Contents

- Conquest and Supplantation

- Norman Invasions and Feudalism

- Wales

- Ireland

- Scotland

- Brittany

- References

Conquest and Supplantation

Ethnocentrism — judging the world from the perspective of a single society, usually with the assumption that it is superior to others — is a commonplace of all human societies; it may well have been a psychological necessity of group survival. All around the world peoples give themselves names which mean “the people,” see themselves as living in the centre of the world, and believe themselves to be the chosen favourite of god(s). Given the contrastive nature of ethnicity, and the conceptual precedent of the civil-savage dichotomy, people will often perceive themselves to be more fully human than their neighbours, whom they perceive as the “Other.” Such ethnocentric tendencies do not explain or justify all forms of domination and control, however: different political infrastructures and ideologies bring about specific sorts of relationships between different social groups.

There are many possible outcomes when two societies come into contact. When the two meet on equal terms, they can exist together for long periods of time, exchanging goods and people (the Peer-to-Peer relation illustrated on the left above). It is almost inevitable that material items and concepts will be exchanged between them, along with the words that describe them. They will also consciously coin words and develop artifacts which continue to maintain their distinction from other groups. Such strategies enabled the emergence and coexistence of massive numbers of languages and cultures around the world before the conquests of early modern European empires.

In the ancient world, a society stronger than a neighbour often forced it to acknowledge deference by making it pay tribute on a regular basis. Although this relationship of dominance might be enforced by violence or the threat of force, the dominant society usually did not meddle in the internal affairs or the cultural makeup of the subject culture.

When a group of people from one society move into the domain of another and retain their original distinctive ethnic identity they may form a colony (in the limited sense of a group resettlement). This is often referred to as a settler society. It is possible for the settler colony to offer services, goods, and intellectual capital without either host or settler being, or feeling, threatened by the other’s existence.

Settler societies can be, on the other hand, the first foray of an empire toward colonization. An empire is a state that imposes its authority on foreign peoples and territories. Empires emerged in the ancient world in such diverse locations as China, Peru, Persia and Egypt. A number of military strategies and socio-political arrangements have been used to initiate expansion and maintain control of subject peoples. Beyond whatever material conditions existed and were employed, grand narratives of “civilization,” which provide a pretext for the domination of the imperial culture and its authority, are integral components of the enterprise:

Neither imperialism nor colonialism is a simple act of accumulation and acquisition. Both are supported and perhaps even impelled by impressive ideological formations that include notions that certain territories and people require and beseech domination, as well as forms of knowledge affiliated with domination: the vocabulary of classic nineteenth-century imperial culture is plentiful with words and concepts like “inferior” or “subject races,” “subordinate peoples,” “dependency,” “expansion,” and “authority.” Out of the imperial experiences, notions about culture were clarified, reinforced, criticized, or rejected. (Said, Culture and Imperialism)

The grand narrative of imperialism — that inherently superior civilizations are compelled to conquer and reform lesser ones — is a very old one, resting, as it does, on ethnocentric biases. Colonialism is the opposite end of this experience, namely, the political, economic, and cultural penetration of a subject people by an imperial power.

The imperial élite of ancient empires did not always want to wipe out the population of subject peoples entirely: they were instead exploited to add to the wealth and power of the empire in ways that land by itself could not. Modern empires have been much more interested in dispossessing native populations and replacing them with colonists. There is a common set of means and strategies by which supplanting societies have achieved conquest and dominance: “The arrival of interlopers inevitably sets off a prolonged and multilayered process, as they attempt to supplant the hold that prior occupiers have enjoyed over the land, perhaps for millennia, and establish superior links of their own.” They

- establish a “legal” claim to land by making symbolic and ideological acts (planting flags, writing charters and grants, etc).

- justify their occupation with a strong sense of moral superiority which is also associated with and justified by a claim of superiority in civilization and culture.

- explore the territory, create representations of territory “owned” by supplanters (ie, maps), and catalogue the resources for exploitation.

- name places in their own language, image and order, helping to make the foreign make it feel familiar and knowable.

- establish military forces to defend the territory against rival claimants, including the natives.

- develop foundation stories to invest themselves with a strong sense of connection to the territory.

- develop the resources of the territory, particularly through cultivation, in ways that are supposedly superior to those of the pre-existing people.

- populate the place in such numbers that the supplanters feel secure in their occupation. remove the original inhabitants, whose presence otherwise provides a potential challenge to their occupation.

Class Discussion

Be prepared to discuss now and in future units how these strategies were implemented in the expansion of Anglo-Norman/English colonies into Celtic communities.

Norman Invasions and Feudalism

From French-Normans to Englishmen

William II became the Duke of Normandy in 1035 and invaded England in 1066 to pursue his claim for the English kingship. His victory at the Battle of Hastings (after which he became known as “William the Conqueror”) allowed him to replace key members of the English élite with his own loyal retainers, ushering in a generation or two of Norman-French dominance over English culture. The division between Anglo-Saxon and Norman-French was initially stark, and the effect on the English language is still evident to this day (many low-register words are derived from Anglo-Saxon, while high-register words with a similar meaning are derived from French).

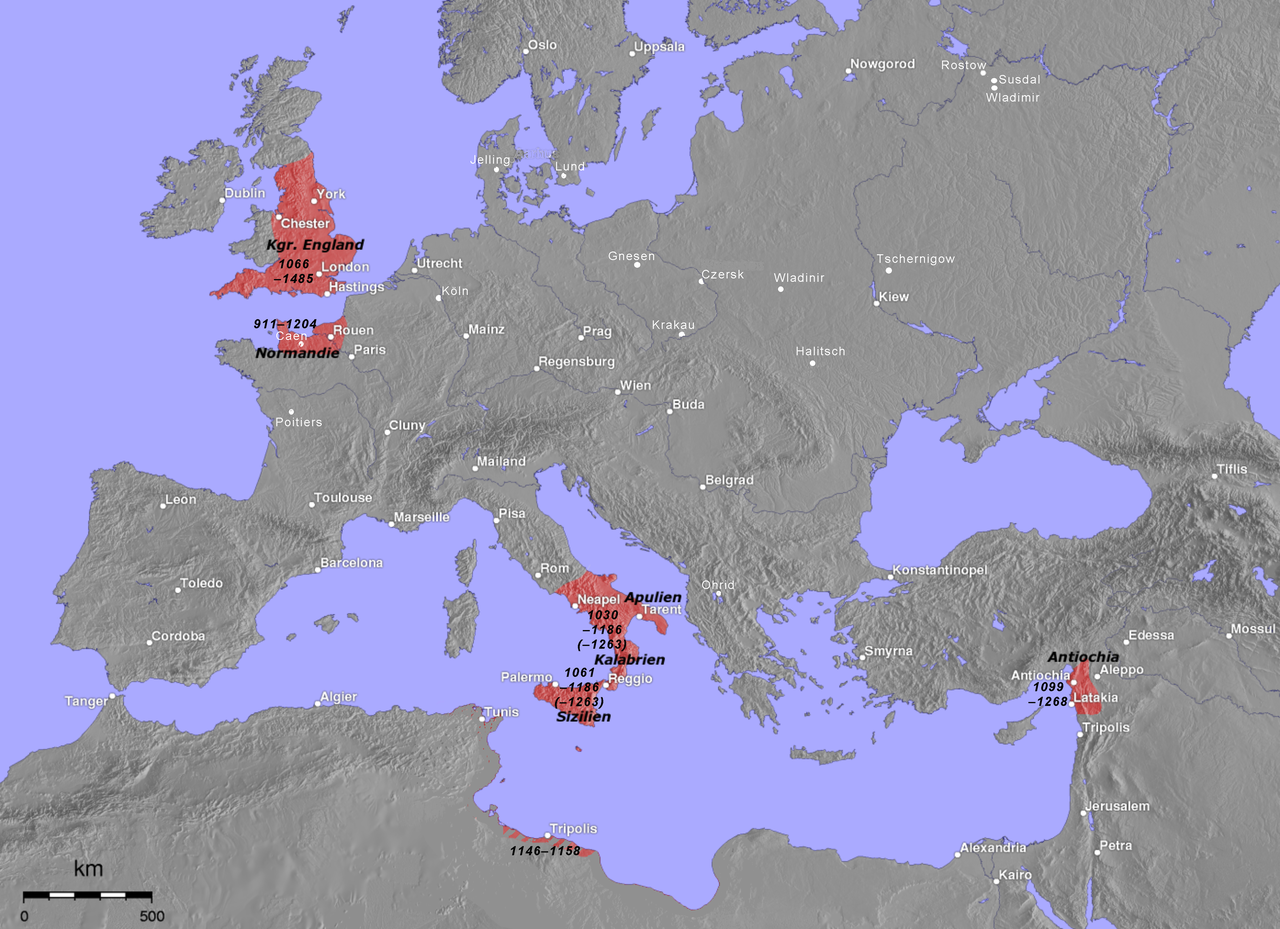

As in other parts of Europe where the Normans gained dominance (see map above), the French language and Norman-French culture were seen as signs of refinement and culture. The Norman invasion came to be represented as a civilizing force on Anglo-Saxon society, rather than being in opposition to it. The result was that by 1130 x 40, even the French-speaking élite in England, some descended from the Norman invaders, came to see themselves as essentially English.

French-speakers living in England [in 1140] could see the Anglo-Saxon past as their past. The king and a tiny handful of the very greatest magnates, holding vast estates in Normandy as well as England and Wales, may have thought of themselves primarily as Frenchmen, but the overwhelming majority of the landowners of England knew that they were English, French speaking, of mixed ancestry – as William of Malmesbury was – (usually French on their father’s side and proud of their forefather’s achievements) – but English even so. (Gillingham, “The Beginnings”)

Inferiorizing the Celts

The sense of the superiority of Anglo-Norman culture, as a pinnacle of human achievement, over that of Celtic neighbours was legitimated and reinforced by the 12th-century “rediscovery” of Greek and Latin texts which expressed the opposition between civilization and barbarism, as developed and used in Antiquity (the classical Greek and Roman worlds). Whereas previously the major fault line in medieval Europe was between pagan and Christian (as we saw in the Viking era), the new division was asserted to be between civilized and uncivilized-savage.

A particularly important and influential text in the formulation of Celtic inferiority was William of Malmesbury’s 1125 Gesta regum Anglorum “Deeds of the kings of the English.” This volume of English history was highly regarded and popular, and it depicted “English history as a progress from barbarism to civilisation,” a pattern William claimed to be evident as early as the 6th-century marriage of King Ethelbert of Kent to the Frankish princess Bertha. By contrast, he casts the Celtic peoples of Ireland, Scotland and Wales into the role of unrefined barbarians of a distinctly inferior status. This example was taken up and developed by other Anglo-Norman authors of the 12th century, such as Geoffrey Gaimar and Gerald de Barri of Wales, who emphasized a number of stereotypes, claiming that Celtic peoples:

- are animal-like, lacking proper physical, moral and cultural boundaries between the human and animal worlds

- are lazy, unwilling to engage in sustained labour

- are incapable of imposing human culture on the wild; this implicated domesticating the landscape as well as their own base, animal nature

- are outside the bounds of Christian decency and moral codes, engaging in indecent sexual norms and levels of violence

These biases colour the depictions of encounters between Anglo-Normans and Celtic peoples from the 11th century onwards and are at the core of the political ideology legitimating the conquest of Celtic society, namely, the Anglo-Normans’ belief that they were an inherently superior culture, worthy of ruling over inferior societies that they will “civilize” through their imposition of new social and cultural norms. These prejudices discouraged the hybridization between Celtic societies and the colonies of Englishmen/Anglo-Normans who settled within them and reinforced the conceit that colonists should remain pure and loyal to the imperial authority and cultural standards, lest they be contaminated by the inferior peoples around them.

The dominance of Anglo-Normans in Britain was not achieved solely through military might, but by the conspicuous display of the trappings of feudal culture in the royal courts of England and Scotland. The impact of the Anglo-Normans was greater than their numbers because they were associated with a cosmopolitan and international movement with political, social, economic, and religious dimensions which local élites aspired to emulate. Such was the vogue that an English chronicler remarked in the thirteenth century, probably over-emphatically, that “more recent kings of Scots profess themselves to be rather Frenchmen, both in descent and in manners, language and culture; and after reducing the Scots to utter servitude, they admit only Frenchmen to their friendship and service.”

Wales

William the Conqueror was not immediately concerned about the conquest of Wales; instead, he delegated the task to three Norman lords: Hugh d’Avranches (Earl of Chester), Roger de Montgomerie (Earl of Shrewsbury), and William FitzOsbern (Earl of Hereford). Conquest in the more mountainous and inaccessible regions of the north and west proved elusive, so they concentrated on the more fertile, low-lying areas of the south and east.

Boroughs (urban centres with specially granted privileges) were built alongside the Anglo-Norman strongholds and filled with English and Flemish settlers, especially in the Marches. The Welsh economy developed rapidly by the rise of boroughs and the domestication of the landscape for agriculture: the percentage of the population of Wales living in towns went from zero to 10%. This near monopoly of wealth and power in the anglicized towns, however, initiated the marginalization of Welsh language and culture.

The Norman lords also attempted to impose their church reforms, and the authority of the English church, upon the Welsh. Welsh monasteries were dismantled and handed over to orders in England and France. The Benedictines acted to extend the colonial interests of the Anglo- Normans in Wales and extract profit for them from the Welsh peasantry, but the order of Cistercians who settled in Welsh Wales were not long in assimilating to Welsh society and acting in its interests. Bishop Urban of Llandaff was willing to compromise the independence of the Welsh church by submitting to the superiority of the Archbishop of Canterbury, but Bernard of St David’s resisted these pressures.

The Welsh scholar Rhigyfarch, based at the monastery of Llanbadarn (near modern Aberystwyth), who also wrote the Life of St. David, expressed the cultural humiliation that accompanied the political subjugation of Wales in an account in Latin:

Now the works of earlier days lie despised; the people and the priest are despised by the word, heart, and work of the Normans. For they increase our taxes and burn our properties. One vile Norman intimidates a hundred natives with his command, and terrifies (them) with his look. Alas the fall of our former state, alas the profound grief: it is not possible to leave, nor even possible to stay. […] O (Wales), you are afflicted and dying, you are quivering with fear, you collapse, alas, miserable with your sad armament. Nothing is (now) joyful, nothing pleasant. Your beard droops, your eye is sad. An alien crowd speaks of you as hateful. See how ignominy fills the open face with disgrace.

Gruffudd ap Cynan (aka Gruffydd ap Cynan, c.1055-1137) was a member of the royal dynasty of Gwynedd, although he was born in Dublin after his father fled to Ireland. Gruffudd landed on the island of Anglesey with soldiers from Norse Dublin in 1075 to take the throne of Gwynedd from a rival who had just claimed it. Gruffudd also made use of soldiers lent by the Norman lord Robert of Rhuddlan.

After successfully taking the rule of Gwynedd from Trahaearn, he went on to recover Welsh lands from Norman lords in the east, even attacking Rhuddlan castle. After a mutiny by his Norse-Irish retainers, Gruffudd was pushed out of Gwynedd. In all, Gruffudd was ruler of Gwynedd four separate times, each time regaining the throne after being forced out by enemies. His last reign began in 1099 and continued until his death in 1137. This period marks a rebound in the fortune of Welsh rulers as they attempt to regain territory and powers lost to the Norman Marcher lords.

By the mid-12th century, Wales was effectively divided into two distinct zones: the Welsh Marches (in red on map above), under the domination of the Norman Marcher lords, and the Principality of Wales (aka Welsh Wales) in the west, ruled by native Welsh leaders. The Marcher lords passed on their positions to their own heirs, were not bound by English common law, and operated semi-independently of the King of England, sometimes even defying his authority. Marcher lords were eager to marry Welsh princesses to help legitimate their rule, but some native Welsh rulers were equally willing to have their children married to them in hopes of enhancing the family’s access to power.

Gruffudd’s son Owain (often called “Owain Gwynedd”) inherited the rule of Gwynedd in 1137. His ambitions were reflected in the title he claimed: “Prince of Wales.” Owain built upon the foundations laid by his father, consolidating Gwynedd and fortifying it against the encroaches of the Marcher lords and defending Wales against invasions by Henry II of England. He rejected the Anglo-Norman candidates for Bishop of Bangor (overseeing Gwynedd) suggested by Archbishop Thomas Becket of Canterbury and installed his own. He ruled until his death in 1170.

Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (aka “Llywelyn the Great”) was a grandson of Owain Gwynedd, born c.1172. He seized the rule of Gwynedd by 1200 and signed a treaty with King John of England, submitting to him as a vassal. Llywelyn married John’s daughter in 1205 and took advantage of this relationship to take over Powys when its ruler was arrested by John. Llywelyn made alliances with other Welsh rulers and after King John of England was forced to sign the Magna Carta in 1215, he made concessions to Llywelyn which made him effective overlord of Welsh Wales (see yellow and grey areas on map above). He remained the dominant ruler in Wales, making treaties with Welsh rulers and Marcher lords, and intensifying the supremacy of Gwynedd over the other provinces, until his death in 1240.

King Henry III of England ensured that Gwynedd, and all of Wales, suffered humiliation and instability after the death of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth. Wales regained some of its liberties under his grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (aka “Llywelyn the Last” or “Llywelyn II”), born c.1223. Llywelyn opposed his brothers Owain and Dafydd, who had submitted to Henry III, defeating them in 1255 at the Battle of Bryn Derwin. He then claimed the throne of Gwynedd and began to reclaim lands that the English king had shaved off of it, making alliances and taking advantage of the unpopularity of English rule.

By March 1258, Llywelyn’s supremacy in Wales was acknowledged by nearly all of its native leaders and he took for himself the title “Prince of Wales.” Llywelyn did his best to take advantage of the vulnerabilities of King Henry when the English king was defeated by rivals in 1264. He stood at the summit of his achievements in 1267, when Henry signed the Treaty of Montgomery, which acknowledged Llywelyn as prince of the province of Wales. (On the map above, Llywelyn’s original kingdom, Gwynedd, is in green; the kingdoms of his vassals are in blue; the kingdoms that he took by force are in purple.)

Henry’s son Edward I, however, was a brutal autocrat determined to conquer and subjugate all of Britain and exercised a keen sense of military and political strategy to do so. Llywelyn drew the ire of Edward by disregarding his obligations to pay him tribute and homage, neglecting to answer to his summons, and marrying the daughter of Edward’s enemy Simon de Monfort, Eleanor. Thus provoked, Edward kidnapped Eleanor in 1275 and spent the next five years plotting against him, stirring up dissent against him and building a series of castles in Gwynedd held by his loyal vassals. In desperation, Llywelyn led a national rebellion that was eventually cornered by Edward on the island of Anglesey. The Archbishop of Canterbury, John Pecham, was assigned to arrange a settlement, but Llywelyn remained defiant to the anglocentric churchman. The Welsh council produced a document in response to the crisis on 11 November 1282, complaining that Edward had broken his treaties with the Welsh and that he

exerts a very cruel tyranny over the churches and ecclesiastical persons. […] Likewise the people of Snowdon say that even if the [Welsh] prince were willing to give their land to the [English] king, they would nevertheless be unwilling to do homage to a stranger whose language, customs and laws are totally unknown to them.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was probably betrayed and assassinated on 11 December and his brother, Dafydd, was captured. He became the first Welshman to be hanged, drawn and quartered in England. Both of their heads were displayed at the Tower of London.

King Edward reduced Wales to a subservient principality of England and ensured the Welsh were aware of the humiliation of defeat and subjugation: a Welsh annalist said of these events that “all Wales was cast to the ground.” Edward removed or destroyed the national symbols of Welsh sovereignty: the skull of St. David was taken to the Tower of London, the cross-shaped reliquary worn by Welsh princes was taken to Windsor Castle, and the seals of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd were melted down.

Edward enacted the Statutes of Wales (aka Statutes of Rhuddlan) in 1284: “[The land of Wales has come] into the lordship of our possession [and has been] annexed and united to the crown of the said kingdom as part of the said body.” This legislation also redrew and redefined county boundaries in Wales, imposed English common law for all criminal cases, arranged for the collection of taxes, set up administrative and legislative offices, and enabled the king to directly appoint officials in Wales. These laws remained in effect until Henry VIII’s Laws in Wales were enacted in 1536, although no initial efforts were made to interfere with the internal affairs of the Marcher Lords.

After the English conquest, Welsh natives were dispossessed from some areas and relocated to poor, unwanted land to make room for further settlements of English colonists. These latter were often given special privileges, rental rates, and subsidies denied to the Welsh natives. The boroughs generally became English-(language)-only zones where Welsh monoglots were effectively barred from gainful service. The posts of greatest power and advantage were reserved for English appointees. Such disparities ushered in the marginalization of the Welsh language and culture.

Class Discussion

What does the Welsh Chronicle Brut y Tywysogion 1091-4 indicate about Welsh perceptions of the Norman invasions and the contest over Welsh territory?

What does Gerald De Barri (of Wales), Description of Wales §1.8, 2.8, 2.10 say about Welsh military practices and their attitudes regarding the invasions of their country? How is the “Heroic Ethos” reflected in these passages?

Ireland

Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair (anglicized as “Rory O’Connor”) became King of Connaught in 1156. He became the high-king of Ireland in 1166 and was on the verge of cementing national unity in 1167 when unexpected events unsettled Irish politics.

Diarmait Mac Murchada (anglicized as “Dermot MacMurrough”) had been the provincial overking of Leinster since 1132. He had control of the powerful fleet of Norse Dublin and had rented them to Henry II of England for six months as he subdued Wales in 1165. When his ally Muirchertach Mac Lachlainn was killed in 1166, Diarmait was exposed to the wrath of Ruaidrí Ó Conchobair. Ruaidrí’s ally, Tighearnán Ó Ruairc of Bréifne, humiliated Diarmait by forcing him to submit, surrender hostages, and then leave his office; Tighearnán was settling the score for Diarmait’s kidnap of his wife, Dearbhfhorghaill of Meath, in 1152. Diarmait fled to the Anglo-Norman king Henry II, asking him to return his favours.

Henry was not ready to commit his own resources to campaigning in Ireland, but he received Diarmait’s homage and fealty and allowed his vassals in Britain to join Diarmait in regaining his throne in Leinster. Diarmait, for his part, mustered powerful lords of the Anglo-Norman order, some of whom had estates in Wales, with promises of rewards in Ireland: to Richard de Clare, earl of Pembroke (later known as “Strongbow”), he gave his daughter in marriage and the province of Leinster as an inheritance; to Welsh-Norman lords Maurice FitzGerald and Robert FitzStephen, he promised Wexford and two adjacent regions.

Diarmait’s new Anglo-Norman allies overwhelmed Leinster between 1169 and 1171; not only this, but they attacked Meath and Bréifne, the kingdom of Diarmait’s enemy Ó Ruairc. Henry II insisted that de Clare desist from these extreme and unapproved activities when he realized the magnitude of his vassals’ ambitions in Ireland. Diarmait died in 1171 and de Clare assumed power in Leinster, vanquishing an attempted Irish insurrection against him. The Irish appealed to Henry II for help and the English king comprehended the dangers of warlords operating independently so near his own kingdom. When he headed a fleet in 1171, landing in Waterford, de Clare immediately apologized and submitted to him. Henry granted the province of Leinster to him for his loyalty, and travelled Ireland receiving submission, hostages and promises of tribute from the other major kings, who saw Henry’s supervision preferable to the unrestrained rapacity of the Norman barons.

Henry II convened the Synod of Cashel of 1172 to initiate the reform of the church in Ireland according to English standards. Not only did Pope Alexander III give his blessing to the conquest, he insisted that Irish bishops excommunicate any chieftains who broke their oaths of fealty to the English king.

The Anglo-Norman barons, using archers drawn from their Welsh estates, were aggressive and surprisingly effective in their military advance across Ireland, despite lacking support from the King of England. The protracted and sustained struggle encouraged the Gaels to respond in the development of a professional class of mercenaries, the gall-óglaigh “young foreign warriors” (anglicized as “gallo(w)glasses”) who were not tied to specific estates or agricultural labour.

Provincial Irish kings willing to comply with the demands and rule of the English king preserved a modicum of Gaelic independence in some areas and prevented the forfeitures that would have allowed the expansion of Norman colonization to the mid-13th century. Some Irish kings even attempted to curry favour with the king by contrasting their own submission to him with the unruliness of the Norman barons.

Although a series of revolts under Gaelic kings in the mid-13th century unsettled the English colony in Ireland, the Anglo-Normans were still expanding the areas under their control. An alliance between Brian Ó Néill, Aodh Ó Conchobhair, and Tadhg Ó Briain declared Brian to be the high-king of Ireland in 1258, but he was defeated by colonists at the Battle of Druim Dearg in 1260 and killed in action. Thereafter, no Gaelic leader attempted to claim the high-kingship.

The Gaelic experience of invasion of and wars with the Vikings had a strong influence on the ways in which the Anglo-Norman invasions were understood: like the Vikings, the Anglo-Normans were commonly perceived of and described as Goill or even Danair “Danes,” in opposition to the native Gaels of Ireland.

Scotland

Native and Norman

At the time of the Norman invasion in England, Gaelic was at its high-water mark across Scotland: it was the tongue of the courts of the king and most of the native élite; it was used by church clergy and national intelligentsia; it was spoken in communities in the south of Scotland, and even south of the Tweed. The battle-cry of Scottish soldiers in 903, 918 and 1138 was “Albanaigh, Albanaigh!” [Gaelic for “Scotsmen, Scotsmen!”].

Many English nobles refused to submit to William the Conqueror and some sought refuge in the Scottish court. King Malcolm III (also known as “Malcolm Canmore,” whose reign was 1058–93) married the young princess Margaret, daughter of Anglo-Saxon prince Edward and Hungarian princess Agatha; she had been exiled from England with her brother in 1072. While she did show some support for existing Gaelic institutions, Margaret disliked many practices she found in Scotland and attempted to alter them according to the cultural standards of her English and continental background. She set a number of church reforms into motion, including the resettlement of Benedictine monks from Canterbury in Dunfermline.

The floodgates of change opened dramatically under the rule of David I, the youngest son of Malcolm Canmore and Margaret. David had been raised as a hostage in the French-speaking court of Henry I, the son of William the Conquerer, and was said to have been a paragon of Norman knighthood. David had ruled as “the prince of the Cumbrian region” (Strathclyde, Tweeddale and Teviotdale) during the reign of his older brother Alexander I. David initiated that broad range of political, economic and religious reform referred to as feudalism (explained further in the next unit) in Cumbria. He attempted to extend these developments throughout Scotland after he ascended to the throne in 1124, relying heavily upon the foundations he established first in Cumbria.

Some of the native Gaelic élite themselves were quick to adapt to David’s innovations. The MacDuffs, a leading Gaelic kindred in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, were granted the earldom of Fife by David c. 1136 as well as positions as national justiciars. This may have encouraged other Gaelic leaders to accommodate themselves to the new order. In fact, up to the first War of Scottish Independence (c. 1290), seven of the thirteen ancient earldoms of Scotland remained in the hands of native families, and four of the others had come into Anglo-Norman hands by marrying into native families.

Nonetheless, the impact of the Anglo-Normans was significant. From David’s reign to the end of the reign of Scottish king William I (1165–1214) the native élite in some areas were dispossessed in favour of incomers. Extensive grants to Anglo-Norman lords forming a circle around Galloway look like a deliberate strategy of containment. A similar pattern appears in the land grants of the Firth of Clyde, controlling access to the Gaelic west, given to the Stewarts and others.

About fifteen burghs were founded during David’s reign (1124–1153), largely populated by Flemish immigrants. William “the Lion” later granted the first burghal charters. Most Scottish burghs were in the south and east, where they had access to natural resources and sea routes where they could trade with the continent of Europe. By the mid-fourteenth century burgesses were represented inside the Scottish Parliament alongside the church and the nobility, making them one of the “three estates.”

The economic and political importance of burghs gave them a greater prestige than the Gaelic-speaking countryside. Besides coming to sell raw materials and buy finished products, Gaelic speakers came to the burghs for employment, not least because the high mortality rate in towns from disease, fires, and warfare kept the demand high. As in Ireland, the foreign Anglo-Normans were referred to as Goill by the Gaels of Scotland (the more specific ethnonym Danair did not seem to take hold)

Class Discussion

What does the text by pseudo-Fordun, “On Highlands and Lowlands,” reveal about the changing ethnic identities and allegiances in Scotland?

Gaelicizing the Norse in the West

The Uí Ímair dynasty created a political and cultural infrastructure that soon connected Gall-Ghàidheal communities throughout the Irish sea and North Atlantic region and helped to re-establish Gaelic language and culture.

The Gall-Ghàidheal Somerled (Gaelicized as “Somhairle”), married to the daughter of the king of the Isle of Man, first appears on record in 1140 with the title regulus “king” of Kintyre. When in 1153 both David I (king of Scotland) and Olaf (Gaelicized as “Amhlaibh”), king of the Isle of Man, died, Somerled seized the opportunity to extend his rule and by 1158 he controlled territory from the north of Lewis to the south of Man. Despite his Norse connections, Somerled has been remembered in oral tradition to the present day as the hero who liberated the Gaelic west from the Vikings.

After Somerled’s death in 1164, his territories were fragmented between three of his sons and the sons of his brother-in-law, Godred son of Olaf of the Isle of Man. For several generations these leaders vied for supremacy and split nominal allegiances between the king of Norway and the king of Scotland. King Hakon of Norway mounted a naval expedition in 1263 to re-establish his control of the Hebrides, but failed. The last king of the Isle of Man died in 1265 and in 1266 Hakon’s son Magnus signed the Treaty of Perth, which formally ceded the Hebrides to the Scottish kings. Apart from the Northern Isles and the tip of Caithness, the Norse were absorbed into Gaelic society and are remembered in Gaelic tradition by their own descendants only as the alien “Other,” the archetypal enemy. Somerled’s grandson Domhnall was the founder of Clan Donald, which became the ruling dynasty of the Lordship of the Isles.

Class Discussion

In what metaphors and terms of reference does the composed of “Baile suthach síth Emhna” describe Raghnall and his qualifications for rule? What is surprising and important about this given the ancestry of Raghnall?

England and Scotland

After the line of Gaelic kings came to an end in 1290 with the death of Margaret, “the Maid of Norway,” the sole surviving descendant of Alexander, Scotland was ruled by a set of elected Guardians. They asked King Edward I of England for advice in choosing between a number of competitors for the Scottish Crown. Edward was determined to become overlord of Scotland. Attempts to resist English domination were defeated and Edward stole the regalia that symbolized Scotland’s identity as a nation, including the Stone of Destiny (aka, Stone of Scone), and took them to England. In 1297 a popular rising aimed at restoring the kingdom was under way. Wallace and Murray were the acknowledged leaders, though it is significant that the MacDuffs, Scotland’s premier native nobility, joined the cause.

Brittany

The Norman invasion had long- reaching consequences for Brittany as well: Bretons were recruited for the forces for William of Normandy and were thus drawn further into French and English affairs. Alan IV “Fergant” was a member of the dynasty of Cornouaille and was made Duke of Brittany in 1084. William of Normandy gave his daughter to Alan in marriage in 1087. She died in 1089 and Alan married the French Ermengarde of Anjou to cement a political alliance.

Alan resigned from power in 1112 and retired to the monastery of Redon; he was the last Breton-speaking Duke of Brittany. Brittany came under the sway of the Plantagenet kings of England (Henry II, Richard, John) from 1158 to 1203, when John murdered the Duke of Brittany, his nephew Arthur. The Bretons responded by aligning themselves with Philip II of France. Arthur’s half-sister married Philip’s kinsman Pierre de Dreux, whose symbol was the ermines which are one of the characteristic symbols of Brittany today.

References

Bannerman, “MacDuff.”

Barrow, “The lost Gàidhealtachd.”

Boardman and Ross, The Exercise.

Day, Conquest.

Foster, Picts.

Gillingham, “The Beginnings.”

Grant and Cheape, Periods.

Houston and Knox, Penguin History.

Jenkins, A Concise History.

Lapidge, “The Welsh-Latin Poetry.”

Leerssen, Mere Irish.

Lynch, Scotland.

Moody and Martin, The Course.

Sellar, “Celtic law.”

Simms, “The Norman Invasion.”

Stiùbhart, Rìoghachd.