Tène” by archaeologists and art historians (explored in greater detail in this chapter). As has been emphasized in recent decades, however, it is a mistake to equate La Tène material culture with Celticity: not all speakers of Celtic languages produced or used La Tène-styled artifacts and the La Tène style was adopted by at least some people who did not speak Celtic languages exclusively. Celtic-speaking communities existed for centuries before the invention of the La Tène style and spread to geographical locales that the new art style did not reach, at least in significant quantity.

Although there is nothing wrong about searching out the origins of Celtic art styles among the civilizations of the mediterranean – the Greeks, Romans, Etruscans, and so on – earlier models and sources of inspiration should only be seen as that: points of departure. What is equally important is how an individual artist or artistic community makes selective and creative use of new stimuli and refashions it according to their local and contemporary aesthetics and context. All artists owe something to those who went before them: we could equally ask why they chose to ignore, elaborate, extend or exaggerate the creative potential of ideas and elements available to them.

The ideals of the representational art of the “Classical” world were not necessarily of importance to Celtic artists and their patrons. We should not see Celtic art (or the art of any other people) as an unsuccessful attempt at copying Classical models (or any which presumably try to depict the “real world”) but rather ask how any particular artistic style serves the needs of those who create and use it. This might entail an entirely different way of seeing and representing the world, seen and unseen, and of thinking about art and its social functions.

Although there is no singular explanation for the meaning or functions of Celtic art, one helpful way of thinking about it is in terms of the salient display of individual social status. Such art was labor-intensive and expensive to produce, so those who paid for such pieces were making a conscious effort to exhibit and highlight their ability to acquire and distribute resources, and hence their capacity for leadership. This is apparent in highly ornamented equipment used for rituals of feasting, such as the Brno Flagon or the Capel Garmon Firedog. It is also implicit in jewelry and other ornamented wearable items, such as the Bern Brooch.

On the other hand, some items are highly decorated with artistic detail that is not only difficult to see but is sometimes deliberating hidden from sight, such as on the backside of brooches meant to be worn. This indicates that the artwork and the figures in it were believed to have a religious or spiritual significance beyond a mere statement of artistic excellence or economic status.

Evolving Styles and Aesthetics

The artistic styles used to decorate items believed to have been created by Celtic-speaking communities developed over time in different locales. Some of these styles were widespread and long-lived, suggesting close ties and networks of exchange across distance. Others were limited in space and/or time, suggesting usage and meanings that did not “translate” well across communities.

Archaeologists and art historians have categorized these art styles and attempted to identify the times and places where they were used and had currency. The broad outlines of this taxonomy were defined by Paul Jacobsthal in his influential volume Early Celtic Art (1944) as:

- The Early Style (c.480-350 BCE)

- The Waldalgesheim Style (c.350-290 BCE)

- The Plastic Style (290-190 BCE)

- The Sword Style (190 BCE onwards)

Pre-La Tène Art of the Celts

Simple geometric patterns were used across Europe during the late Bronze Age to decorate items, whether of high or low status. Artifacts created by people presumed to be Celtic follow these artistic forms common at the time. A fine example of this is the decoration on the golden foil covering the dagger and shoes of the chieftain buried in the Hochdorf tumulus. These geometric patterns are echoed in a piece of cloth that also survived in the burial.

The Early La Tène Style

Exotic imports flowed from centers of Greek and Etruscan culture northwards inland into the “Western Hallstatt zone” – a broad geographical area from eastern France to Switzerland – during the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. This exchange network was enabled by the emergence of early urban centers, increasing overall material wealth, and heightened social hierarchies.

These imported goods and the artistic styles which embellished them provided the external stimulus needed to create a bold and innovative new art style. The La Tène art style seems to have emerged as more centralized socio-economic structures were broken up into a larger number of smaller communities in competition with one another. Artistic expression may have been a means for the élite of these communities to assert their role as social leaders able to acquire and distribute wealth and power. La Tène artifacts appear particularly oriented around three kinds of social activity:

- Feasting and drinking

- Warfare and the assertion of military might

- Assertion of personal social status

Artifacts bearing variations of the La Tène style seem to appear in numerous places at the same time, failing to betray any singular point of origin. This suggests an extensive and well-connected social network of artisans and craftsmen creating a new vocabulary for expressing cultural achievement and social prestige by drawing creatively from the artistic potential of external models, while simultaneously inventing something consciously distinct from them.

Two motifs derived from the classical repertory are recurrent, the palmette and the lotus. The essence of the La Tène style, however, is not the slavish imitation of classical designs, but their adaptation into a new and vibrant treatment that progressively becomes more assured and independent of any debt to the original source. This is achieved initially by breaking up the classical motifs into their component elements, and re-assembling them in a different composition. (Harding, The Archaeology of Celtic Art, 42)

Exchange with the classical mediterranean world also had the effect of exposing Celtic artisans to the potential of new materials, especially coral, ivory and silk.

The artwork of Celtic peoples – from La Tène on – frequently features stylized heads and faces, sometimes so ambiguous or abstract that they are hard to recognize. Only infrequently does the artwork of Celtic peoples include entire human bodies in representational styles. This demonstrates that artists were capable of producing such depictions and that it was a conscious aesthetic decision not to do so.

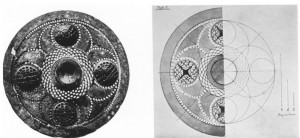

The phalera (horse harness ornament) found in a warrior’s burial at Somme-Bionne, dated to the beginning of the Early La Tène phase (450 BCE to 400 BCE) demonstrates the precise use of the compass to create complex geometric designs (above), sometimes in semi-organic, floral form. The effect relies upon the overlap of a series of nine concentric circles from the center outwards.

The wine flagons found at Basse-Yutz in eastern France, dated to sometime between 400 BCE and 360 BCE, illustrate this local adaptation of foreign influences and materials. The shape of the flagons is based on that of Etruscan jugs that were imported into the region, and the style of the coral inlays that decorate the flagon also point towards Etruscan models. There are human faces that adorn the handles of the flagons which appear to be based loosely on Etruscan art, but the shape of the face and its features have been stylized in a non-Etruscan manner.

An Inventory of Artistic Motifs

The following chart provides an inventory (not claimed to be exhaustive) of the most common artistic motifs used in Celtic art, with brief notes about each, in roughly chronological order.

Lotus-flower petals: Likely inspired by the ornamentation on imported Greek artifacts, but broken down to the simplest element and rearranged in new forms, such as wave patterns, similar to patterns characteristic of the Hallstatt art style. Its use on Celtic artifacts can be dated to c.400 BCE.

Lotus-flower petals: Likely inspired by the ornamentation on imported Greek artifacts, but broken down to the simplest element and rearranged in new forms, such as wave patterns, similar to patterns characteristic of the Hallstatt art style. Its use on Celtic artifacts can be dated to c.400 BCE.

Ring-and-dot: A widely-used motif which is not exclusively Celtic. It is apparent by 400 BCE on Celtic artifacts.

Ring-and-dot: A widely-used motif which is not exclusively Celtic. It is apparent by 400 BCE on Celtic artifacts.

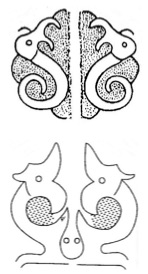

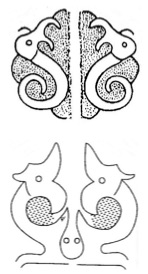

Symmetrical dragon/griffin pairs: This elaborate motif is associated with La Tène material culture, emerging by the late 5th BCE. It may be ultimately derived from the “Lady of the Animals” emblem, but the design was constantly altered and became increasingly abstract. Hundreds of examples of this symbol have been found on sword scabbards across the Celtic world, especially in continental Europe.

Symmetrical dragon/griffin pairs: This elaborate motif is associated with La Tène material culture, emerging by the late 5th BCE. It may be ultimately derived from the “Lady of the Animals” emblem, but the design was constantly altered and became increasingly abstract. Hundreds of examples of this symbol have been found on sword scabbards across the Celtic world, especially in continental Europe.

Wave tendrils: Commonly used in “Waldalgesheim-style” art (named after the lavish tomb of an élite female), it seems to emerge in Celtic art c. 380 BCE to c. 300 BCE. These jagged wave-tendrils are uniquely Celtic: Greek tendrils flowed gently in one direction only; each forward-moving wave in the Celtic wave- tendrils is disrupted by a counter movement, creating an unsettling impression.

Wave tendrils: Commonly used in “Waldalgesheim-style” art (named after the lavish tomb of an élite female), it seems to emerge in Celtic art c. 380 BCE to c. 300 BCE. These jagged wave-tendrils are uniquely Celtic: Greek tendrils flowed gently in one direction only; each forward-moving wave in the Celtic wave- tendrils is disrupted by a counter movement, creating an unsettling impression.

Pelta/palmette: These appear on Greek vases of the 4th century BCE to depict the profile view of Thracian shields and were likely the inspiration for Celtic artists. They became ubiquitous in later Iron Age Celtic art in many guises.

Pelta/palmette: These appear on Greek vases of the 4th century BCE to depict the profile view of Thracian shields and were likely the inspiration for Celtic artists. They became ubiquitous in later Iron Age Celtic art in many guises.

Diagonal tendril pattern: This is a widespread element in Hungary and popular in the Carpathian Basin, dated from at least 250 BCE. It is mostly to be found engraved on sword scabbards.

Diagonal tendril pattern: This is a widespread element in Hungary and popular in the Carpathian Basin, dated from at least 250 BCE. It is mostly to be found engraved on sword scabbards.

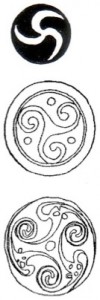

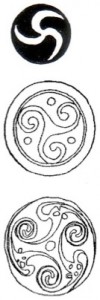

Triskele (three-limbs with many variations): This is not not an exclusively Celtic motif: it is prominent in the Roman world and other cultures as well. The simplest variation of the motif appears in Atlantic Neolithic art, well before the Celtic era. It appeared intermittently in Iron Age Celtic art and has a variety of variations in Roman-British Art. Its most notable appearance is on a series of disc brooches dated to around the 2nd to 4th centuries CE. Trumpets sometimes make up the inner limbs of the triskele. Simple triskeles were fairly widespread in earlier Iron Age art in Britain, but more sophisticated symbols involving trumpets were developed for stamped mounts for caskets in the 1st century CE.

Triskele (three-limbs with many variations): This is not not an exclusively Celtic motif: it is prominent in the Roman world and other cultures as well. The simplest variation of the motif appears in Atlantic Neolithic art, well before the Celtic era. It appeared intermittently in Iron Age Celtic art and has a variety of variations in Roman-British Art. Its most notable appearance is on a series of disc brooches dated to around the 2nd to 4th centuries CE. Trumpets sometimes make up the inner limbs of the triskele. Simple triskeles were fairly widespread in earlier Iron Age art in Britain, but more sophisticated symbols involving trumpets were developed for stamped mounts for caskets in the 1st century CE.

Trumpet: This motif can also be found in Roman art. It is found on Celtic artifacts from c. 165 to c. 256.

Trumpet: This motif can also be found in Roman art. It is found on Celtic artifacts from c. 165 to c. 256.

Confronted trumpet pattern: This motif can be found in trompetenmuster ornaments (openwork objects, such as horse-harness mounts, with trumpet shapes) across the Roman Empire. Artifacts using it have been dated 165-256 in some parts of continental Europe, although it became common in the native art of Scotland and Ireland.

Confronted trumpet pattern: This motif can be found in trompetenmuster ornaments (openwork objects, such as horse-harness mounts, with trumpet shapes) across the Roman Empire. Artifacts using it have been dated 165-256 in some parts of continental Europe, although it became common in the native art of Scotland and Ireland.

“Durrow” or triskele spiral: This motif is present but not common in Romano-British art. It became of major importance in early medieval Insular Celtic art.

“Durrow” or triskele spiral: This motif is present but not common in Romano-British art. It became of major importance in early medieval Insular Celtic art.

Ying-yang: This motif is present but not common in Romano-British art. It became of major importance in early medieval Insular Celtic art.

Ying-yang: This motif is present but not common in Romano-British art. It became of major importance in early medieval Insular Celtic art.

Class Discussion

Try to identify all of the elements above on a Celtic artifact, such as the Agris Helmet. How closely can you date an artifact from the presence or absence of these motifs?

Regional Distinctions and Developments

When considering the definition of Celtic art, its evolution through time, its distribution through communities across Europe, and the implications of these phenomena, it can be helpful to consider each local separately, to see how particular styles, techniques, materials and artifact types spread and develop.

Britain

The earliest surviving artifacts bearing forms or art styles that can be meaningfully classified as “Celtic” date as far back as the fifth century, although, as in the case of the emergence of the La Tène form, exact origins and innovative centers are extremely difficult to pin down. The Megaws have recently contended that items engaged in the earliest forms of La Tène can be found in Britain – brooches, swords, scabbards, and decorative items – and many of them are local adaptations of Continental models:

Britain appears early – that is already perhaps in the fifth or four century – to have started its own variations of basically La Tène A brooch forms … Certainly we can with some confidence continue to suggest that the beginning of a fully Insular style did not occur before the earlier third century BC and that this was preceded by a phase of experimentation … (Megaw and Megaw, “A Celtic mystery: some thoughts on the genesis of insular Celtic art”)

One of the earliest identified fragments of such early artifacts is the fragmentary remains of part of a bronze vessel found in Cerrig-y-drudion, probably the rim. The lyre-palmette ornament parallels styles on the continent, yet the use of “hatching” on the piece’s background suggest that it was produced locally.

Another early example is the Kirkburn sword, deposited into a burial in Yorkshire after it had already been used for some time. Its scabbard is engraved with tendril and leaf decoration, with red glass at its end.

Apparently unique to the British Celts is the decorated bronze mirror and an associated art style engraved onto the back of these items. They were produced from the late 2nd century to the middle of the 1st century CE, and employ a variety of geometric forms (mostly roundels and lyres) and hatching (for color/texture) to effect very elaborate ornamentation. Two of the finest examples are the Desborough Mirror and the Aston Mirror.